Walking down the 99 steps that lead from the entry to MONA (David Walsh’s Museum of Old and New Art in Hobart) to its very own wharf, I couldn’t do other than try to work out why, yet again, the experience had had such an impact on me.

Walking down the 99 steps that lead from the entry to MONA (David Walsh’s Museum of Old and New Art in Hobart) to its very own wharf, I couldn’t do other than try to work out why, yet again, the experience had had such an impact on me.

The ferry ride is certainly part of the preparation.  You might see, for example, Sea Shepherd’s ‘Bob Barker’ (Art? quite possibly.).

You might see, for example, Sea Shepherd’s ‘Bob Barker’ (Art? quite possibly.).  You will see the interstices of Pasminco’s smelter at Risdon. And apart from any of that, it’s a ride up the Derwent Estuary which is long enough to become slightly intoxicated by the scenery, short enough not to stale expectation or redirect interest.

You will see the interstices of Pasminco’s smelter at Risdon. And apart from any of that, it’s a ride up the Derwent Estuary which is long enough to become slightly intoxicated by the scenery, short enough not to stale expectation or redirect interest.  Near the top of the stairs is the rusting cement truck that isn’t a cement truck but lacework with a vaguely subcontinental feel. It’s near the tennis court and the polished stainless steel crazy mirrors cladding the exterior of the foyer. And the carpark designated for ‘God’ next to the one for ‘God’s mistress’ (now wife).

Near the top of the stairs is the rusting cement truck that isn’t a cement truck but lacework with a vaguely subcontinental feel. It’s near the tennis court and the polished stainless steel crazy mirrors cladding the exterior of the foyer. And the carpark designated for ‘God’ next to the one for ‘God’s mistress’ (now wife).  Strangers pay; Tasmanians get in for free. So far so wacky. Fun. A hook. Happily sucked in to date. What’s next?

Strangers pay; Tasmanians get in for free. So far so wacky. Fun. A hook. Happily sucked in to date. What’s next?

This is already chewing away at your expectations of what the experience of art — the gallery experience of art, the experience of gallery art — should be, SHOULD be. (Just beyond the corner of your eye you can see Nonda (architect) or Nicole (curator for Australian art) or Olivier (for international art, both in the pic) ringing David (creator, funder and muse)

This is already chewing away at your expectations of what the experience of art — the gallery experience of art, the experience of gallery art — should be, SHOULD be. (Just beyond the corner of your eye you can see Nonda (architect) or Nicole (curator for Australian art) or Olivier (for international art, both in the pic) ringing David (creator, funder and muse)  and saying: hey, you know what we could do? When they … blah blah blah and then they … how about …? And David saying: Yeah yeah great great. And then you could … blah blah blah… ? And it happens. Is that the art? The profusion of realised ideas?)

and saying: hey, you know what we could do? When they … blah blah blah and then they … how about …? And David saying: Yeah yeah great great. And then you could … blah blah blah… ? And it happens. Is that the art? The profusion of realised ideas?)

Then there is the literal immersion among the cliffs of sandstone. You are firmly in the heart of the Berriedale peninsula and there are no distractions apart from the artworks in which I include the building. The sandstone is part of the aesthetic experience, as managed and considered as any of the other works. In fact I like this pic with its mix of natural and constructed orders as much as I do any of the other photos I have taken there. [

[ A footnote. The Guggenheim at Bilbao is also a truly remarkable building but it overpowers everything inside it except Richard Serra’s ‘Snake’, three vast curved and aligned sheets of rusted steel perhaps 30 metres long and 4 metres high. If you wrote about it and didn’t use the word ‘sinuous’ you would be fired. And in this case you measure quality by weight. Considerable. Everything else? Negligible. The Guggenheim in New York, another famously distinctive art building is, with its canted floors and functionally-speaking, just a nuisance.]

A footnote. The Guggenheim at Bilbao is also a truly remarkable building but it overpowers everything inside it except Richard Serra’s ‘Snake’, three vast curved and aligned sheets of rusted steel perhaps 30 metres long and 4 metres high. If you wrote about it and didn’t use the word ‘sinuous’ you would be fired. And in this case you measure quality by weight. Considerable. Everything else? Negligible. The Guggenheim in New York, another famously distinctive art building is, with its canted floors and functionally-speaking, just a nuisance.]

At MONA you are inside, captive to the experience. You’re not going anywhere quickly (as you might for example inject yourself with an hour of classic Australian in the top floor galleries at Fed Square, or a dedicated trip to the netsuke and their accompaniments in Sydney). That noted, how strange it is that the usual art fatigue/satiation takes so much longer to kick in.

During this last visit the first sensation was the chiming of bells generated by guest trampoliners. Yes quite. Trampoliners. The trampoline had replaced the intermittent spurts of water lit to notify us of the most Googled headlines of the day.

About this Mr Walsh writes on the iPod-like ‘O’s which provide (considerably more than) a guide to what is in MONA.

We wanted to be brave. We wanted to show that, unlike traditional public museums, we were not running a popularity contest. We wanted to show that we didn’t need ‘destination art’. So just before we opened I imprudently said, ‘If a work is “loved” too much, I’ll take it down.’ That’s about as silly as Opus Dei Catholics wearing a cilice, or deliberately picking up the ugliest boy or girl at the nightclub.

But I go in for a bit of self-flagellation occasionally. I know that we humans are machines that improve from the impact of stressors. Muscles that work hard become harder-working muscles. And I subscribe to that perspicacious platitude, ‘Whatever doesn’t kill you only makes you stronger’, independently invented by those two great philosophers of the human condition, Frederick Nietzsche and Kelly Clarkson. So now, we’ve taken down bit.fall (loved by 114,938 at the time of writing), and we’ve taken down [Sidney Nolan’s gigantic] Snake (loved by 56,787). And we replaced them with a trampoline and a movie. Let’s hope you love trampolines and movies. But I think nearly everyone loves trampolines and movies.

Nearby was the pick-pock of table tennis played on a deeply creviced table and another covered by ‘art’. (Why? Why not.)  I seized the handles of the machine designed to record my pulse and send it pumping through pairs of large light bulbs along with hundreds of others on a most orderly voyage to oblivion. For someone inclined towards atrial fibrillation I got an inspiring response, regular and strong. The cloaca machine was making its olfactory presence felt; and David, if you’re there, it’s becoming intrusive. Happy to have a shit factory in one corner of an art museum but not for it to dominate the whole show. OK? The other miracles of human ingenuity present suggest that you can probably sort this small problem out.

I seized the handles of the machine designed to record my pulse and send it pumping through pairs of large light bulbs along with hundreds of others on a most orderly voyage to oblivion. For someone inclined towards atrial fibrillation I got an inspiring response, regular and strong. The cloaca machine was making its olfactory presence felt; and David, if you’re there, it’s becoming intrusive. Happy to have a shit factory in one corner of an art museum but not for it to dominate the whole show. OK? The other miracles of human ingenuity present suggest that you can probably sort this small problem out.

I began doing all the same things I did last time but better. I was going to duck past the ‘When my heart stops beating’ cabinets but was waylaid and absorbed for the best part of twenty minutes and could have stayed longer. I listened to all the music tagged on to the videos in the red room (and went back later to listen to some of the songs again). I found new images and ideas in Juan Davila’s Burke and Wills ‘The Arse End of the World’.  The mummified cat’s head transfixed me again. In the process of checking what else was around here I examined the chocolate cast of the terrorist’s body parts with more care because this part of the gallery/museum/building — its displays as far as I know more stable than in other sections — has begun metastasizing in the best possible sense.

The mummified cat’s head transfixed me again. In the process of checking what else was around here I examined the chocolate cast of the terrorist’s body parts with more care because this part of the gallery/museum/building — its displays as far as I know more stable than in other sections — has begun metastasizing in the best possible sense.

There are thick gestalt undercurrents of sensation, speculation and meaning at work here — every curator’s wet dream realised.

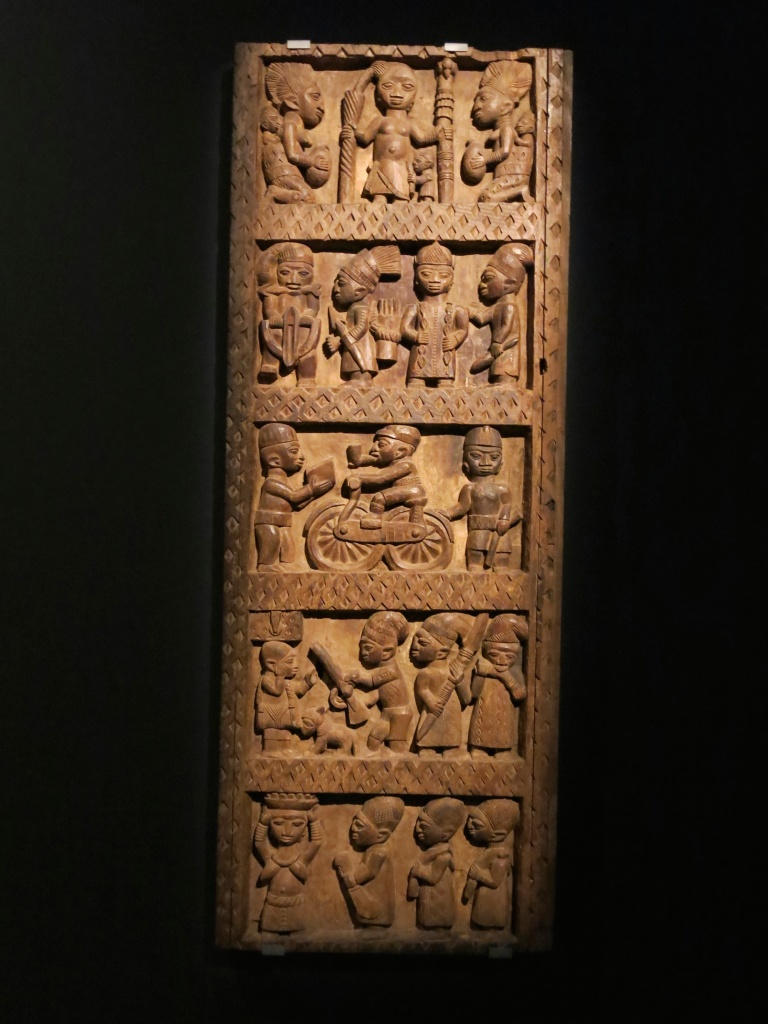

Escaping, I got caught up in watching Leni Riefenstahl’s ‘Olympia’, her film of the 1936 Olympic Games. Years ago I saw ‘Triumph of the Will’, but this was something different and just as addictive. Perhaps it’s hard to muck up films of peak sporting moments. But her astonishing craft was on open display. (Am I still talking about art here? Have I been at all? Are these just stimulating curiosities?)  And I spent quite some time looking at this door, ‘the first work David bought – way before he thought of building MONA. David bought this from a gallery in South Africa because he had too much money to take out of the country.’

And I spent quite some time looking at this door, ‘the first work David bought – way before he thought of building MONA. David bought this from a gallery in South Africa because he had too much money to take out of the country.’

I do like this door. The closer you look the more puzzling it becomes. What’s going on in that top panel for example? Footballers worshipping goal posts? Samson pulling down the temple pillars? But there is that child at foot who could be crying. And then there is the bike. Such a dominant position in the whole, and the pipe … what’s that about? If I’d had 18,000 pounds I had to get rid of and this was at hand I would have bought it too.

What did the ‘O’ say? The O is the guide that everyone wears around their necks. There are no labels or explanations on the works so there’s a strong incentive to use the O. This is such a clever place.

I’m not keen on guides as a rule, nor explanatory statements attached to artworks (especially if they are written by the artist. One could almost generalise and say visual artists should never under any circumstances be allowed to write anything down, at least about art and especially their own. Except you Helen, of course.) But what you get at MONA is of a different order. There are people there who can write for a start; several people, including the boss. And material filed under ‘Artwank’ is a lot less artwanky than most such and almost always contains information that you’d like to know. So …

WHAT IS THIS DOOR?

This elaborate carved door is one of many made for palaces in the region of Osi-Ilorin, an Opin village in northeast Yoruba (now part of Nigeria). Such carved doors were one of the marks of kingship for the Yoruba people. Working in the first half of the twentieth century, Areogun evolved a distinct style of his own, combining elements from centuries-old Yoruba tradition with contemporary motifs on the themes of royalty, law and order.

Areogun’s name — The artist’s birth name was Dada, the name given to people born with curly hair. Areogun, as he was known in his lifetime, was his oriki, or praise name: the local dialect version of a ri owo gun, meaning ‘he sees money [through] iron’. His son, George Bandele, began to use the standard Yoruba form, Arowogun, in later years.

Areogun’s workshop — Many carvings from Areogun’s workshop or atelier would have been identified with his name and it is rarely possible to attribute them to specific hands (he had four apprentices in the 1940s). Doors from his workshop, exhibited in London at the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley in 1924, are now in the British Museum.

Yoruba culture — Yoruba cultural heritage now extends to an estimated 25 million people of Yoruba descent in other parts of Africa and the Americas – including Brazil, Cuba, Trinidad, Haiti, and the USA – as a consequence of the Atlantic slave trade and diaspora of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

I’m pleased to know those things and I’m pleased to have them at hand when I’m looking at the piece rather than when I get home or am down the street with Dr Google. It builds the picture and fills out the detail in ways I appreciate.

Click on ‘Gonzo’ and what do we find?

Why do artists make art works?

This is a Nigerian Palace door made by Aerogun. You already knew that, it says so on the front page. But what does it mean? Why did he make it? He clearly had a flirtatious interest in the West, and his unsteerable, downhill bicycle must at least be a joke, perhaps a metaphor.

[And so you check the bicycle and yes, you see what the writer (Walsh) means. If it matters, yes, it will not turn. You missed that the first time. How closely were you looking?]

Presumably he was ordered to make it, but did he make it for the one who gave the order, or did he make it for himself? If for himself, and I think it’s always a bit for himself, presumably the motive was an assemblage of: pride in craftsmanship, need for self-expression, love of status, an urge to serve and maybe even a fear of the consequences of failure.

[Hmm yes. Why do people make art? It’s such hard work generally with so little public pay off. I read today about the 8 million unique music tracks sold on iTunes in 2011: 102 tracks sold more than a million units each, but 94 percent sold fewer than 100 units. One-third sold one unit each. Does that matter? It doesn’t seem to discourage artists, potential or active. If no one read this blog, would I care? Would it make the experience different? Are there some members of the potential audience I am counting on more than others? Will one special reader make it worthwhile? Five? And why sit by yourself in a room researching, thinking and writing? Isn’t that faintly neurotic? And isn’t the point that you want to get something straight in your own mind and plodding through revision after revision is the only way you know how to do that? Isn’t that sort of sad, and incompetent? If you can make something not so much beautiful as well-crafted so much the better. Something that will satisfy and interest someone else. Something that reeks of ease and simplicity … And do you fear failure? Of course. Although you will probably be happy to define what failure is yourself.]

These are the proximate motives but what generates them? Is the capacity of biology to reproduce genetically selected talent on display here? He’s clearly good. All it takes is: good having a bit to do with biology; good being a bit sexy; good not getting in the way of making kids; and some generations. I guess I’m saying all the reasons he does stuff were real to him, but there is stuff that is real to everyone. Do all artists, whether tribal or western, antiquarian or contemporary, concrete or conceptual have the same fundamental motives? I think so. That goes for most people from most fields of endeavour, I think.

[See you can understand this. You could talk about this at lunch or even at the footy if you were keen enough. It’s unconstipated, direct, all meat with quite a lot of rather piquant sauce.]

Culture hides this stuff, but it keeps rippling through. I collect it. Does that make me a bit more sexy? I bloody hope so. I’m grasping at straws here.

[The honesty (real or artificial, I don’t care) which — perhaps admiring the courage, the insouciance of the author — makes you want to go back for more.]

But this is all a serious matter. The first time we went to MONA the special exhibition was ‘Theatre of the World’. This time it was ‘Red Queen’. I paid no attention to this whatsoever. I wasn’t required to. I didn’t see signs. There wasn’t a ‘Red Queen’ room set aside. It would have added another layer of complexity to what was already too much to absorb. I saw lots of other things. I spent quite a while looking at Arthur Boyd’s ‘Melbourne Burning’ for example. As a rule I am not drawn to Arthur Boyd, but here is a Boyd with a significant wrinkle that makes you wrestle with it further, not ‘just a painting’ or ‘just art’ (what’s with this Melbourne burning business? He’s not a realist), but reaching out to you with another cognitive demand.

This is one of the important factors that makes what is in MONA so interesting.

I noticed, but barely, a couple of lonely looking Kimberley paintings tucked away in a corridor. Probably Rover Thomas, and probably masterpieces if I’d looked at them carefully, but I strolled past without looking at them. In other galleries they would be taking carefully lit central space. (MONA is not alone in this regard. In the Louvre people run past two very fine Caravaggios, one of which is ‘Death of the Virgin’, a very rare subject, to join the impenetrable crowd in front of the Mona Lisa. ‘Smaller than I thought it would be.’ ‘Did you get a photo?’ ‘That’s bullet proof glass over it you know?’ ‘Yeah. Amazing isn’t it.’ Just a digression.)

I spent most time watching 30 TV screens (6 x 5 on a wall) each with a person singing along a capella (‘in the chapel’, unaccompanied, they’re singing along to their headphones) with Madonna’s ‘Immaculate Collection’. Just wonderful. Giving it their uninhibited all. The attractive girl second column second bottom had a neat seemingly unconscious shtick which never missed a beat. Most of them had something going on but she had it all. Someone, one of the guys in the top right hand corner, was singing flat. I say that without prejudice. And is that art? I think I have to say, I mostly don’t care; but if I did have to care I would almost definitely say yes. As I’ve gone back over not just the things I saw but the things I missed I’ve come to appreciate what the Red Queen might have been. It is built around the issue of art as an evolutionary adaptation, and what a good question.

Why does art and art practice survive? Why don’t Andre Rieu and Hallmark Cards define its boundaries?

I did look at Balint Zsako’s water colours again (wonderful) and tried to confront but was overwhelmed by Henry Darger’s Vivian Girls. I was also absorbed by the work of the Rabus brothers. Swiss. Why haven’t I seen their work elsewhere? Does David Walsh sit at the end of the production process buying the lot? Here’s ‘Neige et Renard’ (Snow and Fox). On your O you may listen to the artist yodelling (formidably) if you wish but here is what Tweedledum has written about it.

On your O you may listen to the artist yodelling (formidably) if you wish but here is what Tweedledum has written about it.

Leopold Rabus dabbles in the realm of fairy tale and fantasy but, crucially, there is an inner coherence – a kind of madman’s logic, if you’ll pardon my hyperbole – to the worlds he presents us with. This has something to do with the strange-but-familiar forms he depicts, and a lot to do with his mastery of the genre he is using: painting. He constructs his generic outlines with reverence and skill, and then imaginatively and expressively colours them in. I don’t mean that he actually does this, literally, in this order. What I mean is that he is, consciously or otherwise, striking a rather sumptuous balance between creative innovation (his works are distinctively his; you can sense just from looking that he is expressing something natural to him) and reverence to the tradition he is working with. In other words, the boy can paint. My eye is spectacularly untrained but still, to me, his stuff just looks right, pulls together without any seams poking through, and at the same time is disorientating and intriguingly difficult to decipher.

You may have noticed by now that in this exhibition, The Red Queen, we are starting to consider the arts as an evolutionary adaptation. An adaptation is a trait modified by natural selection that improves the individual’s chances of surviving and procreating. … In order for art-making to be established as an adaptation, a number of criteria have to be satisfied. Most importantly: how or why might the trait confer some sort of advantage over others who lack it? There are a number of possible answers to this. In brute sum: art-making enhances sexual status and attractiveness; or it coheres and unifies individuals so they are better placed to thrive as a social group; or it isn’t an adaptation, it’s a by-product of other related ones. And finally, perhaps the arts allow individuals to exercise and develop their flexibly abstract social imaginations, so that they are better placed to walk that tightrope – so important to our hyper-social species – between competition and co-operation? Keeping this last point in mind, consider again Leopold Rabus’ creative ingenuity.

Brian Boyd, one key proponent of the ‘flexibly abstract’ theory of the arts as adaptation, explains in his book On the Origin of Stories the need for artists of all kinds to strike a balance between innovation and tradition. From an evolutionary perspective, economy is key: the ‘cost’ of a behaviour (in energy use or exposure to illness or danger) must be more than cancelled out by its benefits (increased social status or access to attractive mates, for instance). That is one reason why we do not re-invent new genres each time we write a poem or a book, or paint a painting or compose a symphony. Such extreme acts of creativity are too costly to be sustained. Observing and imitating established artist forms – such as the fairy tale, or the use of perspective in painting – ‘reduce invention costs by posing well-defined problems and offering partial solutions’. At the heart of creativity, therefore, lies the ability to build on what came before – but, crucially, to twist it, or pervert it, or thwart or react to it in some new way, in order to retain the attention of your audience. ‘We appreciate,’ says Boyd, ‘even minor variations within established forms as worthy of attention and repose. With our senses highly tuned to basic patterns, we enjoy repetitions and variations on a theme in art as in play’. This is one way to look at this painting.

And indeed it is. But this is serious discussion. This is a very thoughtful idea thrown in from left field. But what a good one, thickening out the whole experience.

I’ve read press articles about MONA and there are two stories: 1) David Walsh; and 2) the shocking stuff in this gorgeous gallery. That’s it. Two roads diverge on the latter matter: shocking delight on the one hand (see Amanda Lohrey, Richard Flanagan, Vicky Frost) and just shock including a wide range of reactions among them disdain and disbelief (Michael Connor. Do you think ‘Quadrant’ might mean ‘four rants’?).

So what’s in MONA worth commenting on? You get similar lists in all these articles. Richard Flanagan (a year or two ago) puts it nicely: It is a theatre of curious enchantments: from a wall of 151 sculptures of women’s vulvas to racks of rotting cow carcasses; a waterfall, the droplets of which form words from the most-Googled headlines of the day; the remains of a suicide bomber cast in chocolate; a grossly fattened red Porsche; a lavatory in which, through a system of mirrors and binoculars, you can view your own anus; mummies; X-ray images of rats carrying crucifixes; a library of blank books; cuneiform tablets; and stone blocks from the Hiroshima railway station destroyed by the atom bomb. Its most loathed exhibit is also one of its most popular: Wim Delvoye’s Cloaca Professional, a large, reeking machine that replicates the human digestive system, turning food into faeces, which it excretes daily at 2 pm.

Sure. I’ve mentioned the chocolate terrorist and the shit machine. I poked my head into the blanched library. But I didn’t spend much time on the rest of the list. Too much else to see. Mind you I wasn’t looking to be shocked; I just followed my nose so to speak.

I was more ‘shocked’ by Michael Connor’s article than anything I saw at MONA. He doesn’t like MONA, oooooo but he does love writing about it.

MONA is the art of the exhausted, of a decaying civilisation. Display lights and taste and stunning effects illuminate moral bankruptcy. What is highlighted melds perfectly with contemporary high fashion, design, architecture, cinema. It is expensive and tense decay.

W. B. Yeats eat your heart out! He derides the material on the Os, the ‘cultural Left’ (that mystery group who can also be located in ‘The Australian’ but perhaps nowhere else), the indications of popularity and the people making it popular (‘For the uncomprehending, uncritical, unmoved tourists it is meaningless matter superbly showcased—though if you threw out the art and put in a (gay) wedding expo, a psychic convention or a showing of hot rods they probably wouldn’t even notice, or care.’). He’s sorry for Walsh but cross about how much (completely undeserved!) money he’s obviously got, and he might be sorry too that Tasmania isn’t always bathed in ‘the autumn tones of a superlatively good colonial painting.’ (An example at right.) Oh wow. Such a buffalo wallow of derision — poisoned and poisonous.

Oh wow. Such a buffalo wallow of derision — poisoned and poisonous.

There is a lot about sex, death and religion at MONA; and there’s a lot that isn’t.

At the end of my visit I sat watching the quivering pen being driven by Cameron Robbins’ ‘weather powered drawing machine’ and its products. That might have been because there was a window which freed me of some of the intensity of the last six hours. But I wasn’t feeling shocked. The recent exhibition ‘Melbourne Now’ provides a strong example of just how hard it is to do what has been done at MONA. As exhibitions go it was massive, contemporary and mostly pretty feeble. Wunderkammers without the wunder. (The ‘Gallery of the Air’ was filled with things with ‘air’ in their title or nearly: LP covers of Air Supply and ‘Hasten down the wind’. Weak weak weak.) Some (but not much) fine craft; some meaning or wit (but not much). And is that perhaps because it was not driven by any specific idea or vision? So many people to satisfy, so much bureaucracy, instead of, as at MONA, the much discussed (and questioned if not maligned) ego/vision/tastes of its creator?

The recent exhibition ‘Melbourne Now’ provides a strong example of just how hard it is to do what has been done at MONA. As exhibitions go it was massive, contemporary and mostly pretty feeble. Wunderkammers without the wunder. (The ‘Gallery of the Air’ was filled with things with ‘air’ in their title or nearly: LP covers of Air Supply and ‘Hasten down the wind’. Weak weak weak.) Some (but not much) fine craft; some meaning or wit (but not much). And is that perhaps because it was not driven by any specific idea or vision? So many people to satisfy, so much bureaucracy, instead of, as at MONA, the much discussed (and questioned if not maligned) ego/vision/tastes of its creator?

David Walsh. Well good on him. Kerry O’Brien’s interviews with Paul Keating were on while we were in Tasmania. In the last of these Keating said: ‘Politicians come in three varieties: straight men, fixers and maddies. … Thatcher was a maddy. Charge in and get it done. Not that I want to be in included in any company with Thatcher; but I am certainly a maddy. Absolutely.’

Walsh, bless his heart, is a maddy and, more plumb than a finger up a duck’s bum, has a place in a long line of other great Tasmanian maddies: Dame Enid Lyons, Bob Brown, Matthew ‘Richo’ Richardson, Alannah Hill, Errol Flynn, Tiger Croswell. And Hobart and Tasmania are just the right size to allow him his head. Its very insularity reduces the pressure to conform to extraneous ideas about taste and to weaken the inspiration that has driven the character of MONA.

Paradoxically, Melbourne, eighteen times the size of Hobart, could only produce something more provincial (and Quadrant-like) because it is always looking somewhere else for direction and approbation. (And that somewhere isn’t there, trust me.)

What MONA says about art and what makes it so very very distinctive AND, hoorah, so best of Australian is: ‘This is something which has been made. See what you can make of it.’

Its objets do not sit sniffily in their glass cases saying, ‘Behold. Adore me. I’m a masterpiece’, even though from the perspective of craft so many of them are.

MONA’s art proposes. It engages. It says react, don’t presume, don’t cower. Fight back. Ask me questions. Check my provenance. Consider my future. Chase some of the cognitive prompts which stream from my presence. What do you think? What is your response? Why? Fill your brain. Wrestle with this. And that’s what makes it just so different.

That’s why, as Bruce Macavaney would say, it’s special. So special.

And the experience, how does MONA work so well?

This might be disappointing. No doubt you’d prefer a bolt of lightning or the earth opening beneath our feet, but in fact it’s just like the elements of very good education all present and combined.

There’s a hook, something a little tantalizing — the place’s reputation. There’s preparation, building expectation and readiness — the ferry ride and the exterior. There’s immersion, keeping you focused and directed to the task in hand — the interior design and layout. There’s a rich environment which will keep you stimulated — the exhibits. There’s scaffolding to prompt and guide your thinking, that you can connect with — the O material. And of all things, there’s reinforcement. You can do just what I’ve done and relive the whole experience again. And again. And again.

Let’s go out on a (short) limb here: The purpose of art is to generate a response (which of course has implications). Among other things that accounts for its evolutionary survival.

I leave you with these thoughts from the late great Charles Hardin Holley.

Tell you Mona what I wanna do

I’ll build a house next door to you

Can I see you sometime

We can go kissing through the blind

[alt renderings — A-we could go kissin through the blind: Bo Diddley

We can blow kisses through the blinds: Rolling Stones

Can I make love to you once in a while?: Quicksilver Messenger Service*]

When you come out on the front

Listen to my heart go bumpity bump

I need you baby and that’s no lie

Without your love I’d surely die.

* recommended: John Cipollina at his best with, among others, Nicky Hopkins, playing somewhere that looks like it could be Yulecart Gymkhana.