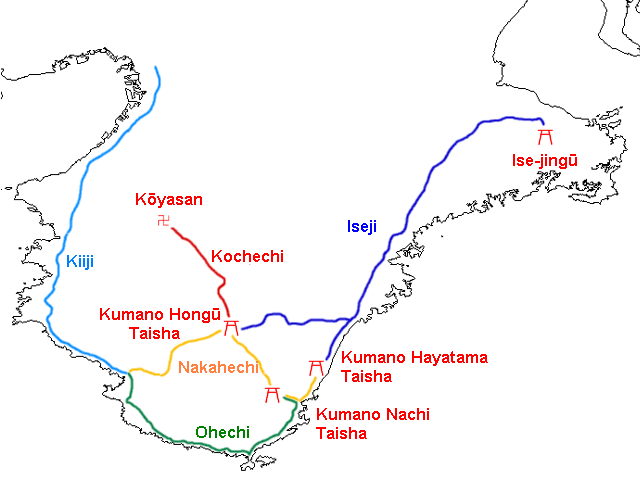

The Kumano Kodo is a series of ancient pilgrimage routes that crisscross the Kii Peninsula (as below), which is south of Kyoto and Osaka. These mountainous trails were and are used to reach the Three Grand Shrines of Kumano, at Hongu, Shingu and Nachi. Shrines of what? Shugendo Buddhism borrowing extensively from and influenced by Shinto and other local forms of animism.

It was the Nakahechi variant (in yellow) where we were going, left to right.

This area has been visited as a site of religious significance by pilgrims seeking healing and salvation for more than 1000 years. More recently it has become a popular walk for tourists, including many Australians and New Zealanders. I’m not 100 percent sure why. It’s not far from Kyoto and Osaka; it is heavily marketed by several dozen companies (who benefit from conveniently located accommodation); and it is a physically-demanding challenge, some of it especially, but not outside the limits of feasibility. All strong reasons, but there are lots of options for walking in Japan which would offer more. That said, a great time was had by all and there was so much to enjoy.

Four and a half days walking after three hours on two trains and half an hour on a bus, gradually getting further and further from the conurbations of the Kansai plain, and marvelling yet again at the genius of Japanese transport engineers as we slid along beside rivers and were swallowed by tunnels.

The first day — for anyone, this is a heavily standardised process; in some cases there is no way of getting off the track end-to-end — was from Takajiri-oji to Takahara. (‘Oji’ literally meaning ‘the younger brother of one’s parent’, but in this case subsidiary shrines pointing the way to the major shrines.)

Clockwise: Takajiri-oji with its torii or gate framing the shrine itself. The bridge which provided access from the bus stop to the information centre and the beginning of the walk which is very well waymaked. A case in point: when it says ‘Start’ that’s what it means. Note the person fishing in the river just to the left of the pole. An engraved stone typical of Shinto shrines, large and small. Among other things. We decrypted one that looked like it might have some particularly cosmic insight and it said this building (a toilet block) was opened by the governor of blah blah prefecture on blah blah date. Shinto adherents believe that natural features are often enlivened by kami, spirits, and that special ones like many of the mountains on the way and the Nachi waterfall have profound powers. A spider, because it was there. A good one though. Tigers’ colours.

Had the smile wiped off my face pretty smartly. ‘Climb steadily through the forest’, the notes say, as they often do. A climb of 350m in a kilometre. Stern. And it was very hot, although not as hot as it had been. But it is a pilgrimage, what do you expect? A bit of pain and suffering might be taken as given.

Clockwise again: One typical version of the track. A lot of it was far more broken and difficult to find footholds than this. Recently tended jizus in a small shrine on the way. Among the endless mysteries of Japanese Buddhism, a jizu is a bodhisattva, a representation maybe of a person who could have reached nirvana but has chosen not to do so that they can help others. Jizus are particularly supportive of mothers who have a child who has died in childbirth, early or stillborn. The oddity was not to see them here, but to wonder at how few there were. When we were walking on Shikoku whole hillsides would be covered in them. Arriving at Takahara (which means ‘plateau’ or high ledge’, we had gained about half a kilometre), passing a gardener at work, the mountainous, and verdant, surrounds, and a lane in the late light.

One of the features of the walk is where you might be staying and what you might eat there. The company we went with, Oku, is very good at choosing interesting minshuku or ryokan, guesthouses of various scale, and Kirin-no-sato at Takahara was an excellent example.

This is our host taking his own version of a selfie. Described by three widely distributed sources as a ‘special Japanese’, he was. Very much the exception to the rule. He sang, he danced or cantered at least, he uncovered the origins of his 20 or so guests and made a cheery little speech about the virtues of internationalism. Then he played flamenco guitar, and not for too long. Below I am pictured pledging my everlasting admiration.

It rained that night. From our bedroom window it looked like this about 5.30am —

and like this at the front door an hour or two later.

It was incredibly humid all day but didn’t rain.

Up past the backyards again — I do like Japanese backyards walks, and there are many of them —

— and into the forest

where we stayed all day. The pictures with Michael and I in them are anomalies. We are not walking through cedar forest. This might be true of 5 percent of the day and provided one of the talking points with comrades of the track. At least one found the monocultural nature of the cedar all about the same age mystifying. He pointed out the absence of bird and animal life (true), the very limited understorey (true) and ground cover (true), and wondered if it could be natural. Sitting in an onsen with him I said I thought at least some appeared to be growing in straight lines about 1.5m apart even though it would mean planting in ridiculous situations on slopes of 70-80 degrees. Subsequently we found obvious evidence of forestry, two harvested coupes in particular on from Jizo-chaya on the last day that looked like they had been subject to intense military bombardment. There were also foresters’ signs up claiming various plots. But is it all like that? Thousands of square kilometres? Could it possibly be? And here, blow me down, just to hand, is the answer I have been looking for. ‘The vast majority of forests are monoculture plantations which were planted to rebuild after the destruction of World War II.’ Planted! When you see the topography of these forests this is simply super-extraordinary. So Ian (son of a Gerrigerrup soldier settler; one for you Ned), we were right.

It also means that there are very few long views but the short views were often quite compelling.

I also notice just now that we climbed another 600m before a 5km descent to get to Chikatsuyu, and that we recorded the absolutely no doubt correct distance of 10.5kms as 14.6. We do tend to wander. Probably just looking where to put our feet.

Chikatsuyu was spread through rice paddies. (Yes, we were down. Proof.) There was even a lookout with a rest area to confirm it.

(Immediately above, this would be Michael checking the race results; and look at her, not even puffing.) ‘During one of the first Imperial pilgrimages here, Emperor Kazan (968-1008) was constructing sutra mounds when he picked two kaya reeds to use as chopsticks. Noticing damp on the red stalk, he inquired whether it was blood or dew. Chi ka tsuya?’ That’s what it says. I’m just passing it on. Oh, and the answer was tsuya. You can relax.

Tonight we would be in the Minshuku Chikatsuyu, prima facie suburban but with an onsen and wonderful food of which this was a small sample.

A typhoon was due the next day, he said casually. Oku have a branch, small but indicative of how much business they do on the Kumano Kodo, in an old tea house in Chikatsuyu. We thought we should consult with a knowledgable person about what our plans should be. The next section could be done at three levels of difficulty by judicious use of buses. He suggested that, given the likely weather, we pursue the easiest option. Even though my wife demurred I thought that sounded terribly wise. Insightful. Even first rate. So … you know. We cheated and took the bus with our friends from Toowoomba and various other pilgrims to Hosshinmon-oji …

where it was pissing down. Furiously. It was an umbrella day, but full of feature and interest and fun. Maybe, just maybe, because it wasn’t so far (supposed to be nearly 8, our instruments said 10.8. Wandering again.), but I think it was the day I enjoyed the most. And it was just the tail of the typhoon. The bigger winds had passed nearby the night before.

It included arriving at Hongu, one of the three Destinations, and how wonderful it was.

‘Cosmic time: Past.’ Quite. And then a few hundred metres out of town at the side of the Kumano River,

was this, the largest torii in Japan …

a gateway to a vacancy which, for whatever reason, moved me profoundly.

As far as I can understand the signs, the temple complex used to be here before it was washed away in some massive floods (I note the levees along the banks of the Kumano now), and it has been left. Vacant. Oyunohara, the place where the foundation deities descended to earth in the form of three moons in the branches of an oak.

Oyunohara, where Yatagarasu, the three-legged crow appears. Yatagarasu, the mark of rebirth and rejuvenation, the creature that has historically cleaned up after great battles, symbolizing renaissance after such tragedies. (The Japanese soccer team wears Yatagarasu on their team uniform, and it is an honoured badge for the winners of the Premiership league to wear for the consequent season.)

This day, the rain had stopped and it was very quiet. The man in the background is a worker picking up rubbish. He would find very little. And it was still. We bought wonderful softu kurema and Michael remembered his stick.

That night we stayed at Yunomineso, a short bus ride away, which describes itself as a ryokan, but one which you would have to say was a long way up market, so far up market that

a) it offered, without asking, a shoe dryer;

b) it provided an illustrated face-to-face lecture with guidebook on how to go about your business there before handing over the keys;

c) it is very close to Yunomine Onsen, a very famous version of that genre (see below) and has its own mineral springs which can be drunk, cooked in, bathed in and which turned my silver ring a bright gold;

d) it has its own indoor and outdoor onsens. Perhaps I should explain. The weary traveller strips off in the dry room, enters the wet room, washes very thoroughly, often sitting on a stool and using a small wooden bucket to contribute. After getting absolutely every vestige of soap off, same enters a large public although gender-separated bath, the onsen, often quite hot, often with mineralised water. The effect is claimed to be restorative, meditative and so on. I usually found them to be too hot and preferred a good scrub under the shower.

e) it does serve a renowned and very fancy kaiseki, the traditional Japanese version of a tasty and tasteful feast. And here it is, but without the river fish.

And here are the instructions and order of consumption supplied to each consumer with additional verbal instruction.

I tussled with the boiled sea snail but found the duck ham on apple very much to my taste. There is a photo of Michael scarfing up the horse sashimi. However, not much for the vegetarian here or often elsewhere in Japan. Myrna ate a lot of rice.

Here’s the river fish.

Don’t eat the head and bones.

Our room. Such comfort really. AND, permitted by both the weather and the building, unconditioned air at last.

We left the next day from Yunomine Onsen, a five-minute drive from our ryokan and a very popular spa town.

Yes. Hot. The bus driver told me that the water bubbling up in the cage behind Myrna was 90 degrees Celsius and I have no reason to disbelieve him. On the basis of visual evidence, it was heavily mineralised.

Ukegawa to Koguchi. We managed to buy some nashi pears at Ukegawa. They are heavy to carry, as big as a handshake and expensive, but they were remarkably refreshing and satisfying for a snack.

It was another day in the forest, distinguished by two things. One was that it was a beautiful day, clear, sunny, mid-20s, comparatively low humidity. The second was that there was a view. One view.

It was a long climb out of Ukegawa’s paddyfields too, 500m up but over five kilometres, steady rather than crippling, and then about half way along this day’s section of the track there is a sharp bend where the trees have been cleared, Hyakken-gura, which looks out over the ‘3,600 peaks of Kumano’. The second photo, from the edge, shows some of the places where logging has occurred recently.

Mr Fit had run ahead and we found him cooling his feet in the river at Koguchi.

Our accomodation that night was Minshuku Momofuku, the building down to the right of this road with the grass in front of it.

It had been a school building with two long single-storey wings joined by an office block.

The river ran past within 20m of our room, a lovely sound, and the windows opened wide. The food was a bit like a school canteen in that you could get what you liked and there was plenty to like. For the first time in several weeks I had cereal and fruit for breakfast.

Probably our favourite accommodation.

And then the final day. Perhaps it is appropriate for a pilgrimage to end with suffering: 14.8 kilometres, all of them difficult. We did end up walking more than 20 that day but there were extra bits at either end.

You start by sneaking in behind a small house with a pale blue (not customary) sign on it to Nachi. After most of an hour we’d done 2 ks. and it wasn’t too bad, in fact it flattened out a bit, and I thought we’ve got this beaten.

The young Belgians who had done the entirety of the third day in the typhoon’s rain came up and offered the idea that it was just up, then across, then down and we were nearly up. Myrna pointed out, correctly, that that was errr never true. But hope springs eternal. Anyway then it got hard, really hard.

I have noted before how hard it is to take a photo of ‘steep’ but at least you can get a bit of idea about the state of the track. You’d get to a corner and think that’ll be it. It’ll ease off. And round the corner there’d be another equivalent stretch, and then another, and then another, and then another … It took a long time to get to the first of four peaks. And then there were three more.

I look a bit done, but I shut my mouth and looked fine.

And of course, it wasn’t flat across the top. It was a constant series of sharp up and downs.

About mid-way this day there is a rest stop (accessible by a narrow road) with a shelter and vending machines. Iced coffee, ah iced coffee, has it ever tasted so good? Had lunch — rice balls, folded omelette, a bit of fish — moved on.

The view below signalled the end of the climbs. Our eventual destination, Kii-Katsuura on the coast, is visible in the background but we were getting there by bus. The temple complex at Nachi was the walking destination.

There was the small matter of getting down.

I usually find it harder than going up and it wasn’t any different this time. The surface varied. Steeper sections were often covered with rocks, sometimes stepped, sometimes flat, at times more slippery than the gravel. I found it quite hard. I think it was quite hard. I’ll say quite hard. The photos peter out around here.

Eventually we stepped out into a parking lot which signalled the edge of the Nachi compound. It had a view which led to the next descent through what I can only assume was a mighty adventure playground: huge slide, dramatic climbing frame, giant swings. And then the next section began. My knees at this stage were beginning to crumple. Steps only for the next 600 metres. I would think literally several thousand. The next sign said ‘500m to Nachi’. We stepped down for 10 minutes or so, signage says ‘450m to Nachi’. Ooo I hate that. I know we’ve gone more than 50m. We’re going down zig-zags which are about 80m long and we’ve done four. It’s a lie. Do it again. Signage says ‘400m to Nachi’. It’s a test. I’ve lost all confidence in advice and just don’t think until Myrna steps out on the first flat bit. There … and there I notice is a comparatively civilised sample of the steps. We are in Nachi.

I’m sure there is some bright witticism one could make about arriving at a temple, the Three-tiered Pagoda no less, and finding that it’s just a photo on building fabric. Does the Wizard of Oz step out perhaps when summoned? At least the Nachi Falls to its right were in honest fettle. Whatever disappointment I felt (negligible) was overtaken by the revelation that we now had to go down another 2-300 steps to get to the bus stop. I’d given over my role of navigator to take up the position of grump and did my best to grimace and moan all the way down.

What would the Buddha say? Probably chuckle and say, ‘Well did you make it or not?’ And I’d have to shut up and say, Yes. Happy in the service. It was memorable, and I’m better for it.

• • • • • • • •

We stayed at Manseiro that night, the six-storey building on the other side of Kii-Katsuura bay: a ryokan with a straight up and down version of the rules with communication via Google Translate. Dinner complex and sophisticated, I have no doubt their very finest work. I’m not sure why the gaikoku hito get parked out of the way by themselves, probably so that their infamies are not widely observed. But we were all a bit tired and I didn’t feel like too much intercultural interaction involving effort. That said, the Manseiro satisfied my two priorities: a load of washing clean and dry, and a comfortable bed. The next day, Kyoto.

Well. Hats off to you and Myrna. What an effort indeed. I think I would have been vegetarian with that meal of snail and raw horse meat. Japanese rice is the best. Oh, and you do win the torii off. Wonderful read, thank you David.

Hi David

Great information and amazing photographs

Hope all is well with you.

Cheers

Douglas Melville.

wow, thanks for sharing. You really are remarkable. Absolutely loved your photos and account. It looks and sounds like a very tough walk. Congratulations

Thanks David! Quite and epic and scenic trip. I’m with you on getting the grumps when it gets too hard – I hope I never, ever have to ascend 350m in 1 km! Your accommodations and the shrines look so charming/full of wonders. I do aspire to hike in Japan one day. I gather this isn’t your first one – I’ll have to pick your brains on that one day.

Love,

Lindy

And not to mention the tedium of hike surfaces which are just too uneven/rocky/gravelly and slippery, particularly when going downhill!

Well done, David, David’s knees, Myrna and Michael. Where did you meet Ian Matheson?

Pingback: The Substrate | mcraeblog