substrate /ˈsʌbstreɪt/ noun

- an underlying substance or layer

- the surface or material on or from which an organism lives, grows, or obtains its nourishment.

I liked this. In fact I loved it. I loved it all. ‘Adventures in Memory’, a massive retrospective of the works of Keiichi Tanaami which opened at Tokyo’s National Art Centre just as he died at the age of 88. It simply teemed with life and vitality, an electric sensibility pouring out versions of the fantasmagoria assembled in his mind. Room after room after room.

(He had a thing about bridges which he assigns to an early experience of Hokusai’s ‘One Hundred Bridges in One View‘.) It wasn’t just the ones on the walls which you might think of as messy. He seemed able to do anything, and so much of anything: collage, 3-D sculptures on all sorts of scales, storyboards, toys, magazine layouts, marketing art, video, a wall of his own thoroughly credible ‘Picassos’ as per the Dora Maar period.

And this is him.

Expressionless, opaque. Those art works emerged from him.

This seems to me to be such a telling photograph. Can we say that simmering underneath the so carefully ordered and stable surface of Japan is something quite different to which art provides a clue? Japan? Japanese? Generalisations are always flawed, ridiculously flawed, but I have to think so. Perhaps it’s obvious. It’s certainly not an original idea. That surface order — Myrna was scolded and firmly redirected after she had walked the ‘wrong way’ round a room in a gallery at Nagasaki — must surely disguise a tumultuous underground, heaving, wild, passionate, perverse, transgressive … and sometimes, often, great fun.

• • • • • • • •

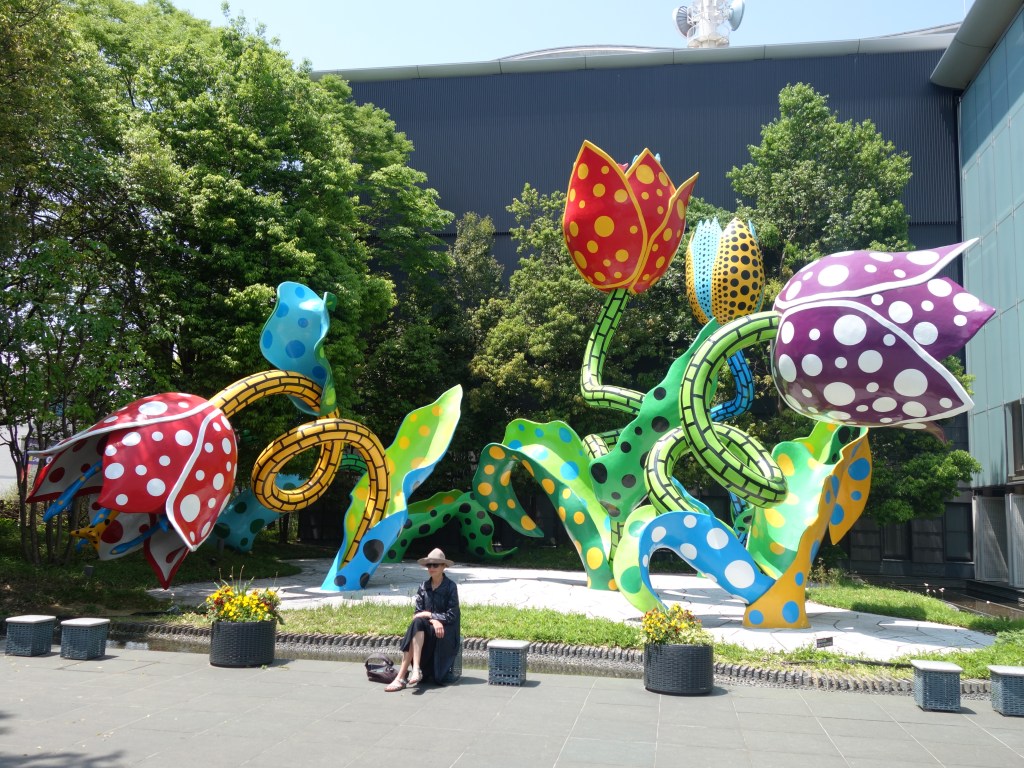

Soon to be the subject of a major exhibition in Melbourne, Yayoi Kusama is known for her dots, pumpkins and ‘infinity nets’. Above, Myrna is sitting at the site of a major retrospective in Kusama’s home town of Matsumoto where we also found reasonably contemporary versions of her ‘infinity nets’.

Critic Claire Voon has described Kusama’s mirror exhibits as being able to ‘transport you to a quiet cosmos, to a lonely labyrinth of pulsing light, or to what could be the enveloping innards of a leviathan with the measles’, a witty and insightful comment on their absorbing and otherwise anodyne nature.

This pumpkin of hers is how visitors to Naoshima, the ‘art island’ in Japan’s inland sea, are greeted.

No collection of contemporary Japanese art would be complete without her being represented. But for that work. Not this.

She left Japan — ‘too small, too servile, too feudalistic, and too scornful of women’ — for the United States when she was 27. I think it would be fair to say that she had considerable trouble establishing a presence. She was also left reeling from the theft of several of her ideas by Claes Oldenburg and Andy Warhol. Female, Japanese … short, what chance did she have really? Her recourse was to very public nudity and very public sex. She had found another surface for her dots. And another way to work out her demons.

She became briefly famous at the time for offering to have sex with Richard Nixon if he stopped the Viet Nam war.

When she returned to Japan she was modestly famous, but for being a ‘Scandal Queen’. Matsumoto Secondary School expunged any reference to her from the relevant Year Book and school records, one of many forms of social elision which she incurred at the time. She committed herself to a mental hospital where she chose to live for some years. It was the late 1990s before her work began drawing interest, the interest which exploded — EXPLODED — internationally a bit over a decade ago. She describes the purpose of her work as ‘self-obliteration’. This has not come to pass.

• • • • • • • •

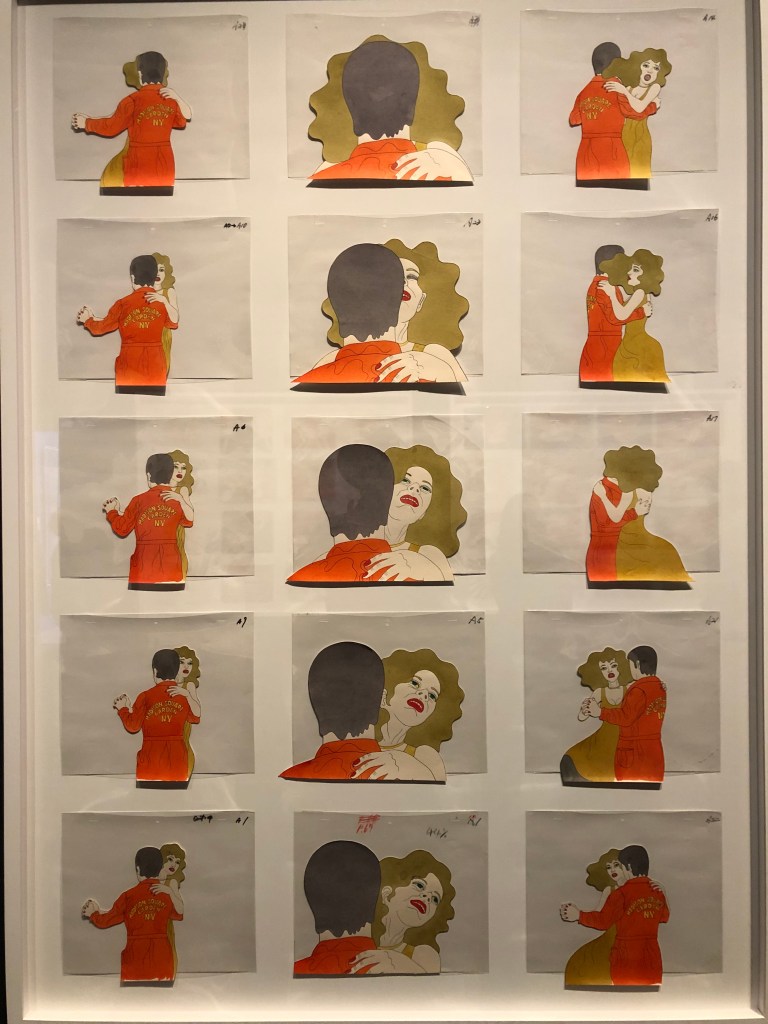

Yasumasa Morimura, who we found in another major exhibition at the Osaka Gallery a few years ago, has found another form of ‘self-obliteration’.

This is one of a series of 16 works ‘Revolutionising the World through Personal Pain: An inner dialogue with Frida Kahlo’. And yes that’s him.

So’s that. A photo of a made up and painted face, jacket and background.

Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes. What’s he look like? Like that I suppose. No idea. Or perhaps like this, standing at the window in his version of Vermeer’s studio.

His work extends far beyond these portraits of ‘self as others’. His series dismantling and rebuilding Velazquez’s Las Meninas, ‘What the painter was looking at’ … What can I say? So many brilliant tricks, so many trompes of the oeil, so much fertility in the imagination, such brilliant craft skills. And so gloriously nutty.

He is not playing by the rules.

• • • • • • • •

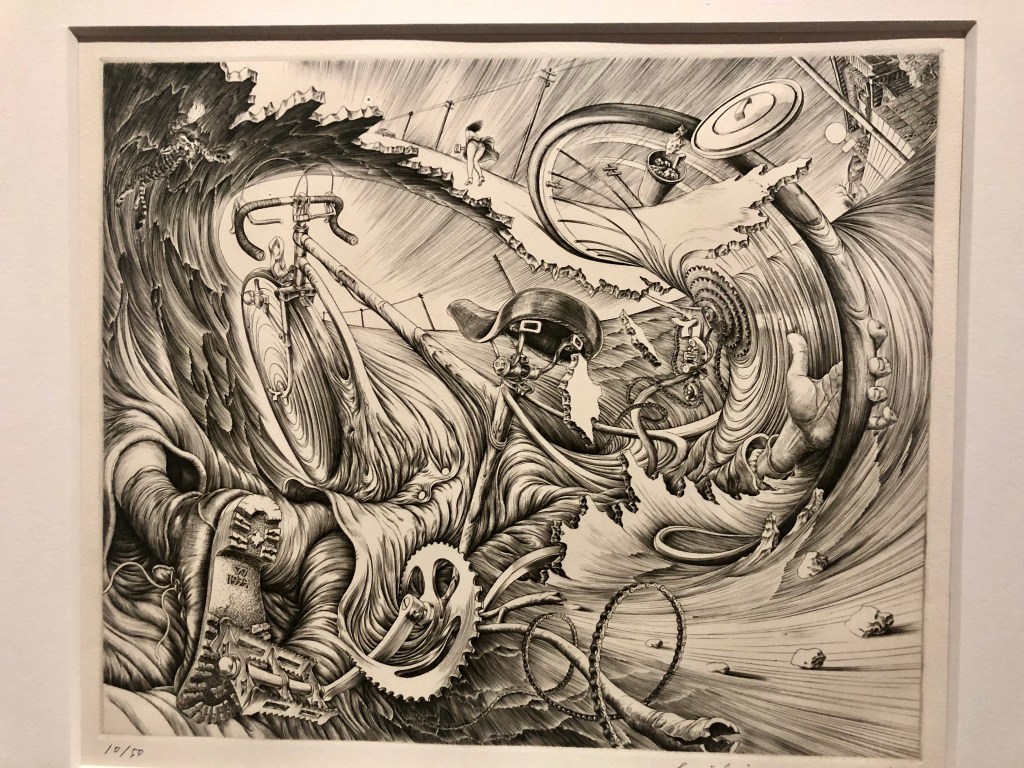

In Nagasaki we found the works of a local, Chihiro Watanabe. Incredibly skilful woodcuts and mezzotints. This one was called ‘The Weekend’. Mesmerising. Look at it carefully for a few moments. There is so much going on. Find the cat for example. (Top left.) What’s the date on the boot? (1979) Where’s the road sign? (Top right.) What’s the wave made out of? (Goodness knows, but it’s chunky.) That back wheel … (He might be mending it …?) It repays.

But even apart from the eventful bike ride, how’s he feeling?

A lot going on there.

• • • • • • • •

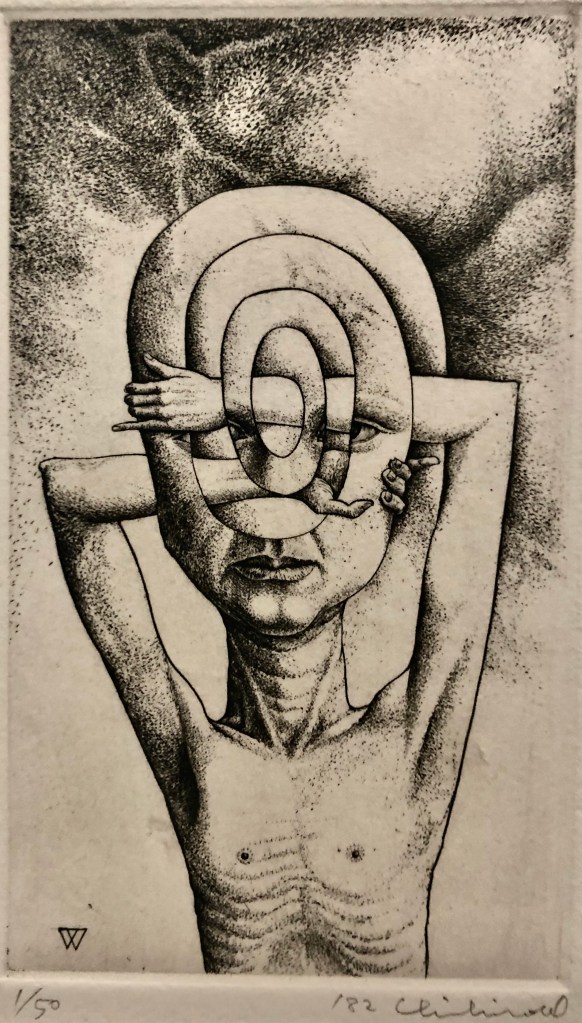

The figure. I must say something about the figure.

There were, of course, colour field abstractions on show. Below is one of the very good ones we saw, in Kyoto this time quite close to the line of figures above. (Even with this one there are glimpses of ‘the figure’, dressed arrows, the eyes.)

But what I want to say is that there is a focus on the figure in contemporary Japanese art that is marked and that you mightn’t find elsewhere. And also that it is a particular form of concentration.

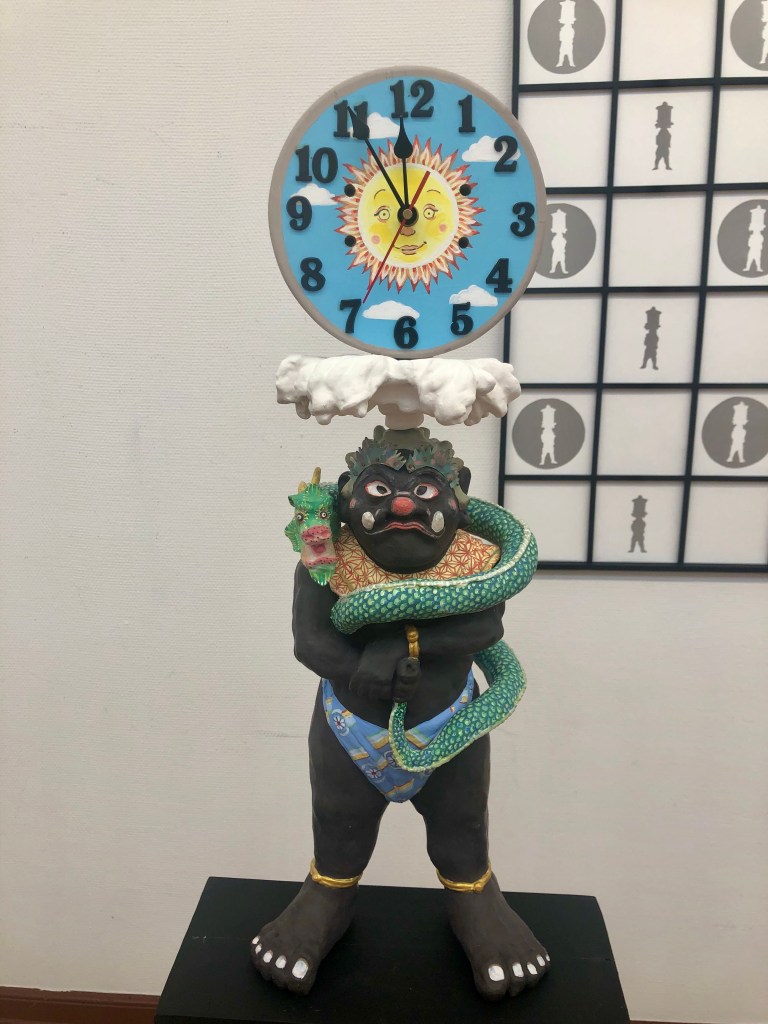

The figures I am referring to are not portraits. The ‘figures’ are not contemplative or pensive or just sitting or standing there. They’ve got a cloud and a bucket of water with someone swimming in it on their head. Or they’re encircled by a dragon. They are embedded in a narrative. To understand them you must look further, you must see more. They are action. Like in a cartoon. (What does Tanaami’s work remind you of after all?) Like in manga. Like in hentai. It would not be enough for me to do a drawing of you however outstanding, however perfect, or realistic. I would have to do something that made it BOUNCE into a story.

• • • • • • • •

In Tokyo we also found an exhibition of a selection from Ryutaro Takahashi’s massive collection of contemporary art (more than 3,400 works) at the Museum of Contemporary Art. Takahashi initially wanted to be an artist, but exposure to work by Yayoi Kusama when a student ‘made him aware of the limitations of his own talent’ and he returned to medical studies and became a psychiatrist. Who knows what he found in art to make him such an avid and perspicacious collector (and how he could afford it!), but what he has collected would be the equal or better of all but a few of the major galleries in Japan. (What he does with it all when it is not on display is another rather pedestrian but for me unavoidable question.) But it was on display, and it provided a comprehensive survey of contemporary Japanese art.

I liked this as much as anything else.

It is heavily populated (not least by birds); in fact it is packed with life and detail which you can’t really see here. My apologies. The work below by Makoto Aida Harakiri Schooldays will be more legible.

As will these works by Takashi Murakami.

This one is called Embodiment of “A” and, typical of guardians of shrines, it has a partner, Embodiment of “Um”. This was initially part of an exhibition called ‘Japan Supernatural: Vertiginous After Staring at the Empty World Too Intensely, I Found Myself Trapped in the Realm of Lurking Ghosts and Monsters’.

My case doesn’t rest here, but there is enough evidence to wonder about the substrate from which all this has grown.

And just by the way, how compelling is it that a psychiatrist is collecting this (wonderful) material?

And now … this is Jamboree-EP, 39 blocks of camphor wood carved by Mori Osamu (at left) collectively about 4 metres high. And yes, Elvis, Fat Elvis, with a superbly carved face. Iconic figure. The first universal celebrity. Maybe. Probably. Here in the middle of a signature gesture (with, what, ‘Suspicious Minds’ coming out of his mouth?) our attention is drawn to the fact that he has a broken finger. Broken off that is. Below a tuft of chest hair he has spectacular female breasts, or at least breasts constructed as spectacle. His left hand is caressing what can only be his erect penis. And he seems to be sitting on a pile of his own shit.

A lot of buttons are being pressed here. What are we to do with it? So many taboos to manage at once. Is disgust the only possible reaction, and if so why? In the flesh so to speak, when I was there looking at it I didn’t want to look away. There is something mighty about its transgressions, something that insists on your attention, insists on examining the nature of your responses — because there will be more than one. What are those breasts about? Why so much shit? Is it representative? Perhaps of all the rubbish, literal and figurative, that he consumed? Can I aggregate the sum of its parts, can I put it all together … and if so what have I constructed? What is it? Or is it too much to manage?

A lot of buttons are being pressed here. You might forget the work and think about the artist. What was he up to and why? Like Kusama, did he feel he needed to make a splash, a name for himself, by going above and beyond so many conventional boundaries? I am inclined to think that — as might happen with a lot of artistic construction — he became immersed in this monster project (yes, a monster project) and like us having to make of it what we will, so does he.

A lot of buttons are being pressed here. I didn’t want to look away. There is something so enormously pungent about it. It was the highlight of an astonishing exhibition.

• • • • • • • •

There is no doubt that personal trauma may play some role sometimes in feeding and shaping the substrate which produces such vividly crackling art work.

Going right back to the start of this blog, Keiichi Tanaami’s artist’s statement was unusually clear, honest and informative. It began:

“I was rushed away from my childhood, a time that should be filled with eating and playing, by the enigmatic monstrosity of war; my dreams were a vortex of fear and anxiety, anger and resignation. On the night of the air raid [in 1945; he was nine], I remember watching swarms of people flee from bald mountaintops. But then something occurs to me: was that moment real? Dream and reality are all mixed up in my memories, recorded permanently in this ambiguous way.” As expressed in his work, those memories are full of American planes, searchlights, bomb blasts, ‘crimson flames covering the entire night sky, flickering and wavering in a semi-circle like an enormous arched bridge … a stunningly beautiful yet terrifying sight to behold.’

Yayoi Kusama was born at a similar time. Her experience of the war included being pressed to work in a factory sewing parachute materials. She describes this time as ‘living in closed darkness … listening to air raid alerts.’ Prior to this she suffered at the hand of an abusive mother who besides destroying her art works insisted that she spy on her philandering father. ‘I don’t like sex’, she has said. ‘I had an obsession with sex. When I was a child, my father had lovers and I experienced watching him with them. My mother sent me to spy on him. I didn’t want to have sex with anyone for years […] The sexual obsession and fear of sex sit side by side in me.’

There might be stories of this type shared more widely by some of the artists who feature here. A whole section of Ryutaro Takahashi’s exhibition was organised around the impact and associated trauma of the Great East Japan Earthquake and the Fukushima disaster. The curator of the exhibition thinks this is a category.

But I look at these works and commonly think religion, Japanese religion. Sometimes very clearly for the forms, almost copies in some cases, but also for their stories and teeming and unusual populations, their ‘figures’. And ‘religion’ meaning something a bit different, meaning something like the background stories that shape our understanding of ourselves.

• • • • • • • •

Shinto is the oldest and most pervasive of Japan’s religions. It proposes an animated world. Kami, spirits, can be found in rocks, rivers, mountains, trees, and most definitely in waterfalls. They can and do influence the trajectory of your life in complex and enigmatic ways. Their effects may be benign or malevolent. It is a world in motion which is unsystematic and heavily subject to your own imaginings.

Japanese Buddhism is its close friend and near relation, a very fine example of syncretism, ‘the [often scarcely conscious] amalgamation of different religions, cultures, or schools of thought’. (In my blog about Nagasaki and Dejima I mentioned how the Catholic priests returning to Japan after 200 years found thousands of professing Christians but whose brand of Christianity was virtually unrecognisable. Kannon hadn’t simply been substituted for Mary; she had become Mary.)

In the past I have imagined Buddhist thought and practice this way. Human beings are not so much consistent individual physical entities as collections of constantly changing bundles of energy influenced by karma (the choices being made and the conditions in which that energy is operating). The task of improvement includes freeing yourself from the anchorage of the senses and the bondage of egotism. Self improvement is an intensely private journey driven by personal responsibility. Buddha was not a god. He was a man who found a/ the path to enlightenment which begins with the realisation and acknowledgement that life entails suffering. We don’t worship images or even seek comfort from them.

But I have been corrected. This is not as many others far more closely connected to the religion would have it.

The version of Buddhism established by the Japanese empire for several centuries was Shingon (‘True Word’) Buddhism. Shugendo (‘the path of training and testing’) which provides the religious flavour of the Kumano Kodo, evolved from that, as well as Shinto, animism and many other influences. But it is still described as Buddhism.

The point: these streams of Japanese Buddhism are so heavily populated by bosatsu they make the Roman Catholic Communion of Saints seem modest and responsible.

What are bosatsu? Well they are sometimes bodhisattvas, the literal interpretation, enlightened beings who have put off entering paradise in order to help others attain enlightenment or bohdi. (Sattva = ‘on the path to’). And sometimes they are not; they are entities of uncertain provenance to relate and pray to (like for example the ox at Dazaifu). I have mentioned jizu and their relative absence on the tracks of the Kumano Kodo. Here are representations to this bosatsu near an isolated temple on Shikoku and at Miyajima near Hiroshima. Hordes of them, all different, an animate universe.

Jizu are caring bosatsu. Fudo Myo-o — who in this instance just popped out of the bush near Shosan-ji temple on Shikoku — less so. A figure central to Shingon Buddhism, Fudo converts anger into salvation. The purpose of his crazed expression is to frighten people into accepting the teachings of Dainichi Buddha. He carries kurikara, the devil-subduing sword which represents wisdom cutting through ignorance, and holds a rope in his left hand to catch demons as well as to bind and focus thought. He is often seated or standing on rock because he is immovable in his faith. His aureole is typically inflamed, which according to this strain of Buddhist lore, represents the purification of the mind by the burning away of all material desires.

On the way to nearby Fragrant Root Temple we found this youkai, if not religious at least a spiritual entity.

I like to think of his, her, its name as providing an insight into the linguistic substrate of Japanese.

The word youkai is made up of the kanji characters for ‘bewitching; attractive; calamity;’ and ‘spectre; apparition; mystery; suspicious’. Now you know what a youkai is. Or do you? Written Japanese seems to me to be as fluid and allusive as public Japanese behaviour is precise, confined and measured. The kanji meanings bounce off each other like echoes in a well.

But it is the visual references that are beginning to pile up.

Senso-ji, the very famous temple in Asakusa (eastern Tokyo) is guarded by two bosatsu, Fujin the god of wind (here) and Raijin the god of thunder.

We found a version of this pair overseeing the final entry to Temple 58, Senyu-ji, on the Shikoku Pilgrimage. They belong in this company. They live in the substrate, ‘the surface or material on or from which an organism lives, grows, or obtains its nourishment’.

• • • • • • • •

And they don’t just live there as visual ornamentation, however impressive they may be in that regard. If you want to relate to them seriously they are coupled with volumes of ideas and stories and acts and edicts and directives and mysteries and frustrating contradictions.

It might be that the only successful way to live on top of that mountain of emotional and psychological cultural substrate is a life of strict discipline and obedience to very careful rule-bounded behaviour. That might also be a good way to live in congested environments where there isn’t much personal space, physical or social.

So what do you do? From this intensely rich underground, tended in some cases by trauma and neurosis, but wound tight as a drum by rule-based behaviour, in a process of sublimation you make art. But, however thoughtfully, you EXPLODE onto the canvas, the model, the board, the sculpture, the paper — in a Newtonian equal and opposite reaction. And you produce work like the examples above, surely some of the most developed, interesting and unusual art to be found in the world today.

It might also be the Japanese zeitgeist: it’s what you do, it’s what everyone else is doing, it’s what sells. But I think for many of these artists it’s what they do on a much more profound level to survive.

Yayoi Kasuma’s ‘Visionary Flowers’ in the forecourt of Matsumoto’s art gallery.

Yayoi Kasuma’s ‘Visionary Flowers’ in the forecourt of Matsumoto’s art gallery.

We got off in Tokyo, bought Pasmo cards to get around, got on a Yamanote Line train and suddenly everything fell into place. Like we’d been here before. A couple of days were spent investigating Issey Miyake’s clothes, art ancient and modern including a Caravaggio exhibition, one of those cobbled together ones where the audience was as interesting as the art. We worked our way through Yanaka and Fabric Town in Nippori, the commercial and art palaces of Roppongi Hills, the shopping malls and oddities of Odaiba, the izakaya (pubs with food) of Ueno — and marvelled again at Tokyo.

We got off in Tokyo, bought Pasmo cards to get around, got on a Yamanote Line train and suddenly everything fell into place. Like we’d been here before. A couple of days were spent investigating Issey Miyake’s clothes, art ancient and modern including a Caravaggio exhibition, one of those cobbled together ones where the audience was as interesting as the art. We worked our way through Yanaka and Fabric Town in Nippori, the commercial and art palaces of Roppongi Hills, the shopping malls and oddities of Odaiba, the izakaya (pubs with food) of Ueno — and marvelled again at Tokyo. We went east to Matsumoto (its fort is above) and spent a couple of very satisfying days there, the highlight of which was an exhibition of Yayoi Kasuma’s art at the city’s Museum of Art.

We went east to Matsumoto (its fort is above) and spent a couple of very satisfying days there, the highlight of which was an exhibition of Yayoi Kasuma’s art at the city’s Museum of Art.

It does have its Kasuma pumpkins and we did have a swim in the Inland Sea that was lovely.

It does have its Kasuma pumpkins and we did have a swim in the Inland Sea that was lovely.

Then there was

Then there was