That’s not one of them. Just a photo that says you’re somewhere else. The steam coming out of the pavement grate … could be anywhere really but ingrained cultural habit would say New York. And ingrained cultural habit would be right. Outside our hotel, which might have had fleas in the carpet, on 26th Street in Chelsea.

We’d come to New York as a waystation but also I wanted to go to MOMA to look at a specific set of paintings, to encounter them again really, to sidle round a corner and go OMG. Woooo. Look at that. Then move on a bit and say, Hahh! They’ve got that too! Quickly spin round and over my shoulder catch of a glimpse of … no they couldn’t have!! And after an hour or two of that subside saying, Crikey. They’ve got everything.

This wasn’t speculation. I’d done it before in 1988 and I wanted to relive the experience.

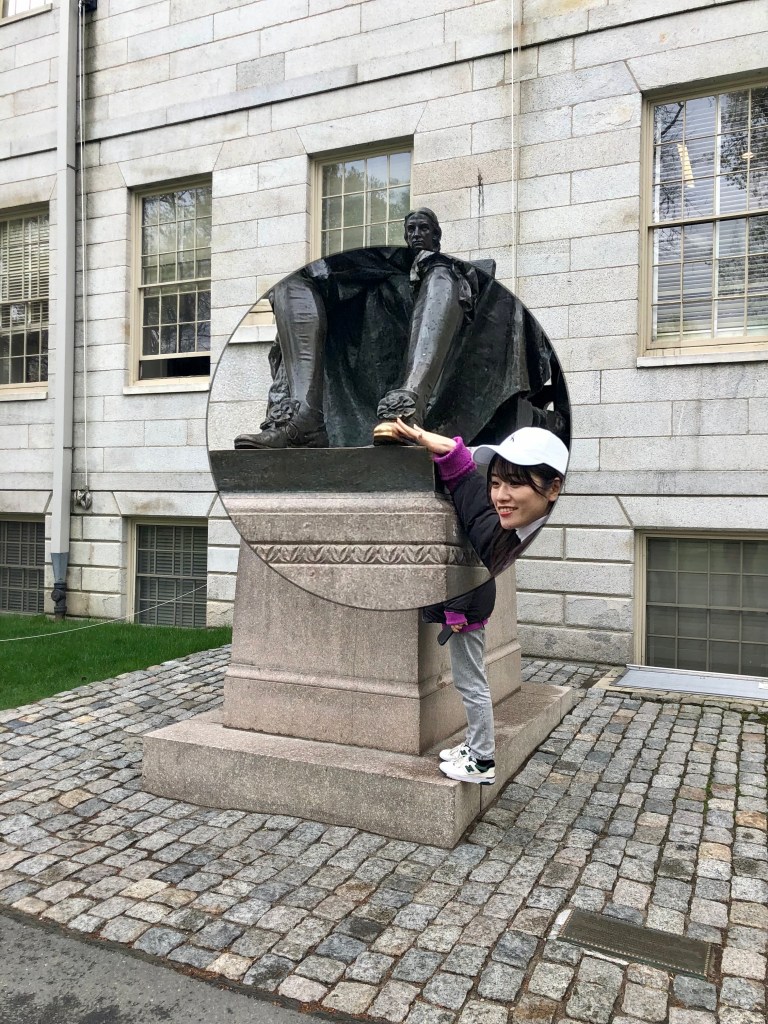

It was a cold wet Sunday morning. We walked the 27 blocks up 5th Avenue past the church where Logan Roy’s funeral was held, stopping off in a side street to do something with what Americans call food, arriving at the Museum of Modern Art just as most of the rest of the population of New York did too. The crowd was thick; well-organised in the very fancy and enormous building that is no longer new, but seriously thick. I think perhaps 6 or 7 thousand, more, the populace of a good-sized Australian country town all at once. So many art lovers in New York.

As reported elsewhere, we quailed and went and hid in a side exhibition called ‘Chosen Memories’ in which we became absorbed. Inter alia it had a giant tapestry of a Mexican supermarket docket, 3m high I’d guess. $M18.35 change out of 100, the big expenses being Cheetos and Sant Choco. It all made sense. Although no Coke. Maybe they were coming back for that later.

But the quailing was temporary.

• • • • • • •

It should come as no surprise that the heartland of an empire should plunder its dominions: a matter of duty really. For historical validation the British Museum, the Louvre and the Uffizi are comfortable testimony. Do you really expect Britain to send the Elgin marbles back to Greece or the Rosetta Stone back to Egypt? Come on. The thing is, they wouldn’t look after them.

And it so happened that the American Empire was approaching something of an epiphany in the early 20th century at the same time as painted and sculpted European art had twisted on its heel and was going off in directions that had previously been invisible.

It wasn’t a group of impoverished but well-meaning bohemians that recognised this and decided it would be good to import some examples to look at. As Tom Wolfe writes in The Painted Word: ‘Modern Art arrived in the United States in the 1920s not like a rebel commando force but like Standard Oil. It was founded in John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s living room, to be exact, with Goodyears, Blisses, and Crowninshields in attendance.’ These names, even singly, represent amounts of money you and I can’t imagine.

The Empire has never really been The Government. An Empire is the government working at the behest of, sometimes along side of, mostly being ignored by formidable private interests.

And it was Mrs. Rockefeller who had been so moved by the Armory Show of 1913 which introduced America to Cubism, Fauvism, and Futurism that she thought she’d like one of her own that she could go and look at whenever she liked. (The hit of that show was Marcel Duchamp’s Nu descendant un escalier despite Theodore Roosevelt’s incisive critique that it was ‘not art’.)

Armed with a good eye and a profound bias for the new, not to mention a gigantic wad of cash, 29 year-old Alfred E. Barr, MOMA’s first Director, started buying art. Some he let slip. Philadelphia, for example, has definitive collections of Expressionist art, fantastic Impressionist works and the ambulent nude pictured above. Some he left in Europe. The major French galleries are competitive. But Barr got The Best, and they were The Best because he said so.

To go any further in this blog you will need to memorise this diagram of his definition of Modern Art and successfully complete a short test on its primary ideas. It summarises the story that Barr made up about Modern Art, the story that I learnt so assiduously in Years 11 & 12.

‘Purism’ and ‘Orphism’ have fallen by the wayside, but the rest remains sturdily mainstream. If he got the best of each category or ‘school’ he’d have the best of the lot. THE BEST of The Best. 👏👏👏

• • • • • • •

The Best. A challenging idea. When I look at lists of The Best works at MOMA — which may I say are legion and remarkably consistent — they also conform pretty closely to lists of the Most Popular works at MOMA. Marketing has done its work.

‘Is most popular best?’ is such an old question that it might be considered a keystone of dissension. So we’ll just let that one ride. The Best at what? When? Ah quibble quibble. Okay. Works from 1890 to 1930 that changed the direction of art and the way we thought about it. ‘We’? Okay not the common ooops nearly wrote ‘man’, person; the people who take an interest.

We’ll go through them, a Top Ten.

• • • • • • •

The top two tend to be out on their own. Van Gogh’s The Starry Night tends to win the people’s choice award although Don McLean’s song ought to disqualify it from any list. But there it is. This is my picture of The Starry Night.

You’d have to engage in a fist fight to see it properly, and it didn’t matter because I had seen it before and knew what it looked like.

What’s it got? Here, it is flanked by Portrait of Joseph Roulin, which with its largely green face might be considered more radical, and The Olive Trees which is similarly vivid, very much the same style, but with trees. There are other Van Goghs you might prefer. His self-portraits have an edge to them that his landscapes don’t. But this is the one they like.

Once you accomodate the tumult of the sky and especially the big whirlpool so centrally placed, it’s got colours you can enjoy (‘Forget-me-not blue’ according to MOMA’s description) and it is certainly an adventure for your eye: a study in vitality. The contrast between the sky and the cypress trees (reaching ambitiously high in the structure of the painting) and the vertical and horizontal definition of the town is one of the things that make it work. Critics discuss whether the planet Venus did in fact illuminate the night sky over Saint Remy in spring 1889, and how proximate the town is to studies he made of it (not at all) but that does miss the point entirely. You could put it on your wall and look at it every day and still enjoy it. It’s a painting, and before Vincent came along there weren’t many like it. 8.5.

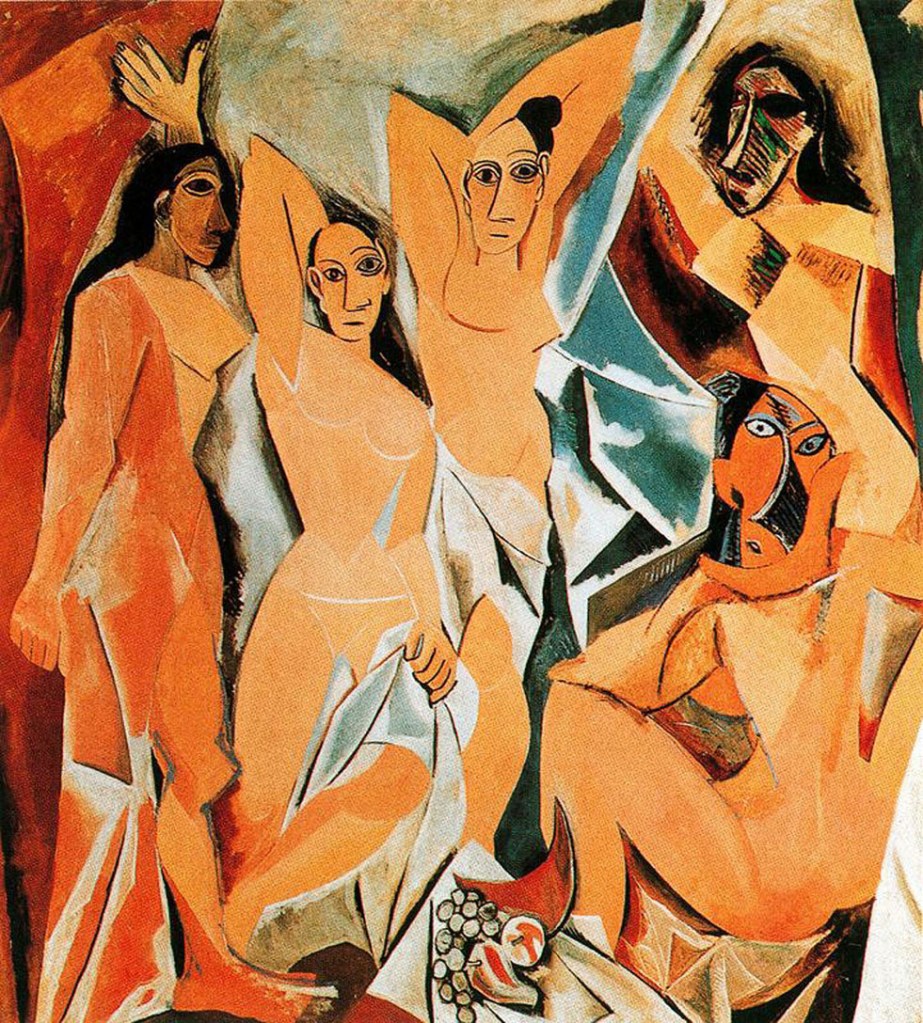

Number Two which is actually Number One for impact. Picasso.

It’s big. That’s one thing. Each edge measures about 2.5m. And it’s ugly isn’t it? They are supposed to be demoiselles for goodness sake, and from Avignon. (It’s first title was actually The Brothel of Avignon, but ignore that.) They are also divided into flat planes and, as so very widely noted, in three instances given heads influenced by African masks, mouths a line, eyes when you can see them … well, just dots really. If you want something to shake up ideas about paintings of clusters of naked women (of which there are so very many) this is The One. A bit of an outlier, but Cubism.

There is no doubt whatsoever about the significance of this painting. It shook the art world to its core. But is it any good? Still? Yeah. Quite captivating. The green dividing line and the way that’s been handled is very skilled. The still life at the bottom provides a strong offset of detail to the ‘blankness’ above as well as a reference to the face bottom right. And somehow the crazy eyes still catch and fix. Looking at it, you cannot avoid thinking, what on earth was he up to here? Politics 10. Art 7.6.

Footnote: I like his Girl in the Mirror, also at MOMA (of course), considerably more. It was the one that got on the cover of Canaday’s Mainstreams of Modern Art. An unquestioned 10.

Cezanne, Milk Jug and Apples. He always gets in the top echelon, but tagged as a Post-Impressionist, the school for the uncategorisable. I’m pretty sure it’s because of the way he puts his paint on. That mini-baguette has more than a dozen discernably different colours on it without considering the points at which they are merged. He seems to poke his paint on, dabbing, and so to find a crisp line is unusual. But there is something mild and deeply welcoming about the result. Sometimes he stops before he should, but this one has been painted right out. This is not one of the 91 Mont Sainte Victoires; the smarties who bought it decided it was better, and I think they were right. 10.

Dali’s The Persistence of Memory, just sneaking in from 1931. It’s about the size of a shoe box lid, and we couldn’t get near it. Widely considered to be the work at or near the apex of the surrealist movement. Like Picasso, Dali was a great craftsman and that is evident in this work. It is beautifully painted with a luminescence you can’t see here. But it’s the wrinkles in Dali’s mind that we come to look at and exclaim over.

Does it look dated now? I think only because of its familiarity. A lot of people have done crumpled watches, Alfred Hitchcock in ‘Spellbound’ for example. But Dali thought of it first. There are better surrealist paintings but this is The One. 9.

Henri Matisse, on the left The Dance out of focus and cropped awkwardly. It was a commission for a Russian businessman designed to fill up a hole on a very large wall, and I think it is its scale which makes it such a dominant work. And its simplicity and vitality. I saw it on the wall and could only summon an ‘Uh huh. There it is.’ The Red Studio, also held by MOMA, (they don’t do things by halves, they have the subs to come on if needed) is a much more interesting and complex work. Still The Dance is the one that gets The Nod. The Dance 6. Red Studio at least 8.5.

They’ve got it (them?) and it (they?) fills a room. Claude Monet’s Water Lilies. Three panels, together 2m high x 12.67m wide. The pinnacle of Impressionism. Sort of hyper-extended Impressionism really. I recognise the achievement but I just can’t get interested. However if you want a Monet, and galleries would remove their wisdom teeth with pliers to get one, this is It. Can’t even think of anything to say. 5 (for its reputation).

Henri Rousseau, ‘Le Douanier‘, the Customs officer, represents a school which doesn’t appear in Barr’s diagram and in many of the older accounts of modern art, Primitivism. The Dream is above. The Sleeping Gypsy at left gets a wall to itself and often comes in higher on the popularity stakes.

These are super paintings, engaging in ways that some of these others aren’t. They have implicit narratives — can you see the piper in the middle of The Dream for example? — that invite interpretation and involvement. They are also very carefully painted and carefully finished. I think they are significant because they give licence for the interior imagination and the various ways of rendering it to be taken seriously. It is a ‘three cheers for individuality’ moment. I think these are wonderful. 10.

The Fauves. Matisse gets listed under Fauvism sometimes, and it’s hard to pick The Picture but something by Kirchner or Derain would come close, and there was a huge selection of both. These don’t get on the popularity lists.

Ludwig Kirchner, Street, Dresden

Kees van Dongen, Modjesko, Soprano Singer

What’s the story? Colour. Colour colour colour. They took Van Gogh at his example and upped the stakes. I hadn’t seen the Van Dongen before and got very excited about it. 8 (a little bit muddy) & 10.

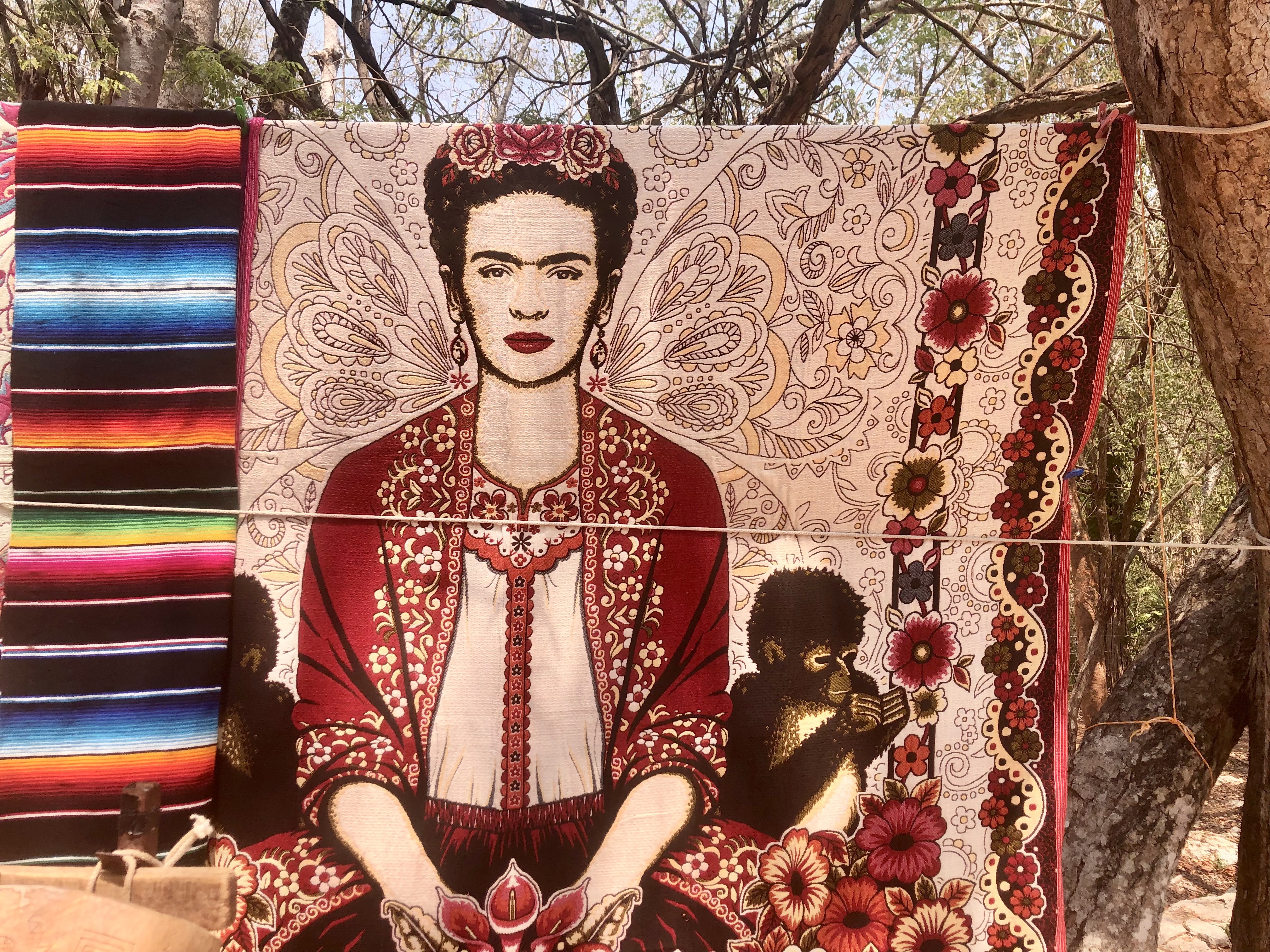

Self Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940) above, and on the left My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (or Family Tree) (1936). And, of course its Frida Kahlo, and perhaps a mystery. Cropped Hair is always in the top five most popular. Family Tree (also held by MOMA) never is but it indicates for me both why Frida is an important artist and why her work is so beguiling.

It is the intimacy of her sharing. Yes they are paintings, but they are fearlessly revelatory, self revelatory in a way that has almost become standard in contemporary women’s art. Men don’t seem to be able to manage it in quite the same way. Frida most courageously lifted a veil that hasn’t been put back. Significance 10. Art 9.

• • • • • • •

What missed out?

Clockwise from top left: Boccioni The City Rises, the centrepiece of Futurism; Chirico The Love Song, by no means his best but the fans love it; Piet Mondrian Broadway Boogie Woogie, very stiff to miss out on top ten, representing a very powerful direction that none of the others do, Formalism; Andrew Wyeth Christina’s World (1948), an American favourite which is hung to introduce the galleries where these wonders are stored; Jackson Pollock Number 1A, 1948, MOMA was the first major gallery to buy his work and recognise Abstract Expressionism; Edward Hopper Gas (1940) more terrific Americana.

And two fine representatives of my all-time favourites.

Paul Klee, Around the Fish

René Magritte The Menaced Assassin

And they are all in MOMA (and so incredibly much more). You can go too, and see what makes the art world turn.

• • • • • • •

When you see these paintings, it is almost impossible to see them just as themselves. They come embroidered with numinous histories, reputations, publicities. It doesn’t make them bad, neither does it make them good, nor The Best, an utterly spurious notion.

It is fashionable these days to turn your nose up them. Old hat. Uncool. If you want to collect them buy a tea towel. But goodness it was great to see them. Old friends are always better in the flesh.

Now to some other revolutionary moments.