Not Goat Island, Snapper Island, Shark Island, not Pinchgut nor Spectacle Island. It’s Cockatoo Island, the biggest island in Sydney Harbour, about 3.5 km west of the bridge: filled out to 18 hectares, carved into new shapes, three-dimensionally, from its original triangle. Great slices taken out of it for shipyards.

In the foreground of this photo is an old pump, a remnant of the island’s past — in this instance as a ship building site.

For three nights we stayed in the building on the top of this artificial cliff, what once were supervisors’ cottages, which have been refurbished for visitors.

The decks provided a wonderful albeit often rather smoky view down the Harbour.

The island has a resonant history which, as we toured, I couldn’t help but see as art.

Welcome.

Forever

The Sydney Harbour foreshore is rich in evidence of thousands of years of Aboriginal life, most evident in rock carvings and shellfish middens. But no such evidence has been found on Cockatoo Island, the Aboriginal name of which is Wareamah. The island is located at the intersection of the lands of the four tribes of the Eora nation which may provide one reason for this. But it also seems possible that the island may have been a place where women’s ritual took place, a special place not for domestic habitation. It is also possible that it was in reaction to what was observed in the 1839 Sydney Gazette: ‘It is without water and is said to abound in snakes.’

The current harbour foreshore: a jangle of tree roots, sandstone blocks natural and ashlared, remnant and contemporary infrastructure, 1950s ideas — usually rendered in concrete — about how the seaside should be, tenacious and lush sub-tropical vegetation. Patterns of both contestation and settlement, one strong line matched by another, both ferns and sandstone blocks supporting the play of light.

See what I mean? It’s art.

Convict prison 1839-69

Norfolk Island was bulging at the seams. In Tasmania Lieutenant-Governor Franklin was refusing to accept any more second-conviction convicts. ‘No place in New South Wales would be so well calculated [for an extension of prison facilities] as Cockatoo island, surrounded as it is by deep water, and yet under the very eye of authority,’ wrote Governor Gipps.

As can be customary, the execution didn’t always match the calculation.

‘Mr Inspector Lane … has paid much attention to the condition of the prisoners at night. He has often seen them at the iron gratings gasping for fresh air from without, and he “wonders how they live”. The brutalising effect on the prisoners is admitted by all, and it is described by some as terrible in depravity. Crimes of the deepest dye are committed.’ (Select Committee on Public Prisons, 1861)

There’s a silence about this image. It looks like deep breath, clear air. Your eye might be drawn by the yachts in the background or attempt (unsuccessfully) to locate the Drummoyne Pool. The implication is time past rather than any reflection on what happened here.

‘I saw Swan sitting in a recess … I thought it would be a grand opportunity for settling old scores with my tormentor. Walking quickly to where he was, I sprang at him, seized him by the two ears, and in death-like grasp, with the full strength of my powerful arms, dashed his head against the stone wall. The blood spouted in torrents from his mouth and nostrils.’ (William Derrincourt, Old Convict Days, published after long detours in 1899)

Rothko.

You can look into the blank entries to the oubliette chambers, isolation cells excavated recently after decades of disappearance, forgotten-ness in fact as well as name. These oubliettes were entered from above via a ladder which was subsequently hauled up, or you might be thrown in. No natural light. Just you and sandstone, its considerable natural attractions turning into an implacable torture.

‘From its roof I was placed in a cell, six feet by eight feet and nine feet high. As soon as the trapdoor closed I was besieged by an army of enormous rats’. In the morning not only had the rats eaten through his jacket, used as a pillow, where his food was stashed but they had also eaten the toes out of his boots.

The architecture seems to request acknowledgment of its symmetry. But it might also be a calmness onto which you can paste your own thoughts. Even though this evening the sky was celestial, the scabbling and weathering on the sandstone ensures that the symmetry is not clean, that it has character, that it prompts a response. They are gun racks (in the guardroom) and firing slits in the far wall although it is unclear where they might be aimed. But you don’t need to know. You can just appreciate the visual form.

Reform School 1871-88

In 1871 the island became an industrial school for orphaned girls and a reformatory for girls convicted of crimes. The Vernon, an aged ship, was anchored off the north-east corner as a training ship for as many as 500 orphaned boys.

‘ … Three girls came abreast of the ship, in a semi nude state, throwing stones at the windows of the workshops — blaspheming dreadfully and conducting themselves more like fiends than human beings. I was compelled to send all the boys onto the lower deck to prevent them viewing such a contaminatory exhibition.’ (The Superintendent of the Vernon to the Principal Under Secretary, 1871)

Shipyards 1913-1992

The island had been a shipyard for decades before 1913. Excavations, by convicts, often in leg irons, sometimes up to their waist in water, of the graceful slopes of Fitzroy Dock were begun in 1847 and completed in 1857.

How does this sort of thing work? (A graving dock, like a grave, right?) You drive the boat in (sail originally), shut the gate, pump the water out and then do whatever you need. Furiously maritime. In more recent years it was claimed that Cockatoo Island workers could dock a boat, clean and paint it and send it on its way in eight hours.

During the years between the reform school and the focus on shipbuilding and maintenance, the island returned to being a prison for petty criminals. However, in 1913 the Commonwealth acquired it to become the dockyards for the Royal Australian Navy. Busy during the First World War, it became frantic during the second.

- Titan Floating Crane (20 storeys high, able to lift 150 tonnes); 2. USS LST 471; 3. HMAS Australia; 4. River Hunter; 5. TSS Nairana; 6. HMAS Hobart; 7. HMAS Bataan; 8. HMAS Arunta; 9. USS Glimer; 10. HMAS Barcoo

You will also note how the island has become almost completely covered in building. Perhaps half, by area, of these buildings have now been removed leaving big aprons,

one of which (below) has become a home for fixed tents. The friends who took us there played a significant role in setting this arrangement up.

But plenty of evidence of ship-building remains. In the photos above and below are four steel plate benders so heavy and unwieldy it was decided to leave them where they were, one of the island’s many sculptural wonders.

Close at hand is the slipway, a symphony in concrete and rust industrialised by the regularity of measurement markings, made art by sea air and abandonment — an installation, a major work.

Below, a wall of the design wing, one of the monster storage rooms for patterns (pattern makers: leading edge 50s technology, even in retrospect so impressive).

Acknowledging Mondrian, but better. There’s more work and life in the colour gradients of the panels than anything he painted. So much work has gone into creating an effect of harmony. The rusty grilles balance the white form in the lower quadrant; the vent at the top and the little black door play off each other. Even the rust on the corrugated iron works. Wonderful.

More than anything else it was this that set me off thinking about the island as a gigantic art site.

But once I began I couldn’t stop. Ships … mass, scale, weight, power, size.

And just look at these. Form follows function: folders, benders, stampers, presses, guillotines. From another world. What superb pieces.

Joseph Beuys and Anselm Kiefer, eat your hearts out.

The machine room is the oldest workroom on the island. Built by convicts, again out of sandstone, it is left with some machines just sitting — creatures in steel, wildly complex but stationery, full of potential but not about to burst into life. Not without a figure present, a turner in overalls and boots with an oilcan and a big rag hanging out of his/her back pocket. Not without Kevin.

Static — but visually there is so much going on. The flavour of the way the paint is flaking off the sandstone, the soft light from the arched windows, the colours in the timber supporting the gantry, the offset of the variegated bricks in the middle of the background, the effect of the translucent but green-tinged fibre glass cladding. Suddenly those steel beams spring to life, and you become conscious that the joists above them are original: old, knotted and weathered but, as appropriate for a workshop and because of their herringbone strutting, now rarely practiced, still true and square.

A figure (thank you MM) adds a graceful sway to the squareness of the composition and the power of the gantry.

The wall to the right contains several works of abstract expressionism.

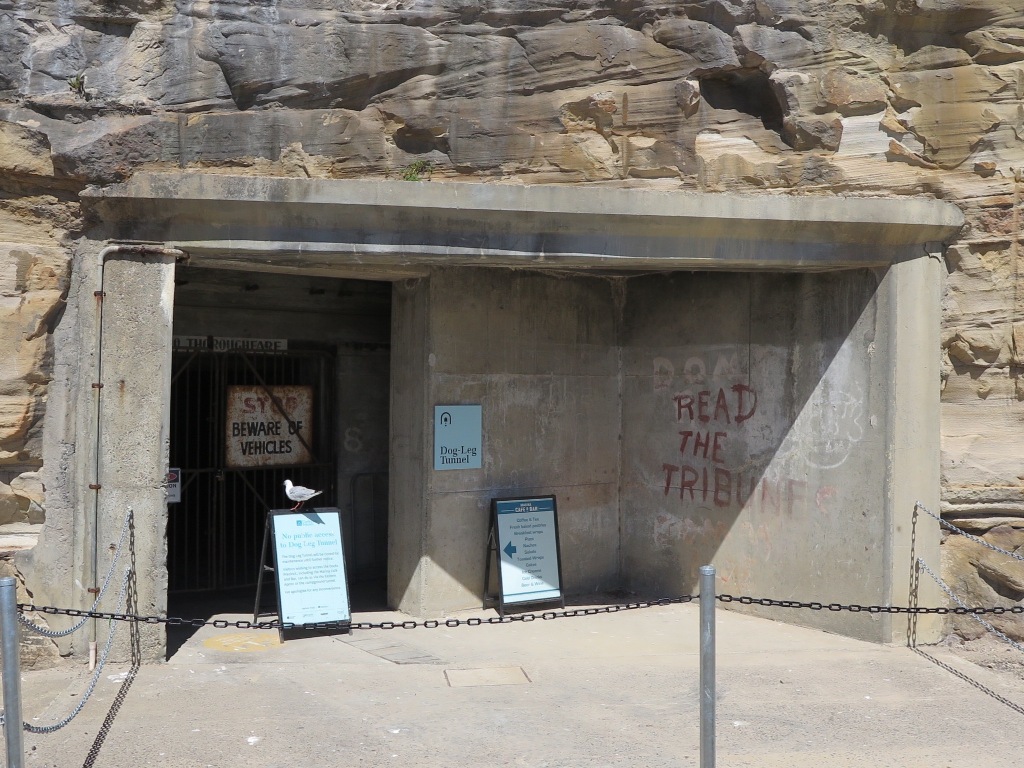

And finally a little bit of social realism: the entry to Dog-Leg Tunnel. Banksy (Very) Light.

‘The closure of the island as an operational dockyard was one of those events in the life of a city of region that signals the end of an era. For many it was a jolt to realise that an industrial site had run its course. The fraternity of Cockatoo Island workers and their families, generations of tradesmen, naval architects and administrators, felt the loss most acutely. They understood the depth of experience, knowledge and hard work that had been invested in the dockyard, the decades of achievement that had contributed to Australia’s economy and naval preparedness. They understood too, how easily this great legacy might slip from view.’

This comes from a history of Cockatoo Island from which I’ve borrowed heavily. The legacy is still there, if not in full view, readily accessible — made far more so by the efforts of the Sydney Harbour Trust and its hospitable and helpful employees. The island hosts concerts, art exhibitions, school excursions, film making, parties, openings and closings. It seems to me it’s going just fine.

If there is a niggle of concern it would be about the fortunes of the hundreds of tradesmen and, by the time of closure, tradeswomen, and apprentices and their knowledge and skills. This country sometimes seems just so willing to sell off capacity to make things. Maybe they’ve been absorbed into the shipyards of the present and future. I hope so.

We left the island having had an exceptionally good time, and because it’s an island we left by boat just as we had arrived. One of the key points I guess is that it is a maritime experience, foreign to but delightful for landlubbers like me. You take the ferry from Cockatoo Island to Circular Quay. Camera pointed, I continued with the idea of encounters with art.

A repeat pattern — regularity — suggestive of endless shoe boxes, set off by life boats with a ‘safe’ Hi-Viz roof along with decorative ribboned ‘handles’ of rope for floundering souls to grasp. Secure hatches and guaranteed flotation regardless of the size of the seas. It mightn’t be exciting, but it is orderly and secure. The Titanic, but so very safe.

It turns out that this ship is Ovation of the Seas, the ship from which on December 9th last year a party disembarked to visit Whakaari also known as White Island, just off the coast of New Zealand.