‘Unearthing the Welcome Stranger Nugget’ says the caption. ‘210 lbs’ it says, but received wisdom suggests 159 lbs or 72 kgs. Two foot long. All gold. So very rare. This happened at Moliagul in Central Victoria on 5 February, 1869. The nugget was found in the roots of a tree. Cornish miners John Deason and Richard Oates, pictured either side above, were paid just under £10,000 for it, about $570,000 in today’s terms which suggests they may have been short changed. That much gold today (depending on the day of the week and the state of the US stock market) would be worth $6.37m.

Gold. What’s the thing about gold?

It’s just something you dig out of the ground. (Usually. You might be able to find it in a wettish river bed.) You can’t drive it round, or build a house out of it. Why not, say, copper? Copper’s very good for the transmission of electricity. Zinc. There’s zinc, among other things a very useful anti-corrosive. Iron. Well, you can do just about anything with iron, and there’s plenty of it. Aluminium might be grey but it’s light. Where would caravans, just for example, be without aluminium? Are computers made out of gold? No. What? The mother board? Gold in the connections? All right then, … kitchen tables? No.

So what’s the big deal? I think we can all agree it’s pretty popular and has been for some time. Can any sense at all be made out its addictive attraction? Let’s try.

It’s durable. The gold in that necklace or ring you’re wearing might have been mined by Egyptian slaves. Gold is one of the seven generally agreed ‘noble metals’ (platinum is another) which scarcely react with other elements. Iron polishes beautifully, but it rusts, a problem for coinage. Unlike silver, gold doesn’t even tarnish. From a chemist’s point of view it might be thought of as almost spectacularly inert.

It’s comparatively rare. There are arguments about this but the weight of opinion appears to be that all the gold in the world that has been mined, ever, would fit into a 20 metre cube or, if you like, into an orderly pile just under 10 metres high on a tennis court. The same people who make this estimate believe that this is 3/4 of all the gold which will ever be mined (at present mainly from China, Russia and Australia, and then a dozen other bit players; 300 tonnes in a year is strong national haul).

And a propos of that, it’s heavy. I wonder if that matters. But the cube referred to above will weigh 171,300 tonnes, quite a lot. It’s one of the issues in heist pictures. There’s often a lot of to do about how they’re going to transport the loot because it’s so heavy blah blah blah. But when they’re actually carrying it to the van the problem seems to become of variable consequence. But yes, it’s heavy. A standard ingot of gold weighs 400 troy ounces, a unit of weight developed by the Romans — and that is 12.4 kilograms. You won’t pick that up without thinking about it. These ingots are a bit more than half the length of a school ruler (178mm), about the width of your instep (91.5mm) with the thickness of a bit more than the top joint of your (my) thumb (45mm). But unless you’re quite a special kind of person you don’t pick up a brick and, however heavy it might be, think hmmm must be valuable, do you?

It’s good for craft activities. Turning gold into jewellery (the use for nearly half of all extant gold) and coinage is altogether feasible. While the melting point of gold is 1064°C, you can smelt it, separating the base metal from its ore, via a range of far less challenging processes which were within the grasp of capable Bronze Age persons. Alloyed with copper it becomes rose gold; with nickel and palladium white gold. In its natural state it is malleable, in fact the most malleable of metals. If you’re good enough you can beat one ounce of pure gold to cover more than nine square metres (three queen-size beds). And if you’re really good you can beat it until it becomes transparent. The wealthy of all eras have been interested in covering available surfaces in gold leaf. One reason for this is because they could.

It is also amazingly ductile. One ounce of pure gold can be drawn into a wire five microns thick (5/1000ths of a millimetre) to be continuous for 80 kms without breaking.

I haven’t mentioned that in 24 carat form it is both edible and potable, nor that in some circles (if not the ones you move in) this is deemed to be desirable. Given that it is indigestible, you might question the value of that process. Nor have I mentioned that if you didn’t have some, and yes certainly a very small amount, nano particles, in your brain your neurons wouldn’t function. Uncorrodible gold provides the connectivity for the electrics of your neural system. (Ok. Check it out if you want. How does it get there? You can check that out too.)

Yes, all that. All that of course. But while all that glisters is not gold, all that’s gold does tend to glister. There is something about those warm tones, that feel, that heft. As Dr. Andrea Sella, Professor of Inorganic Chemistry at University College London, says so insightfully, and presumably after long and thoughtful study: ‘Gold is just so … golden.’

And that might have been what drew the hordes to Australia after 1851, multiplying Victoria’s non-Indigenous population by eight in a decade and generating a 300 percent increase in the Australian population as a whole over the same period. Sure gold is golden, but these enthusiasts also thought they were were going to land the big one. They were going to get rich.

* * * * *

The version of Australia’s experience with gold that I learnt at school went something like: 1851 Edward Hargraves found gold (at a place he called Ophir after a biblical source of gold tribute for King Solomon). Six months later gold was found at Ballarat and Bendigo: whoosh, ka-floooie! With the mild hiccup of the Eureka rebellion causing Australia to be a democracy, everything took off. Melbourne became Marvellous and everyone got rich. Modern Australia began. Bingo. Next please.

How much more tangled and various the story really is. Just some modest hints.

The first European find was a hoax. In mid-1788 — not much more than a moment after Australia had been colonised/ invaded — James Daley, a convict, reported to several people that he had found gold ‘some distance down the [Sydney] harbour’. On the pretence of showing an officer the position of his find, Daley escaped into the bush… for a day. I don’t know how far he had really thought this through. He received 50 lashes. Then he produced a specimen of gold ore. He was again invited to point out where he had found it. In addition, however, he was warned by an officer that he would be executed if it wasn’t true. Daley, whose middle name might have been ‘Arthur’, confessed that his story was ‘a falsehood’. He had made his specimen from a gold guinea and a brass buckle. Awarded no points for either persistence or craft skill, Daley was provided with an additional 100 lashes. He was hanged not long after for breaking and entering, but he had left a legacy. Many convicts continued to believe that Daley had actually found gold, and that he had taken the secret with him to his grave. And that is a story about gold. However fake the news, hope springs eternal.

As the Europeans started cutting their way through the Blue Mountains finds were reported during the 1820s, sometimes by reliable sources. In 1823 the first officially recorded find (near Bathurst by the colony’s assistant surveyor) occurred. There were other finds: to the north at Aberdeen and to the south in the Monaro. Another find was made near the mouth of the Tamar in Tasmania. It periodically appeared that wherever Europeans went in this country they might happen on something precious. This was of course in accord with a profound hankering. Why else would you live in this godforsaken place?

But, look, what do you do? You’re running a penal colony in a place you know next to nothing about. The ‘free’ element of the settlement is tiny and, even so, without special favours inclined to become bolshie. Even for getting what might be deemed essential done, labour is at a premium. Do you want someone running round shouting ‘gold? In fact ‘GOLD!!!!’ Not if you want a quiet life and a bit of steadiness.

The second headmaster of Sydney’s The Kings School (1839-40) was the Reverend William Branwhite Clarke who of all things had come to Australia because he believed the sea voyage would be good for his health. He was also, in the way of the times, an accomplished amateur geologist (eventually informally crowned the Father of Australian Geology). In addition to tending to his parishioners spread across the dales and hills of western Sydney, he spent time ‘ascertain[ing] the extent and character of the carboniferous formation in New South Wales’ (from his letter to the SMH, 18/2/1852). He found gold embedded in quartz at a number of places, most notably at Locksley just on the western side of the Blue Mountains in the 1840s. Early in 1844 he showed Sir George Gipps, the governor of New South Wales, some specimens he had found. Gipps asked him where he had got it and, when Clarke told him, famously said, ‘Put it away sir or we shall have our throats cut’.

Governor La Trobe provided much the same advice to a farmworker named Smith who found gold in Victoria’s Ovens River in the same year.

In 1846 gold was found in the Adelaide hills of the ‘free’ settlement South Australia. This find was greeted with great enthusiasm. Its first products were turned into a brooch for Queen Victoria. A company was formed with a public share offering which initially skyrocketted. Regrettably its total all-time output came to 24 ozs. Another gold story. You don’t always get what you want. The finest prospect can be a chimera.

But back to Victoria, the number of these finds began accelerating, and they were not confined to any particular area. Hundreds of kilometres separate Chiltern, Smythesdale, Bright, Warrandyte, Daylesford, and Omeo. Publicity about the 1848 Amherst find in central Victoria prompted what might be called the first ‘rush’ in that colony. About 100 potential diggers travelled to the site, but Governor La Trobe sent troopers to thwart any trespass on Crown Land (almost all of Victoria at the time). Nonetheless samples and nuggets were trickling their way secretively to Brentani’s jewellery shop in Melbourne’s Collins St for payouts. The cover was blown. (Another gold story. Word will get around, and ever so smartly.) The impact of the news of Hargraves’ find at Ophir (just north of Bathurst in NSW) in February 1851 was already being felt in the Victoria. ‘Panic’ is the word used to described the reaction amongst the populace. How that would play out in practice, apart from immediately packing and setting off for Ophir, I’m not sure.

Just before Hargraves’ find, a mineralogist, George Bruhn, determined to conduct a survey of Victoria’s mineral resources. He found confirmed samples of gold on David Cameron’s station at Clunes in March 1851 and made this knowledge selectively public. James Esmond, at that time working as a builder in the area, discovered further payable deposits of gold nearby. Bruhn forwarded specimens of gold to Melbourne which were received by the Gold Discovery Committee on 30 June 1851. On 1 July 1851 Victoria became a colony independent of New South Wales … and the first gold rush, with Clunes as its focus, began.

But it wasn’t just Clunes. Gold seemed to be all over the place: finds at 31 different locations were reported in the new colony between July and October 1851. The fever had gripped. Brentani’s was receiving so much gold they regularly ran out of currency.

Who made these early finds? Workers of course, people with their eyes casting about and their hands in the soil. On 20 July Christopher Peters, a shepherd and hut-keeper, made the first find at Specimen Gully near today’s Castlemaine, an area which over time produced 5.6 million ounces of gold. He was ridiculed for picking up fool’s gold, and the sample was thrown away by William Barker, the station owner, who didn’t want his workmen to abandon his sheep. But, perhaps understandably, they had other ideas. Three other shepherds and a bullock driver immediately teamed up with Peters to work the deposits. In ten days chipping away at the quartz with chisels they made as much as they otherwise would have in a year. When Barker sacked them and ran them off for trespass, one of them, Frank Worley, wrote a letter to Melbourne’s Argus newspaper ‘to prevent them getting in trouble’ which announced the precise location of their workings. This letter was published on 8 September 1851. Within a month there were about 8,000 diggers working the alluvial beds of the nearby creeks. By the end of the year there were about 25,000 on the field. (Alluvium: material deposited by water, surface material, which could be sand, gravel, soil or, in some cases, gold.)

And it wasn’t just male workers. Among those credited with being responsible for the first finds near Bendigo were two women Mrs Margaret Kennedy and Mrs Julia Farrell who panned for gold with Margaret Kennedy’s four children: John 9, Mary Ann 7, and Mary Jane 2, and baby Lucy. John was among those formally credited with the first find but it appears likely that he and Mary Ann were helping to look after the other children. The nod is generally given to Henry Frencham, a journalist, who certainly made the loudest public fuss about his find. But he walked the talk. Between the end of November and Christmas Day 1851 he had mined enough to deliver a 3 lb bag of gold to the Assistant Commissioner.

By 1854 rewards of £1000 were being gifted to those who had made the breakthrough, Hargraves in New South Wales, a team led by Louis Jean Michel in Victoria and Thomas Hiscock who made the find at Buninyong which began the Ballarat rush. Any thought of containing the rush had vanished. The fever had exploded.

At the peak of the period we are talking about, more than three tonnes of gold per week flowed into Melbourne’s Treasury Building. During the decade of the 1850s Victorian diggings were responsible for 43 percent of the entire world’s gold production, worth in today’s terms about $12 billion a year. It is believed that the gold exported to Britain in the thirty years from 1851 paid off all of Britain’s foreign debt. Even more certainly, it was a key factor in bankrolling the British industrial and commercial revolutions of the second half of the 19th century.

The Victorian Gold Discovery Committee wrote in 1854:

The discovery of the Victorian Goldfields has converted a remote dependency into a country of worldwide fame; it has attracted a population, extraordinary in number, with unprecedented rapidity; it has enhanced the value of property to an enormous extent; it has made this the richest country in the world.

* * * * *

What is gold? Where does it come from? And why was there such an abundance of accessible gold in Victoria?

Stardust is close to one correct answer. Strap yourself in carefully now.

It can be firmly asserted that the only elements which existed in the universe 13 billion years ago were a lot of hydrogen atoms, rather fewer helium atoms (generated by fusion reactions) and a small amount of lithium — very simple elements. More complex elements were formed by the heat and pressure present in the cores of stars. Explosions would disperse this matter across the universe.

But elements like platinum and gold were too complex to be formed in this way. Current theory has it that they have emerged from the collision of two neutron stars.

Neutron stars are born from the explosive death of other, larger stars, a violent supernova which blows the outer layers off the original stars. In astronomical terms these stars are physically tiny, about 20kms across, but with a mass about 1.4 times that of our sun with an incredibly dense core. Gravity presses the material in on itself so tightly that protons and electrons combine (‘melt’ is one description) to form neutrons and that’s where the stars get their name. On average, gravity on a neutron star is 2 billion times stronger than gravity on Earth. In fact, it is strong enough to significantly bend radiation from the star in a process known as gravitational lensing, allowing astronomers to ‘see’ some of the back side of a neutron star at the same time as the front side. The nature of their birth causes immensely rapid rotation sometimes as fast as 43,000 revolutions per minute.

The earth is about 4.543 billion years old. Gold was not present at its origin. It didn’t begin to arrive — as stardust (or meteorites and other space objects peppering the earth’s surface) — until at least 200 million years later.

There is gold everywhere on earth including in the oceans, but mostly in insufficiently concentrated form to collect. The most common natural method of concentration of gold is through the ancient workings of immensely hot fluid inside the Earth’s crust. These fluids have often moved through rocks over a large area and dissolved gold and other minerals. When these fluids cool or react with other rocks the dissolved gold precipitates into cracks or fractures forming veins. In Australia this concentration of gold took place in the Earth hundreds of millions of years ago in the eastern states, and thousands of millions of years ago in Western Australia (where even larger deposits have been found).

As well as gold, these fluids can carry other dissolved minerals, such as quartz. This is why gold is often found with quartz. These are known as primary gold deposits and to extract the gold the rock containing the veins of gold has to be dug up, crushed and processed. Adding a note of controversy and danger, cyanide is often an important part of this processing as it can be used to dissolve and bind to gold.

Some rocks containing gold veins are exposed on the surface and erode away. The gold that these rocks contained has been washed down into creeks to form alluvial (or secondary) deposits. Because gold is heavier than most of the material moved by a creek or river, it can become concentrated in hollows or trapped in the bed of the river. These deposits can be worked using a gold pan or cradle and it was those deposits which produced most of the gold found early in the rushes of the 1850s. The largest alluvial goldfields extended over distances of around 10 kilometres and produced more than 100 tonnes of gold.

Why in Victoria? As noted, larger deposits have been found in Western Australia, but at much deeper levels.

Gold is found in cracks and fissures of sedimentary rock. There are major volcanic geological zones in Victoria, but there also substantial sedimentary areas which are riven by a series of fault lines running roughly north-south: Yarramaljup, Moyston, Avoca, Mt William, Governor, Kiewa. Several of these fault lines are closely associated with gold sources. Major earthquakes, slippage and movement along fault lines will expose new strata, but it is believed that in the case of Victoria more frequent small-scale earth movements were far more influential in making gold accessible.

Conditions were optimal for finding surface gold and an unusual proportion of nuggets. Far more gold is found in ‘reefs’, veins most frequently found in quartz.

A competitor to The Welcome Stranger for the largest single deposit of gold ever found is the ‘Holtermann Nugget’. And right here is Holtermann with his ‘nugget’. A Prussian who left his country to avoid military service, he set up a mining operation near Hill End in NSW which for many years was unproductive. Then on 19th October 1872 a midnight firing of explosives revealed a ‘wall of gold’ of which the ‘nugget’ was part. Weight: 630 lbs, Height: 4 ft 9 ins, Width: 2ft 2ins, Av thickness: 4 ins, Value £12,000. But it is not a nugget. It is a ‘specimen’, a matrix of slate, quartz and gold, reef gold, which when crushed produced 3000 troy ounces of gold, quite enough to make Holtermann a rich man.

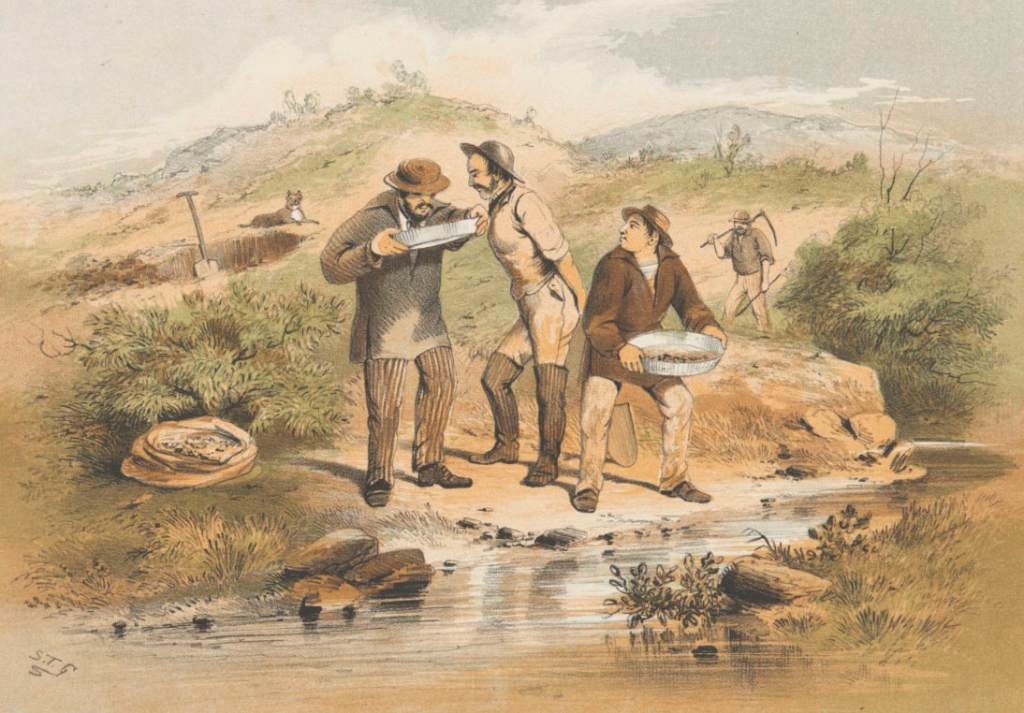

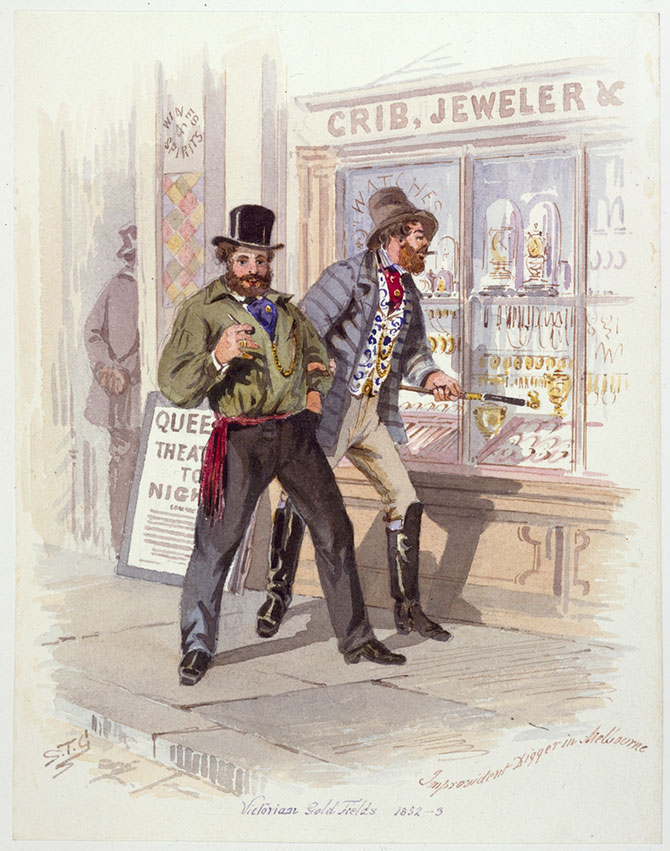

I wanted to put in a photo or two of the goldfields but even in Rod Hall and David Moore’s giant and superb Australia: Image of a Nation 1850-1950 there are no photos of goldfields or gold miners. There are paintings and sketches. S. T. Gill, the most prolific and insightful, is represented above. Von Guérard has some offerings but they are in strange circumstances which will be described below. On first try I found one photo of ‘Sandhurst’ (Bendigo) in the early-1880s, but the mining had become industrialised by then.

It’s not a digger with his 8 foot by 8 foot claim (expanded to 12 foot by 12 foot after the Eureka rebellion), just arrived from … anywhere. There are lots of remnants of Cornishmen in the diggings, but name them really and you won’t be wrong: Italy, Sweden, Russia, California even, and China beginning a relationship that never really got past awkward. Scotland. The entire collection of my forebears arrived in Victoria between 1852 and 1868, the McRaes in 1852. There was at least a gully full of Canadians at Ballarat. There were Murderers at a Flat out of Castlemaine. Anyone from anywhere really.

A digger wrestling with the quartz and wondering when he’ll hit a lead, freezing and wet in the middle of a Ballarat winter, wasting away at the height of a Mount Alexander summer. Using what for a bathroom? Finding food where? And, although they weren’t allowed to work on Sundays, not daring to take a holiday or even to leave his/her claim. When gold was discovered at the Forest Creek diggings just out of Castlemaine it is reported that some diggers stretched themselves out over their claim and didn’t move for several days (they must have, but you get the idea) until there was some formal recognition of their right.

The first photos were taken in Australia in the mid 1840s so the technology existed, and you might have thought it would have been applied to the most momentous events occurring. Perhaps photographers had turned themselves into diggers and were just too busy. Or perhaps it was such a specialised activity it didn’t find its way into the higgledy-piggledy world of the diggings.

But now I have had expert correction. There were photos taken of the Victorian goldfields in the 1850s, thank you Deidre, by Antoine Fauchery and his mate Richard Daintree. On review their photos of local Aboriginal people of the time are quite simply remarkable, but those of the diggers can look a bit posed or washed out.

For my own reasons I have chosen to let this choice stand: twenty years later (1872), and not in Victoria at all but at Gulgong, not so far from Hill End.

I think the clothes would still be pretty close to the mark. Yes to the hats, the windlass, the mullock heap. Yes to the beards, probably the tools, certainly the type of locale … and the scale of the enterprise.

And it’s Gulgong, which allows me to include a joke which has given me enormous pleasure over the years. (Reflecting very badly on me. It is so weak!!) All I can plead is that it had some special significance for me at certain moments in the years I spent roaming western New South Wales.

Prince Charles was on a tour of Australia and Gulgong was included on his itinerary. (Nb. Let’s not talk Gulgong down. Anthony Trollope also visited in 1871.) At the official reception he wore something odd on his head that looked just a little like a Davey Crockett Hat. Or something. It was the talk of the evening of course and finally the Mayor summoned enough courage to enquire about it. ‘The hat?’ His Royal Personage replied. ‘Quite wonderful isn’t it!’ ‘ But does it mean something?’ the Mayor asked. ‘I’m glad you enquired’, responded His Terrific Eminence. (You must be using a Prince Charles voice here, right way down the back of the throat.) ‘I mentioned to my father, The Duke, that I was off to Ooooorstralia, and he said, where you going? I ran through a few of the places I was scheduled to visit then mentioned Gulgong. And he said, ahhhhhh wear the foxhat.’

* * * * *

This has been a long preamble to a series of stories about walking the Goldfields Track which starts at the pinnacle of Mt Buninyong and ends (for me, it must end, can only end) at the Alexandra Fountain at the intersection of View Street and Pall Mall, the absolute heart of Bendigo about 210 kilometres away.

I have known about the Track for years and owned a guide book for at least five or six. The Guidebook (this one now superseded by a new edition) is a work of great art, a really good guidebook prepared by capable people who know their business, and it was enticing.

But I couldn’t get over the idea that, regardless of the weather, which would almost certainly be terrible — too hot too wet too cold too muggy — it would be weeks of walking on quartzy gravel through unvarying, and undistinguished, grey forests of box and stringybark. Not much to see, not much of interest. Quite a few days you would have to end up nowhere and make complex arrangements to find a shower, some food and a bed. I’m not embarrassed to admit I’m disinclined these days to spend a day, or several, carrying a 25 kilo pack and then camping.

A confluence of events changed my view.

Covid came along and Melbourne’s second lockdown went for months and while you could go for walks — and we did endlessly to the point where I got very sick of the first 500 metres in any direction from our front door — you couldn’t go for a walk in the bush. Not only could you not leave town; you couldn’t travel more than 5 kms from your home. There are people so much worse off in the world, but I chafed.

One thing that had happened — and we knew about this from illegally walking through the gardens of Eaglemont, Heidelberg and Ivanhoe and the natural gardens along the Yarra — was that it had been a wonderful growing season, a comparatively long cold winter, a late wet Spring and, almost perversely, the natural world had never looked more verdant and fertile.

When the opportunity came to get out of town we took it quickly and enthusiastically. But what to do? How to really make the most of it? An old favourite or something new?

We’ve been walking around Creswick, one of the towns on the route, for years, good walks, 8.3/10 walks, interesting and varied. Creswick where W.G. Spence, one of the founders of the Australian Workers Union, grew up; home to the artistic Lindsay family; birthplace of John Curtin, quite possibly Australia’s greatest Prime Minister. A collection of big houses and worker’s cottages, some grand institutional building, some defining waterworks and other signs of unrealised ambition. Melbourne University’s forestry school was established here (with, tucked away in its arboretum, Australia’s Number One pinus radiata). There are two good pubs and, Lord help us, Le Péché Gourmand (‘the sinful eater’), a really good patisserie with outstanding coffee.

I knew the Track went through Creswick — we had often seen the waymarks — but I couldn’t quite figure out the prior leg. It’s about 20kms by road from Ballarat to Creswick and most of the way it is open paddocks until you get to quite a stretch of suburban Ballarat. How could you make that into an interesting walk? We could go and see, and if it was no good we would at least have been in the open air and seen our friends at Le PG.

So very early in the morning of November 16th 2020 we found ourselves walking down Mair St to the Ballarat Station in order to catch the bus to Creswick. The Track is usually described running from the south to the north. We were going the wrong way and we weren’t beginning at the beginning. But all that is easily forgiven. I think we were doing it backwards because we prefer to wrestle with public transport early in the day and our car was at Ballarat, and anyway we weren’t starting The Track, hadn’t really given any thought to that — we were just going for a walk.

The bus trip was pleasant and we got off somewhere near the right place, had a cup of coffee and a croissant with a selection of emergency workers easing their way into the day, and headed off …