The Border

Yes that’s Uzbekistan. But look more closely at this section of the border with the Kyrgyz Republic.

Yes that’s Uzbekistan. But look more closely at this section of the border with the Kyrgyz Republic.

It’s a crazy puzzle.

Tajikistan, which is mostly the Pamir mountains, makes its claim round a corner to some of the Fergana Valley, manages to include the Kairakum Reservoir and take a skinny bite out of the end of a river valley. But what are those green floaty bits up to?

They are exclaves. You can’t see them all here but there are eight altogether: smallish parcels of land completely surrounded by another country. There is one Tajik and four Uzbek exclaves in Kyrgyzstan, a Tajik exclave in Uzbekistan, and a Kyrgyz exclave in Uzbekistan. Vorukh, where things have turned into shooting match about the route of new road, is another Tajik enclave in Kyrgyzstan. We had to drive right round the Uzbek bulge — all the bulges, large and small — to get to Osh (in Kyrgyzstan but on the border) where we could enter the country.

Political, demographic and civil engineering are not always complementary. Ochre for Uzbeks, red for Tajiks, brown for Kyrgyz. Sort that out. (No one lives where it’s white: mountains or desert.)

Ochre for Uzbeks, red for Tajiks, brown for Kyrgyz. Sort that out. (No one lives where it’s white: mountains or desert.)

Stalin used to shift the borders of the Soviets on a whim, at times to keep them in order or to punish or reward the citizens or more usually his trusties, their bosses. But the breakup of the USSR has left behind a legacy of disputed borders and we were crossing at the site of one of the liveliest disputes.

In 2010 at Osh this became a shooting, burning, killing war between Uzbeks and Kyrgyz who had previously lived reasonably happily cheek by jowl. It doesn’t seem to have been a dispute over territory as it was in 1990 when 80,000 Uzbeks were displaced: just agitation, trouble-making. The effect? More than 2000 buildings destroyed and an uncertain number of lives lost but probably about 50. Errant Tajiks, deposed Kyrgyz leaders, Russian mavericks, even gypsies, were among those blamed along with more obvious targets.

The remnants of these eruptions — shell holes, half destroyed building, bundles of razor wire, serious fences — were all there to see as we crossed the 200m of no man’s land border.

The photo beginning this blog is one of my favourites from the trip, but it is deceptive. Other people in that line-up who had been waiting some hours to cross the border were audibly and visibly cross. When this began to sound like an eruption dozens of military border guards rushed out of their quarters to settle things down. It must be said that it seemed more like an angry game than a declaration of war. But it’s more uneasy than this smile would indicate. Walking that 200m in our tourist bubble was a strange experience.

* * * * * *

Uzbekistan (‘ston’ locally where ‘o’ where we might expect ‘a’ is a common Uzbek linguistic formation, ‘Toshkent’ for example) is just getting over 25 years of rule by Islam Karimov (with Putin at left), an Uzbeki who was appointed as leader by the Russians in 1989 for the very purpose of quelling violent ethnic clashes. When the Supreme Soviet of Uzbekistan reluctantly approved independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Karimov became president of the Republic of Uzbekistan where he sat till 16 months ago when he had a stroke and died.

Uzbekistan (‘ston’ locally where ‘o’ where we might expect ‘a’ is a common Uzbek linguistic formation, ‘Toshkent’ for example) is just getting over 25 years of rule by Islam Karimov (with Putin at left), an Uzbeki who was appointed as leader by the Russians in 1989 for the very purpose of quelling violent ethnic clashes. When the Supreme Soviet of Uzbekistan reluctantly approved independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Karimov became president of the Republic of Uzbekistan where he sat till 16 months ago when he had a stroke and died.

A Soviet loyalist, he was also by nature an isolationist both from other countries and from the vagaries of contemporary life. Being everyone’s stern father doesn’t leave you much room to manoeuvre that way. It is only since the advent of his successor, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, who believes in the economic value at least of tourism, that it has become relatively easy to visit the country.

We were grateful for that. There is a great deal to see in Uzbekistan.

Partly because of the remarkably fertile Fergana Valley, the area of the highest concentration of colour in the map above, 300km long and about 80 wide, along  with the slender strips of fertile green in the arid mountains (see at left for example, out the train window, Adijan to Tashkent), this region has hosted urban civilisations for a long time. Samarkand and Bukhara had been cities for centuries before Alexander the Macedonian conquered them in the 4th century BCE. It was here too that Chinese explorer Zhang Qian sequestered before returning home to make his report on the fertile aspects of Transoxiana, the land between the Amu Darya (in Ancient Greek ‘Oxus’) and Syr Darya, the huge rivers that used to feed the Aral Sea from the Pamirs and the Tian Shan.

with the slender strips of fertile green in the arid mountains (see at left for example, out the train window, Adijan to Tashkent), this region has hosted urban civilisations for a long time. Samarkand and Bukhara had been cities for centuries before Alexander the Macedonian conquered them in the 4th century BCE. It was here too that Chinese explorer Zhang Qian sequestered before returning home to make his report on the fertile aspects of Transoxiana, the land between the Amu Darya (in Ancient Greek ‘Oxus’) and Syr Darya, the huge rivers that used to feed the Aral Sea from the Pamirs and the Tian Shan.

When the Islamists conquered Iran this area became an important site for the maintenance of Persian culture. In 1219 Emperor Chinggis (Gengis Khan), founder of the Mongol Empire, invaded what is now western Uzbekistan. Then in 1369, Timur became the effective ruler and made Samarkand the capital of his future empire.

Amir (King, ‘Emir’, Emirates) Temur is also known as Tamburlaine (as in Marlowe’s play) or Tamerlane which is a derivation from Temur iLeng, or ‘Temur the Lame’. Of Mongol ancestry, he began his adult life as a sheep-rustler and bandit, and was injured in a skirmish which left him lame in his right leg and unable to raise his right arm. But our Uzbek guide Lochin wagged his finger at the use of ‘Tamerlane’ as being disrespectful of a great man, the heart and soul of Uzbek history and connected to a great many of the things that we saw and sites we visited.

Here he is at that very strange place Shahrisabz. ‘The Scourge of God’ ended up with an empire that extended from the Mediterranean to India, famously built on blood and bone. Biographer Justin Marozzi suggests he was responsible for the slaughter of millions — ‘buried alive, cemented into walls, massacred on the battlefield, sliced in two at the waist, trampled to death by horses, beheaded, hanged’. The stories go that at Baghdad he had 90,000 of the inhabitants beheaded so that he could build towers with their skulls. At Sivas in Turkey, where he promised no bloodshed in return for surrender, he had 3,000 prisoners buried alive. His apologists pointed out that he had kept to the letter of the law (if not quite its spirit). Perhaps too symmetrical to be believed in entirety, an absence of the eccentric ribs and splotches that hint at truth-telling — but yes. Not entirely spotless.

‘The Scourge of God’ ended up with an empire that extended from the Mediterranean to India, famously built on blood and bone. Biographer Justin Marozzi suggests he was responsible for the slaughter of millions — ‘buried alive, cemented into walls, massacred on the battlefield, sliced in two at the waist, trampled to death by horses, beheaded, hanged’. The stories go that at Baghdad he had 90,000 of the inhabitants beheaded so that he could build towers with their skulls. At Sivas in Turkey, where he promised no bloodshed in return for surrender, he had 3,000 prisoners buried alive. His apologists pointed out that he had kept to the letter of the law (if not quite its spirit). Perhaps too symmetrical to be believed in entirety, an absence of the eccentric ribs and splotches that hint at truth-telling — but yes. Not entirely spotless.

He was however also responsible for an ambitious building program and a flowering of the arts and science. The evidence is there for that.

Noted astronomer and mathematician Ulugh Beg was his grandson. Beg (which wasn’t his actual name, ‘Ulugh Beg’ means something like ‘big boss’, ‘chief’) built the first ever madrassa (Islamic centre of learning of which there are now hundreds of thousands world-wide) which later became one element of the Registan of Samarkand.

Samarkand, Tashkent and Bukhara were vital and important commercial centres for another several hundred years until their influence and buoyancy dissipated via the combined impact of feuding Uzbek Khanates (kingdoms, three of them spread along the Silk Roads from the Kyrgyz border: Kokand, Bukhara and Kiva) and competition from the trade routes established by sea.

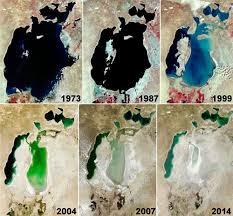

Uzbekistan is also famous for being the site of one of the most well defined ecological disasters of modern life. This one. The Aral Sea, 1973-2014. 40 years. Once a huge body of water abundant with life, it is now almost extinct with all sorts of knock-on consequences for those living in the region. Sandstorms for example. Appalling. So bad it is now a tourist ‘attraction’.

The Aral Sea, 1973-2014. 40 years. Once a huge body of water abundant with life, it is now almost extinct with all sorts of knock-on consequences for those living in the region. Sandstorms for example. Appalling. So bad it is now a tourist ‘attraction’.

What happened? Beginning in the 1960s plantings in the Fergana Valley which had supplied food for hundreds of thousands of its inhabitants for millennia were switched over 20 or so years at Moscow’s behest from food to cotton. This policy converted almost the entire agricultural economy of Uzbekistan to cotton production. It is now an embarrassment to mention the fact that in the national interest each year at harvest families were relocated, factories shut and schools closed to provide a workforce to pick the crop. There are still vestiges of this phenomenon in public decoration. One of Tashkent’s underground stations, I think Bobur, is decorated with wall panels of stylised cotton buds and hordes of pickers. We still saw cotton plantings but they were interspaced with a wide range of other crops. Sandalwood, for example, was quite widely in evidence. Cotton production has gone from 10m. tonnes (its peak, and the largest producer in the world) to 3m. tonnes last year.

But the ecological issue was far more profound than the cultural one. The Aral Sea’s two main tributaries were the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya. Water from the Amu rarely flows into the Sea any more and from the Syr never. It has been diverted by irrigation plans and methods of the lowest imaginable quality. There is a high level of awareness of this issue but since the breakup of the Union of Soviets no money to do anything about it.

But the ecological issue was far more profound than the cultural one. The Aral Sea’s two main tributaries were the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya. Water from the Amu rarely flows into the Sea any more and from the Syr never. It has been diverted by irrigation plans and methods of the lowest imaginable quality. There is a high level of awareness of this issue but since the breakup of the Union of Soviets no money to do anything about it.

* * * * * *

Andijan

It took us about an hour to get across the border, a haphazard affair, but seemingly with officials going out of their way to be both pleasant and helpful — to us anyway.

Our first destination was the bank to acquire piles of sum, 5970 to the AUD. We saw one man filling four cardboard cartons with stacks of high denomination notes and heading off with them on a hand truck. It was suggested he was going to buy a car. I had no plans to buy a car, but it was quite hard to work out how much money to change. This lump of 5000s I thought might last a week but I spent it in three days.

I had no plans to buy a car, but it was quite hard to work out how much money to change. This lump of 5000s I thought might last a week but I spent it in three days.

Things had changed. The country had a different feel. This could have been Kyrgyzstan.

But this probably couldn’t. Just to the left was a massive market with very large patriotic urgings on its walls. The building to the right and the tops of those on the left are probably government housing.

Just to the left was a massive market with very large patriotic urgings on its walls. The building to the right and the tops of those on the left are probably government housing. Less Russian, more Persian. We were coming to some of the most wonderful examples of Muslim architecture and decorative art in the world. This panel above was perhaps 1/20th of the decoration on the ceiling of one of the deep verandas which were often present in older buildings. Almost always decorated richly enough to give you pause and to wonder how it had been done, and how it had been maintained.

Less Russian, more Persian. We were coming to some of the most wonderful examples of Muslim architecture and decorative art in the world. This panel above was perhaps 1/20th of the decoration on the ceiling of one of the deep verandas which were often present in older buildings. Almost always decorated richly enough to give you pause and to wonder how it had been done, and how it had been maintained. This stone mural was the best feature of Andijan’s museum, a sad dark place with, inter alia, a large collection of representational paintings which were ugly, poorly crafted full of muddy colours and badly presented. We went there while we were waiting for our train to Tashkent. One day it may be full of wonders but it was a slightly punishing experience as we tried to be polite listening to a long dull explanation of each of the exhibits which was then translated. Hard work. I was also hungry and tired. We slid out of range. The hunger issue was resolved by eating in a cafeteria, a meal for which I had high hopes

This stone mural was the best feature of Andijan’s museum, a sad dark place with, inter alia, a large collection of representational paintings which were ugly, poorly crafted full of muddy colours and badly presented. We went there while we were waiting for our train to Tashkent. One day it may be full of wonders but it was a slightly punishing experience as we tried to be polite listening to a long dull explanation of each of the exhibits which was then translated. Hard work. I was also hungry and tired. We slid out of range. The hunger issue was resolved by eating in a cafeteria, a meal for which I had high hopes and which ended up doing me and my exhaust system in for several days. Tasted good though.

and which ended up doing me and my exhaust system in for several days. Tasted good though.

We visited a super market and climbed aboard for the slightly eccentric train trip to Tashkent. ‘Eccentric’ in the sense of its complex changes in direction and speed, slooooooowwww then FAST, but also what we were looking at out the steamed-up windows. There’s a photo above. Arid hills creased with a sliver of green, snowy peaks over to the south — a mixed economy. At least some of those green slivers were mining towns, because unlike KR Uzbekistan has got a number of things in its ground that people want, not least oil and natural gas. There is some money here, possibly plenty, but culturally it still seemed to be struggling for confidence, settling its priorities and getting over Big Daddy. They leave a deep mark those men.

Tashkent

('Stone City', suggestive of indomitability)

Hmmm. Good one. That map tells you absolutely nothing, doesn’t it. Tashkent is in the eastern end of Uzbekistan, one of four regions with, spreading west, Samarkand, Bukhara and Kiva being the other population centres.

2.5 million people, one of the big cities of Central Asia, damaged by an earthquake on 24 April 1966. ‘Massive destruction’ is the term used, with 85 percent of the city’s buildings destroyed including the majority of the old city and its landmark structures. But the brave citizens said no, we will not be daunted. Heroic style. Signified by, we were told, a much loved monument (which I note, says 26 April. I’ll leave it with you.)

The earthquake had several effects. One was to produce a monument to Soviet town planning and architecture. Wide boulevards, massive plantings, grandiose buildings and a staggering amount of white marble. This is just a small section of the central ‘park’ area named after Temur who has pride of place in the middle, with our fascinatingly sub-grand hotel in the photo below as a backdrop. The hotel was representative of vast aspirations which had not worn well, but it did have a very interesting and diverse clientele: a genuine gathering of nations. You’d stay there for that reason alone.

This is just a small section of the central ‘park’ area named after Temur who has pride of place in the middle, with our fascinatingly sub-grand hotel in the photo below as a backdrop. The hotel was representative of vast aspirations which had not worn well, but it did have a very interesting and diverse clientele: a genuine gathering of nations. You’d stay there for that reason alone.

At night. And, yes, the whole vast wall of the hotel becomes a screen. (I don’t know what impact this had on people whose rooms were on this side. We looked outwards to the back.) A lot about Tashkent, now, says modern, today, up to date — and also, look how modern, today and up to date we are. Down the street the shops were good and interesting, full of course with China’s produce, shopkeepers were friendly. The eateries at night looked great, packed with people having a good time.

And, yes, the whole vast wall of the hotel becomes a screen. (I don’t know what impact this had on people whose rooms were on this side. We looked outwards to the back.) A lot about Tashkent, now, says modern, today, up to date — and also, look how modern, today and up to date we are. Down the street the shops were good and interesting, full of course with China’s produce, shopkeepers were friendly. The eateries at night looked great, packed with people having a good time.

Our first port of call was to …. how do I express this? one of the original copies of the first Koran. That might be right. It looked like it had been constructed out of some gelatinous substance (deerskin actually) and had BIG WRITING and you couldn’t take photos.

Let’s see if I can find one. Bingo.

Let’s see if I can find one. Bingo.

I believe there are five of these in existence. One here and one (of which there are no photographs) in the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, one in the British Museum I think. But it’s all shrouded in thick fog as such things tend to be. With hindsight I can appreciate why Lochin wanted us to see this early in his guidance. From some points of view it is a gigantic experience to have seen this. I hadn’t at the time been sufficiently enculturated.

The building housing this, many other versions of the Koran and other sacred and learned documents was the madrassa Muyi Mubarak, the ‘sacred hair (of Mohammed)’, a strand of which may or may not be included inside. It is in Khast Imam Square which provided our first view of the interior of a mosque, from my earthbound perspective a vision of vacancy, stillness. Outside it was another story. Islamic decoration. Incomparable. Simply breath-taking. Maths run wild!

Outside it was another story. Islamic decoration. Incomparable. Simply breath-taking. Maths run wild!

Tourists don’t usually come to this square, a nondescript affair really. But they do go on the underground, a source of great civic pride: three lines, 40km, 29 stations, c. 180,000 daily rides and glorious decoration. (Melbourne’s underground: 12 km.; Geelong’s: 0)

And even if not so many other people do, they go to the market, Chorsu Market.

The market! Ah Lord. I customarily resist markets unless I want to buy something.

The market! Ah Lord. I customarily resist markets unless I want to buy something.

We needed coffee. No coffee shops so the horsemeat salesman organised his wife to provide us with two cups which cost us exactly nothing. Mmmm what sort do you think? Turkish? Uzbeki? Russian maybe? No. ‘Labros’, the local brand of instant. There she is getting the hot water out of the urn, and you’ve found our hiding place (where we were able to sit down).

Then to get into the spirit of things we thought we might buy some nuts and dried fruit. Looked good, the samples tasted good and the sparkly-eyed young man on the right was eager to sell us some. When you go, keep an eye out for him. He put modest amounts of things we didn’t especially want into ziplock bags and then, holding our money, suggested the price was 150,000 sum. 25 bucks! We hadn’t bought anything for $25! It’s what happens when you get over-excited about yourself, and forget that foreigners might be soft touches but they aren’t complete morons. The female foreigner instituted direct action, snatched the money out of his hands, returned the produce and no transaction was recorded. Markets. Plloooffff.

When you go, keep an eye out for him. He put modest amounts of things we didn’t especially want into ziplock bags and then, holding our money, suggested the price was 150,000 sum. 25 bucks! We hadn’t bought anything for $25! It’s what happens when you get over-excited about yourself, and forget that foreigners might be soft touches but they aren’t complete morons. The female foreigner instituted direct action, snatched the money out of his hands, returned the produce and no transaction was recorded. Markets. Plloooffff.

It went on. Flea market: hats, scarves, clothes, books, bits of remnant engineering. God it went on. Jacob bought a glass vodka dispenser in the shape of a fish. He may not have been able to do that elsewhere.

Hot, tired, hungry, lunch was at an establishment which was an interesting combination of a KFC and a high class cafeteria prodigiously swollen with staff.

And then the museum. My hunger had been replaced by treacherously loose bowels, and I wasn’t perfectly set up to enjoy civic landmarks. It could have been very good especially the third floor which provided a very sanguine and optimistic picture of Uzbekistan Today (as well as an unreconstructed paean to the late Mr Karimov). I learnt that of the 100 national Parliamentarians, constitutionally 15 must be from the environment movement. Not quite sure how that would work out in practice, but an excellent gesture at least. I learnt there was a good deal of angst about the fate of the Aral Sea. I learnt that there were major chemical and mineral industries in Uzbekistan and that this ‘impoverished’, second-and-a-half world country can sustain a substantial car manufacturing industry (GM Chevrolet, Daewoo, MAN trucks and SAZ buses) whereas Australia can’t.

We got back to our hotel to find members of another Intrepid tour who raved about several art galleries and design museums they had seen and incidentally that there was an opera house with a very full schedule of programs. Well! Let’s go baby! Opera in Tashkent, what a delectable prospect.

Tonight’s program: ‘The Demon’ by Anton Rubinstein, libretto based on a poem by Lermontov, sung in Russian. A deep expression of Russian Orthodox Christianity written by a Russian Jew on stage in a Muslim country. What could be more appropriate?

It is not often performed for reasons which may become apparent by reference to this summary of the libretto.

Demon sees and falls in love with the lovely Tamara who is awaiting her wedding to Prince Sinodal. Tamara is fascinated but frightened. [an old story] The Prince’s caravan, making its way along the Silk Roads for his wedding, is delayed by a landslide. Demon organises Tatar attack during which the Prince is mortally wounded.

Sinodal’s body is delivered to the wedding preparations. Tamara is overcome by grief, but to her horror, keeps hearing the supernatural voice of the Demon. She begs her father to let her enter a convent. Demon intends to enter same convent believing that his love for her has opened his spirit to goodness. [! Yeah sure.] An Angel tries in vain to stop him.

Tamara prays in her convent cell but is constantly troubled by thoughts of the Demon, who appears to her in her dreams. Demon now appears in reality, declares his love for her and begs her to love him in return. Tamara tries to resist her attraction to him but [of course, it’s the Bad Boy yarn] fails. Demon kisses her in triumph. The Angel suddenly appears and shows her the ghost of Prince Sinodal. In horror, Tamara struggles out of the Demon’s arms and falls dead. [And let that be a warning to all you young ….]

The Angel proclaims that Tamara has been redeemed by her suffering [phew], while Demon [hiss] is damned to eternal solitude. The Demon curses his fate. In the final apotheosis Tamara’s soul is carried to Heaven accompanied by angels — as sung by a huge chorus of women standing round the arc of the third floor, a sublime finale.

Mmmm … how to interpret this? Should we call in Dr Freud? Or is the question of interpretation utterly superfluous? That might explain why the guy sitting next to me had a conversation on his mobile phone during the second act.

The Opera House, half full that night, had recently been refurbished and was lovely. The cast was most capable, except for the chap whose magnificent mane played the Demon and whose family, friends and groupies comprised the front few rows. The chorus was magnificent and Tamara had a powerful and lilting soprano. A wonderful 60,000 sum worth ($A12.00). Tosca was going to be on the night we returned to Tashkent. What a feast that could have been.

The Opera House, half full that night, had recently been refurbished and was lovely. The cast was most capable, except for the chap whose magnificent mane played the Demon and whose family, friends and groupies comprised the front few rows. The chorus was magnificent and Tamara had a powerful and lilting soprano. A wonderful 60,000 sum worth ($A12.00). Tosca was going to be on the night we returned to Tashkent. What a feast that could have been.

We walked back to the hotel with ice creams through a dulcet night to find Croatia mashing Argentina 3-0.

We weren’t in Tashkent long enough. That’s my summation. It looked fabulous but was always just a smidgen out of reach because we were hostage to THE PROGRAM. The one where TP dominates all else. The one where you get monotonous lectures in heavily-accented English about not much. The one where when you get hungry or need a cup of tea you just have to shut up and wait because it’s not the next thing on the list. The one where you just have to assume ‘it will all turn out for the best’.

On reflection I realise that Lochin really wanted to show us his version of the absolute best of his country and it was a collection of very fine choices, and he really did give us a very great deal including a splendid and sensitive insight into the Uzbek practice of Islam. In fact I have written here: ‘so well prepared, knowledgable, quiveringly sensitive, a perfect host, obviously powerful figure in the tourism community’ (as well as several times National Judo Champion of Uzbekistan), but. BUT. A standard pedagogical problem: you might have a purpose and a brilliant plan and resources, but you’ve got to be responsive to your class. That old ‘zone of proximal development’. I’ve written about this issue elsewhere.

I’d go back tomorrow. I should.

But let us keep MOVING FORWARDS … There is so much still to see!!