He’ll laugh. Technically a pretty disgusting photo, but pink eye and all it’s caught something. Swervyn Mervyn, the Bishop of Dubbo. Magician. Showman. All Star. Champion.

And now there’s a book about him.

• • • • • • • • •

Wikipedia’s item ‘List of photographs considered the most important’ has several hundred entries.

They range: the first recorded photograph (View from the Window at Le Gras); Isambard Brunel standing in front of his mighty chains; American landscapes; the first X-ray photo; the negative which indicates that The Shroud of Turin actually contains a photo of Christ; the first digital photo; the first photo uploaded to social media. Earthquakes, cataclysms of many sorts, portraits, sports events (Mohammed Ali standing over a prostrate Sonny Liston), moments in the tectonics of history, oddities and the conditions of humankind, including suffragette Emily Davison being trampled to death by King George’s horse, Anmer.

Among these hundreds, Australia has one contribution. And it is this.

Merv had been manning the Dept of Aboriginal Affairs’ stand at Brisbane’s Ekka (Agricultural show) when he got a call because something big might be taking place at Wattie Creek. In Mt Isa while the plane was refuelling he happened on Keith Barlow, another photographer mate working at the time for the Australian Women’s Weekly. Barlow and his journalist colleague Kay Keavney became intrigued by this adventure of Merv’s and decided to tag along. Merv would have been hazy about what was happening as well as a bit excited. Eyelids batting up and down, huge grin that might turn into a grimace, sucking his teeth: what’s he doing? you’d think. What’s he up to? It’s not every day you go to Wattie Creek, not for any reason — it’s a bit out of the way, in the desert, about 550 kms south of Darwin — but, you know, could be promising. Could be anything. At least I’ll see what the bugger’s up to.

Whitlam’s government had negotiated the return of a portion of Gurindji land in the form of a pastoral lease — not a big deal in the scheme of things, but the beginning of something much more consequential. 16 August 1975 was nominated as the ceremonial handover. The speeches were made under a shelter constructed from tree boughs and canvas. It’s there in the background.

Gough said, inter alia: ‘I want to give you back formally, in Aboriginal and Australian law, ownership of this land of your fathers. And I put into your hand this piece of the earth itself as a sign that we restore them to you and your children forever’, and strained some of that very red desert sand from his hand into Vincent Lingiari’s.

This is a sliver of Vincent’s reply, translated from the Gurindji, and worth recording not least for its remarkable generosity of spirit. ‘We want to live in a better way together, Aboriginal and White men, let us not fight over anything. Let’s be mates.‘

This was all happening under the shade of the lean-to, hopeless for a photo. All shade, no definition … you wouldn’t even see the sand. ‘Mervyn said he looked at Barlow and they both grimaced.’ Merv to Whitlam — nothing should stand in the way of a good pic — ‘Mr Whitlam would you mind if we do this picture again outside in the sunshine?’ That’s Merv. When it comes to business, all business. He lowers his voice, and his chin, when he gets to this point in the story, and does his Whitlam. ‘Certainly Mervyn.’ Barlow held the other photographers off taking his turn only after Merv had finished. ‘I crouched low to include a good portion of sky. … I imagined using it on the cover of a magazine. I wanted to leave room for a masthead, National Geographic or Life or whatever.’

I’ve heard this story many times but I’m thieving here from The Book, and its author Tim Dobbyn notes that there were at least four other photographers there that day. They got the pic too, or versions of it; but, Tim says, they didn’t get the sky. Have another look. How important is that sky. And the dominance of the two figures in what would have been a helter-skelter scene with all sorts of things going on. The little cone of sand is in Vincent’s hand. Merv did get the picture. History was made.

But not for more than a decade, and it nearly didn’t happen. Read the book (pp. 104-105) and discover the role that Paul Kelly and Kev Carmody played in its re-discovery and how from little things big things can grow.

• • • • • • • • •

That’s not his best pic. There are others. The book says more than 50,000.

This is one of his favourites.

Cousins, Ralph and Jim. Brewarrina. 1966. Two lads skiving off from school rowing down the Barwon near Gundawera Station. The joy of life. (Where’s the photographer? Yes of course, in the boat too. You forgot that didn’t you.)

• • • • • • • • •

On an appallingly hot day I flew to Sydney from the Sunshine Coast to attend the book’s launch. I did feel I needed to be there. Because of the heat and the excitement of seeing friends I hadn’t seen for a long time it was a slightly out-of-body experience. I’m not sure the book shop staff managing the occasion did it justice: too sweaty, too rushed, too keen to get home, insufficiently respectful to what I think is a great work.

Another one in Canberra followed, then Melbourne. By Melbourne the 80 year-old maestro was a bit puffed and in his absence I was invited to add just a little colour and movement to the event. What follows is something like I said.

• • • • • • • • •

I am David McRae and I have a bit part in this book. Merv and I spent eight months on a project wandering around Australia together and became fast friends.

We are surrounded here [the Avenue Bookstore in Elsternwick] by thousands of books, perhaps tens of thousands. I want to give you three reasons why this particular book is unique among them. Not a bit unique, or possibly unique or unique on Thursdays. ‘Unique’ as per the Oxford Standard Dictionary definition. One of a kind. Out on its own. Exceptional.

The first reason is that it contains 74 photographs. 18 of them are of Merv. He’d like that. He’s always been a handsome boy with a wicked glint in his eye. 8 others provide complementary context and illustrate just how assiduous Tim has been in the preparation of the book.

And 48 of them have been taken by Mervyn George Bishop. I note here incidentally that only one is of Gough Whitlam and Vince Lingiari.

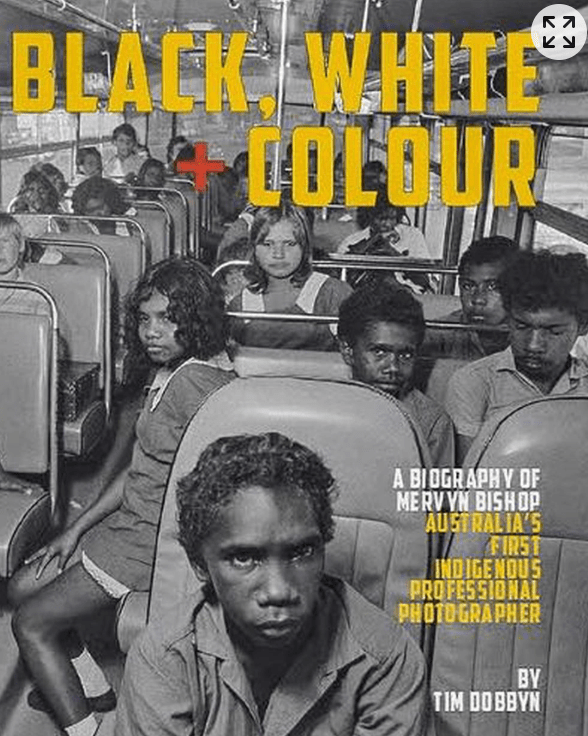

Merv is not a good photographer; he is a great photographer. Technically he is hugely proficient. But his great photos, and there is one on the book’s cover, are as good as anyone’s. And I do mean anyone’s. Very seriously, he is properly in a list with Annie Leibovitz, Steve McCurry, Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams, et al. It is a lovely irony that his photo of Cecil Beaton is included in the book.

Why are they so good? Partly because he takes so many. He’s got a lot to pick from. You and I breathe: Merv takes photos. And has done since he was 12. His camera is an extension of his arm. Curating his archive would be, and has been, the work of the world.

But he’s also got what we have to call an ‘eye’. Famously he asked Gough and Vince to repeat the sand pouring moving them outdoors so the picture could be at its absolute best. He composes his pics as naturally as his son dances and his daughter smiles. It’s just there. Innate.

And tellingly, he has had access to places and contexts that very few other people have. It is possible that Merv has been to more of Australia than anyone else ever. I’m thinking here of the requirements of his work for the Dept of Aboriginal Affairs, an unsurpassed record of Black Australia at a particular point in time (which he would say was an opportunity not sufficiently exploited). And then the later work for various purposes of which the Burnt Bridge photos in the book are indelible examples.

48 Mervyn Bishops. A tiny slice of his output, … but what a slice.

[You can if you wish CLICK HERE to take you to a discussion generated by thinking about what makes a photo great.]

The second reason. This is a book about a great artist by someone who is not only also a very fine artist but a lifetime close friend of the great artist. This never happens. You can be a friend, or you can be a biographer, but simply from circumstance never both. It just doesn’t happen. Biographers can be sympathetic or insightful but they are never friends. (The only other possible case I can think of is Best Minds by Jonathan Rosen, another fine book as it happens, in which the friend ends up as a psychotic killer. This is not the case here.)

Read the first chapter, which is something of a masterpiece: two friends on a knockabout adventure wandering round the western plains of New South Wales. Merv’s making his jokes and cackling at his own great humour. But nonetheless he makes sure they visit Fred Hollows’ grave in Bourke. There’ll be a day’s itinerary but Merv will decide that he wants to go and see something that he might or might not remember and ends up doing an ironic little shake-a-leg dance clanging two rail spikes together before heading off to a Bowlo for the night’s tucker and a beer, saying gday to everyone but probably knowing half of the assembled throng, them or their ‘lations.

Only a friend could get Merv so right, and, far more pertinently, only a very good friend would have permission to get Merv so right. Because Merv is a big dag. And of course, the book leaps into life as a result. So honestly correct, so fair dinkum. We are reminded that this great photographer is also a human being, an incredibly interesting and likable human being, who has nonetheless ridden some rough roads.

But such a capable pair this writer and this photographer.

The book is meticulously researched. Some would say perhaps over-researched. Via its preparation I discovered that something I had always believed to be true — the product of our work together had won an international prize — was fiction. Almost certainly over-researched in some regards.

But it is also written with the ease and precision that only a lifetime in journalism can generate. It is such an easy read. So detailed, so smooth. As a fellow writer I can also say, and such a shitload of work.

That’s two reasons. They may have been obvious. There is a third that might be less so.

It is a book about Black Australia that you never read.

Not Alexis Wright, not Tyson Yunkaporta, not Melissa Lucashenko. And certainly not Bruce Pascoe. No dizzying cosmology, no complex moiety patterns, no tjukurrpa — something different, can I say again — unique. This is a book embedded in a Black Australia that doesn’t have a literature.

The last census told us that just under one million Australians identify as Indigenous. Quite a lot. What do we know about that million?

Here are a few things. Some are eminent and well known. Some, maybe five percent, are wealthy and live very much like other wealthy Australians.

About 15 percent live in remote Australia, about half of those living in very remote communities. This is the location of The Gap that never closes and, while they live there, this is likely to remain the case.

But that leaves 80 percent. And that’s where this book is located.

The 80 percent. They live in Australian towns and cities. If you follow the Newell Highway from Echuca through to Brisbane, you’ll pass somewhere near the homes of a couple of hundred thousand blackfellas. Throw in Rocky, Bundaberg, Townsville, Cairns and Perth and there’ll be a lot more.

These are people with jobs, families who send their kids to school in uniforms, who shop at the supermarket, who have footy teams they barrack for, who enjoy a barbecue, and pavlova and French cakes, who might be ambitious or relaxed, whose lives go up and down a bit like everyone else’s.

But there is more. There’s always more. And when you read the book you will understand that there is more.

Some things perhaps you might expect, but there are others that will almost definitely surprise you. You might jump a bit at the challenge to some of the stereotypes of your settled thinking, and be reminded of the complexity of the elements from which our lives are constructed. You might also think about the warp and weft of culture, in plural form, the magic of its assembly and the extraordinary variety of its products.

Case in point: Mervyn Bishop. Living in Oatley, almost but not quite in ‘The Shire’, home of Scott Morrison and his ilk. Happy family. Suburban, maybe a bit Uptown, a bit Flash Blak. Asked in his job interview for the DAA if he knew any Aboriginal people.

On the other hand, First Aboriginal This First Aboriginal That. Blah blah blah. Somehow it is never not a question.

And that’s the third thing that makes this book unique. It’s not called Black, White and Colour for nothing.

[You can if you wish CLICK HERE to take you to some further thoughts about cultural construction.]

I think in accord with his wishes, I would say that Merv’s not a great Aboriginal photographer. He’s just a great photographer. And what’s he like? Like no one so much as Mervyn George Bishop, and what an interesting person!

And great work Tim to have rendered all this with such care, thought and skill.

I’ve missed Christmas, but BUY THE BOOK. [That’s a live link. You can go straight there.] Tell others about it.