The subtitle of Black, White + Colour is ‘A Biography of Mervyn Bishop Australia’s First Indigenous Professional Photographer’. And of course that’s true, important and commercially sensible to bill the book that way. But its contents provide a more complex if still wonderfully coherent account of what it is to be Merv and the contexts and events which have helped shape him. In my related blog I’ve referred to this as ‘the warp and weft of culture, in plural form, the magic of its assembly and the extraordinary variety of its products.’

I’m particularly interested in this because it has provided a lesson I have had to learn myself, many times and sometimes to my cost.

Naturally you must read the book for a proper account of Merv’s world. (Off you go and buy it. HERE.) Treat this as a taster with a slight twist of emphasis.

• • • • • • • •

HOME

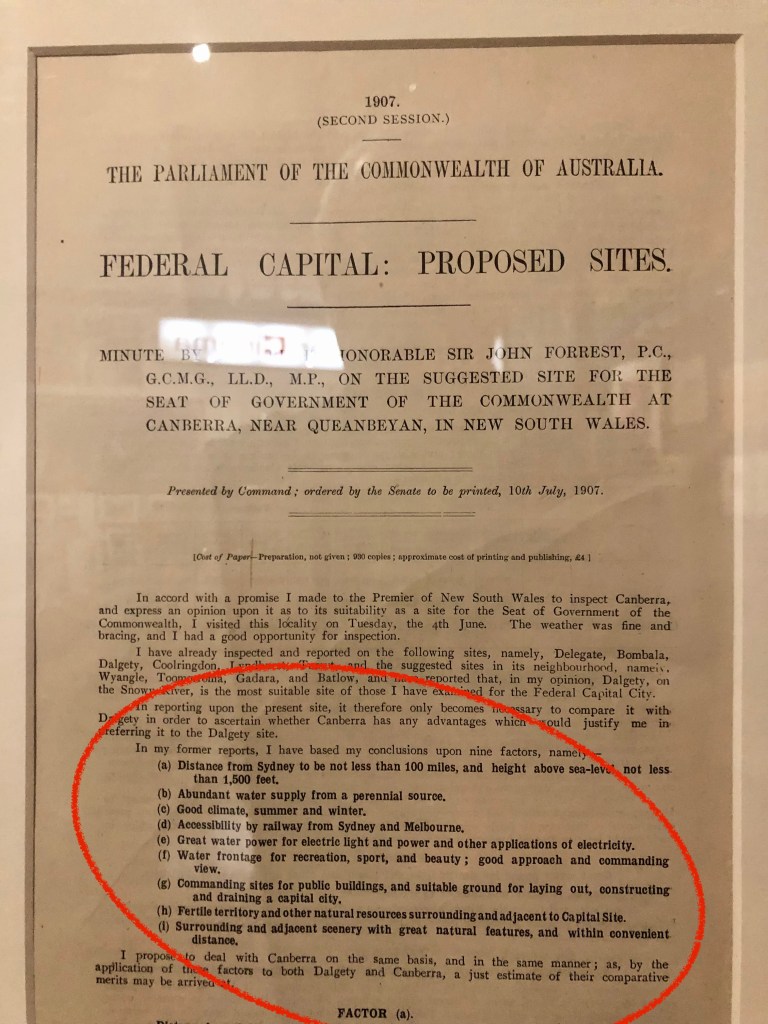

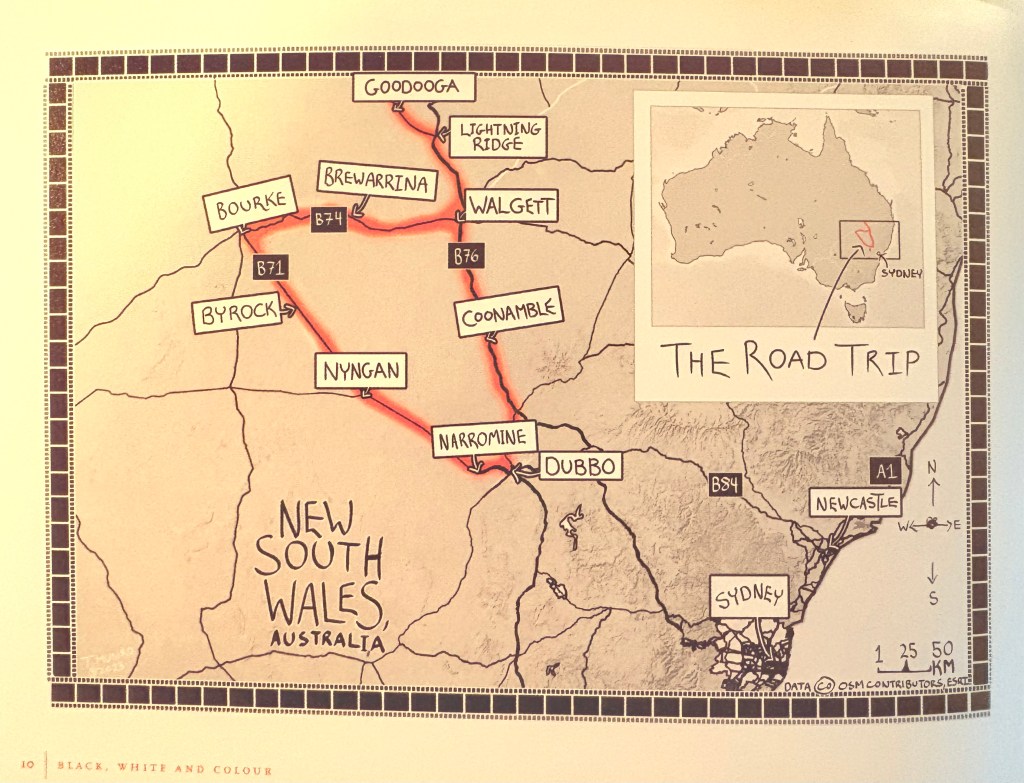

This is the map from the book which describes the road trip Tim and Merv took together to help prepare it, revisiting old stamping grounds and relations, the sites of some of his photographs, RSL and Bowling Clubs — landmarks of north-western NSW, a very special, interesting and not much visited part of Australia. The grey nomads pull in at Goodooga’s springs and might buy an opal or two at The Ridge, but they’ll whip past the steel shutters of Walgett and not spend too much time at Bourke. Byrock’s population is 50. Maybe. It used to be the case that one of them would be a teacher.

This is remote country, and the distances between settled points can seem vast, in fact it might seem that no one lives here, but that would be quite wrong.

Merv was born in Brewarrina (known to anyone who knows it as ‘Bre’, pron. ‘bree’). The Barwon, which when joined with the Culgoa becomes the Darling, teeters along between Walgett and Bourke in great whorls now often barely damp. Bre is half way. Above Walgett the cotton farmers have stripped out the rivers’ flow. When they were left wild this stretch of the Darling was home to an important paddle steamer trade. At Bourke you can still visit the wharf where the steamers used to tie up, now usually 10-15 metres above water level. The Wandering Jew was one of the last to operate. It caught fire at Bre in 1914 and sank.

150 years ago Bre became a hub for that commerce. It had a bank, a courthouse, two hotels, two stores, a regional administrative office, a school. Today it has a population of about 800, from some points of view 30 fairly sparsely settled blocks in the middle of nowhere, but big enough for a swimming pool and a Catholic primary school as well as a government one. Leo Schofield was born here in 1935. His father was one of the publicans.

And it has its fish traps, Bhiamie’s Ngunnhu, Bhiamie being the creator figure of this region’s mythos.

Most of the straight-line barrier in the photo is a comparatively modern contribution. The rest could be 40,000 years old which would make these traps one of the oldest human constructions in the world. That’s the claim. But there is no doubt that the river and its traps — already a fluid junction of several First Nations groups: the Ngemba Weilwan, the Murrawarri and the Yuwaalaraay — would have been major drawcards for festivities, food gathering and other forms of socialising for the dozens of clans spread through what today we think of as northern NSW. A mix of peoples.

In 1886 the Aborigines Protection Association established a mission near Bre on a reserve of 5,000 acres 10 miles east of the town and on the opposite bank of the Barwon. The very first mission in New South Wales, it kept operating until 1966. If you want to know a bit about what it was like [in 1954] you can read Dr. Ruth Latukefu’s recollections here.

The mission was established initially to deal with/ accommodate/ respond to the number of Aboriginal people camping round Bre and their ‘intemperate behaviour’. It soon became marshalling yards for the problems (and non-problems; just sent, or taken) drawn from an area ranging from Tibooburra, 10 hours drive west from Bre today, to Cobar and Lightning Ridge, half the distance in different directions. The mission was — not my term but a Royal Commission’s — ‘an enforced concentration of Aboriginal people’, a concentration camp. And in that camp were ‘Aboriginal’ people, or ‘Indigenous’ people, or ‘First Nations’ people. But whatever you want to call them, it is a bit like saying ‘European’. They had different languages, different cultures and lore, and different Countries none of which were at Bre. They didn’t always get on. Why would they? A mix of peoples.

Bre was also home to some of the powerhouses of the Aboriginal world. Essie Coffey might be the best known, but Steve Gordon and Tombo Waters lived there as well. Big names, strong leaders of renown. Part of the mix of peoples.

One of my own Bre stories is a memory of giving a talk to the staff at the school where at the time Michael Chamberlain, post-Azaria, was teaching. If he lifted his head once from his newspaper during the time I was speaking I didn’t notice, suggesting that as well as unwonted celebrity he was a man of keen judgment. Part of the mix. Places may be small but they are not without characters.

• • • • • • • • •

Mervyn’s father Minty was the lovechild of a travelling [Punjabi] merchant, Baroo Fazldeen, and Mervyn’s grandmother, Suzannah McCauley Bishop. Suzannah’s mother is listed as Aboriginal in her marriage certificate to Robert Bishop of Melton Mowbray, England. Her father is identified as a labourer named John McCauley, likely an Irishman according to family DNA results. On Mervyn’s maternal side there is a similar pattern of Aboriginal women and White men. (p. 24)

Such ancestries are not uncommon in parts of Australia, especially where there were disproportionate numbers of White men and White women.

• • • • • • • • •

Merv’s mother, a woman who wore a hat when she went out, had a camera, a Brownie Box which Merv started using at 11. He bought a camera of his own when he was 12.

‘We were uptown Blacks’, Merv says. ‘We knew we were kind of special but we didn’t chuck it around saying “We’ve got this” or “We’ve got that”. We would have got a slap.’ But, nonetheless, ‘I think we [Merv and his sister Cynthia] missed a lot of the stuff the other kids copped, racism stuff in town.’ (p. 40, 41)

SCHOOL

Mervyn did well at school in Brewarrina despite a full plate of other interests. ‘Margo Collins and I used to run neck-and-neck for the top of the class,’ said Mervyn. ‘If I came first, I’d get five pounds from dad and if she came first she’d get five pounds from her stepdad. They used to bet on us.’ (p. 51)

But when Merv was a student there Bre Central topped-out at Year 9. After that for Aboriginal boys the trades were an unpredictable possibility, for girls domestic service might have been feasible. For smarties and if you got a leg up, a bank or an office job might be available.

Both Merv’s mother and father were ambitious for him. But it was the interest of the vicar of the local Anglican church where Merv was an altar boy which might have been decisive. At the age of 14 he was sent off to the Holy Trinity Boys Hostel in Dubbo so he could attend the local public high school. Bits of money were put together from various sources — including the efforts of the Dobbyn family — to find the £60 per term boarding fee plus the other costs associated with going to school. He had two mates there from Bre, but of the 60 boarders he was the only Aboriginal kid.

At 14. Late morning on your own catching the steam train from Bre to Byrock. With some patience that would hook you up with the daily diesel from Bourke to Dubbo where you’d arrive in the early evening, home a day away … already an adventure and you hadn’t even started.

And Dubbo: Queen of the Western Plains, with a river and a zoo. Population in June 2021: 43,516, of whom an unusually high 86 per cent (including Glenn McGrath, various famous rugby league players and Dave Mason and the rest of The Reels) had been born in Australia.

Dubbo is on Wiradjuri Country, and at the census 16 per cent of the town’s population described themselves as Aboriginal. In summer that proportion rises as folk come down from the river towns further north to get out of the heat. This is not always to everyone’s taste including that of the local Aboriginal population.

The first two public buildings erected in Dubbo were the police station and the gaol. The Old Gaol remains a major tourist attraction, ‘an appealing oasis in the midst of the Dubbo CBD’ to quote the brochure. Eight men were hanged in its courtyard: a Dane, two Chinese, three Irishmen and two Aboriginal people. A mixture. ‘Rolf Boldrewood’ (in fact Thomas Alexander Browne) wrote Robbery Under Arms while he was Clerk of Courts there.

When I was a regular visitor you could get excellent coffee at Scotty’s in the main drag. It may now be Ha Noi Corner. The Hog’s Breath Cafe where I mistakenly ate once, and I think once only, closed in 2021. It’s the same sort of muddle of cultural influences, borrowings and exchanges that can surprise you in a middle-sized rural centre.

• • • • • • • • •

Merv ‘went into some sort of meltdown’ in his Leaving (11th and final year) exams and failed four of his six subjects missing out on the prospect of a job with the ABC. He went home to Bre.

WORK

He got a break.

Early the year after he left school he was offered a job at the ABC in Sydney, “a general dogsbody” sort of job. Not quite out of the blue, but a pleasant surprise nonetheless. Three months later, bored, he applied for a job as a photographer at the Sydney Morning Herald and got it. Subsequently he had some formal training in a part-time course at the Sydney Tech. Tim Dobbyn, the author, quotes Harry Millen who originated, devised and taught the course as saying, ‘It was most strange to have an Aboriginal in the class.‘ As might be assumed, his work took him to all sorts of places including to the social pages. On page 76 of the book there is evidence that Merv has been snapping at a cocktail party in Rose Bay. The women in the pic look like they may also be thinking, ‘It is most strange to have an Aboriginal in our lounge room.’

Merv had been a prefect. He wouldn’t have cared. He would have giggled about it later as he produced a delightfully embroidered recount.

A colleague at the Herald: “None of us ever thought of him as Aboriginal . … there was a real camaraderie there.” (p.77) This somewhat ambiguous quote is paired with a ho ho story that turns up everywhere in Blackfellaland. In the darkroom — “Hey Bishop, are you there? Are you there Merv Bishop? Smile so we can see you.” Dominance is sometimes spectacularly unaware. And dumb. And wet.

Like run-ins with the police on the basis that he was the Blackfella in a group who were otherwise White; or the continued occasional refusal of service in a bar. And it could turn around. I don’t know that he could count the number of times he has been called a ‘coconut’ or similar. (‘Coconut’? Black on the outside, White on the inside.)

Eight years after beginning at the Herald he took ‘Life and Death Dash’ (see below) the photo which won him the Press Photographer of the Year Award. Mervyn was a C-Grade [pay grade] photographer when he took the award-winning photo and would be a C-Grade photographer when he left three years later in 1974. … Even absent the contest win, it seems incredible that Mervyn would not progress to at least a B-Grade level by 1974. “There was a glass ceiling for Aboriginal photographer Mervyn Bishop at the Herald,” Merv said. (p. 87) Later Tracey Moffat asked him why he didn’t stack on a turn. “I had to maintain a sense of propriety in the hope that maybe other Aboriginal people would be able to gain employment there as well.” (p. 89) I had entered the assimilated world of the White institution. There were very few Aboriginal people in any profession and hardly any that I could share my experience with in Sydney. My Aboriginality was in different places, but there was no place for it at the Herald. (p. 188)

He left, and applied for a job as a liaison officer with the newly established federal Department of Aboriginal Affairs. The interviewers were concerned about whether he could relate sufficiently to Aboriginal people living on reserves and in impoverished communities. “Have you had much to do with Aboriginals? Mervyn recalls being asked. (p. 91) Eventually he was employed as a low-paid clerical assistant to take photographs.

During these years he had married Elizabeth Johnston whose mother believed her English ancestry could be traced back to the days of the Magna Carta. She asked Merv one day how much money it would take for him to walk away.

ART

The thing is, Mervyn was never in the art world, he was a photojournalist. (Tess Allas, art curator and champion of his successful nomination for the Red Ochre Award for a lifetime achievement in the arts by an Indigenous person. p. 150)

The ’80s for Merv were a period of mooching round between different jobs, a number of which were tenuously associated with education. He began hanging round Tranby College, ‘a space [in Glebe, very inner Sydney] for Mob to gather, share stories, and gain further skills and knowledge through community programs, events and accredited training’. He needed the use of a darkroom for a project he was working on, and of course he would start chatting because that’s what he does. Merv is a world-class chatter. He and Andrew Dewdney, an English academic who was working at Tranby at the time and who had become a mate, were putting up an exhibition of student work in a shopping centre. One of the panels included a print of the Whitlam/ Lingiari photo. Merv said, ‘That’s my photo,’ He wasn’t upset about it being used. It was more pride. (p. 120)

Dewdney … argues that the Tranby experience enabled Mervyn to look back on his archive and reassess his own work and heritage. ‘He could look at that collection not merely as Joe Photographer but as an Aboriginal photographer.’ (p. 130) ‘[Tranby’, Dewdney says] ‘was where he was challenged around his cultural heritage and Aboriginality.’ (p.119)

His first major show was ‘In Dreams’ in 1991 at Sydney’s Australian Centre for Photography. Tracey Moffat was asked to curate it. ‘I thought I have only seen this one great image of his. But [when she started digging through all the material at Merv’s home at Oatley] I found this treasure trove of images.‘ (p. 131)

The show opened the day his wife died. Tim [Bishop, Merv’s son] said the ACP was packed that night and if you hadn’t known his mother had died that afternoon you wouldn’t have caught on. ‘I truly think that some people have a calling, and one of Dad’s cards that he plays so well is that of a showman … to this day I don’t know how he was able to do it. ‘ (p.133)

‘In Dreams’ toured 17 Australian venues and went to England. ‘So much of becoming known as a photographer has to do with being established within the history of photography. This means getting your work seen in an exhibition, and, more importantly, being published as well written about.’ Sandy Edwards reviewing the exhibition in Filmnews. (p. 135)

There were some more landmarks along the way, including some international recognition and a solo exhibition at the AGNSW. But two others stand out vividly.

The first was in concert with the NSW State Records office. Susan Charlton, its Creative Producer, recognised this image as one which was also held by the Records Office during one of the more exotic turns of events in Merv’s life: his story, illustrated, at the Sydney Opera House with him narrating. William Yang, Chinese-Australian artist, with his hand on the wheel.

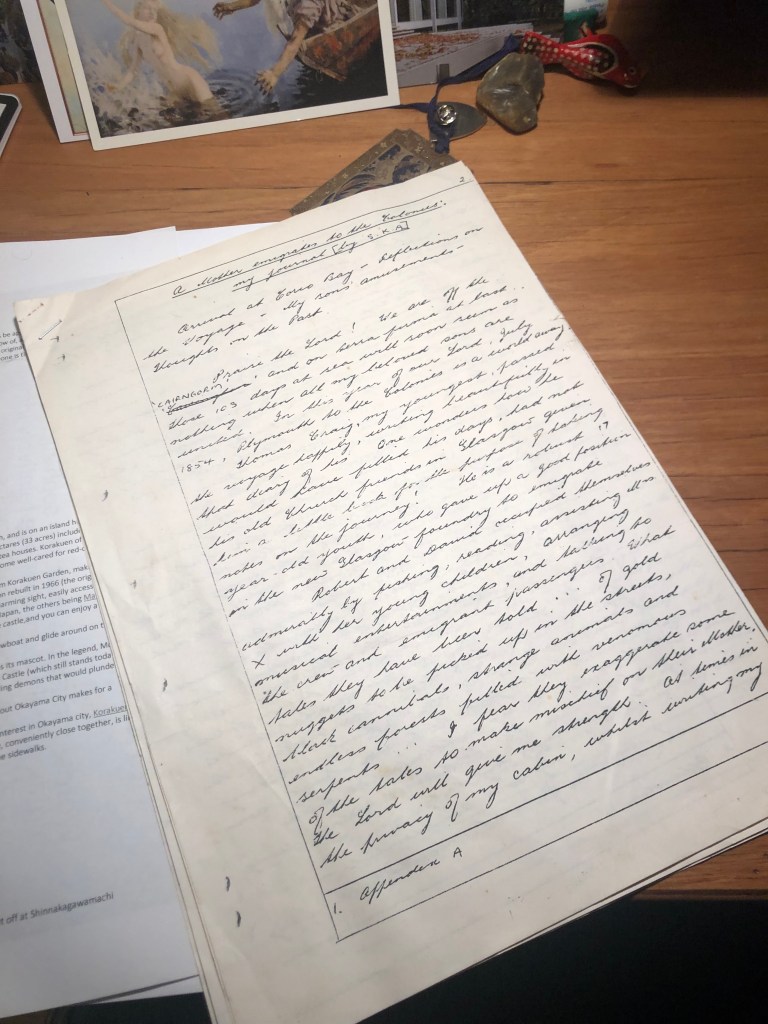

This is Merv’s maternal grandparents plus flowergirls on their wedding day at Angledool in 1925, colourised and with birds inserted.

The Records office had 1000 images which had been collected over the years from the Aboriginal Welfare Board which they wanted to develop into an exhibition.

This was the mission: ‘Though the policies of successive governments aimed to dismantle their culture, Aboriginal people have always found ways to reunite with family and community and to create contemporary links to their culture. Today the Board’s written records and photographs are valuable for the leads and clues they may provide to help in this process, creating a new purpose and place for the photographs within contemporary Aboriginal life.

‘Decades after the photographs were taken, they still produce mixed emotions for Indigenous viewers — from the delight of seeing rare evidence of community and culture to the sad reminder of loss and separation. Because of these sensitivities, the entire exhibition process involved the consent, advice and support of many strands of the Indigenous community, including the NSW Department of Aboriginal Affairs for guidance and protocols; an advisory group for ongoing input and support; and the approval and contribution of individuals and communities represented in the Board’s photos.’ (From the catalogue which can, and should, be viewed HERE.)

But the real stroke of genius was to have Merv along not just to take photos at this extremely popular and important activity (over two years visiting 17 regional centres), but to just be himself, greeting, introducing, facilitating. What a VERY good idea.

The second was a commission to take portraits of 22 of Sydney’s Aboriginal Elders for the Australian Museum. ‘I always think: Do a picture that they would like as much as me.‘ (The Bishop Theory of Art, p. 176) And this proved to be the case. Here they are: huge, but warm, relaxed, comfortable, feeling at their best, representatives of a living vibrant culture.

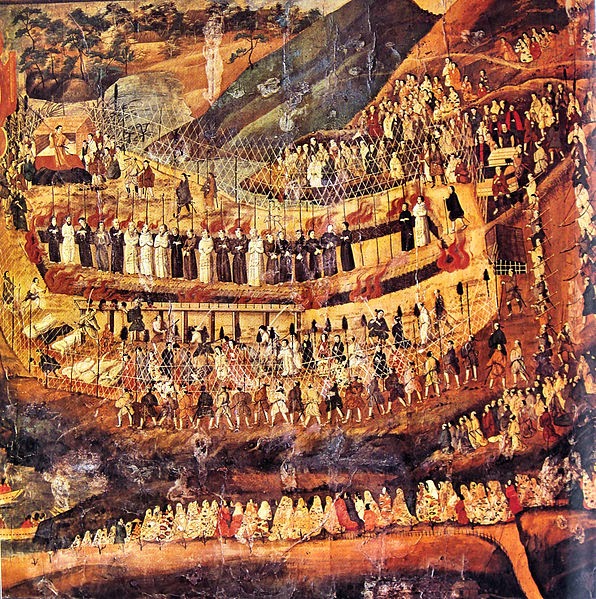

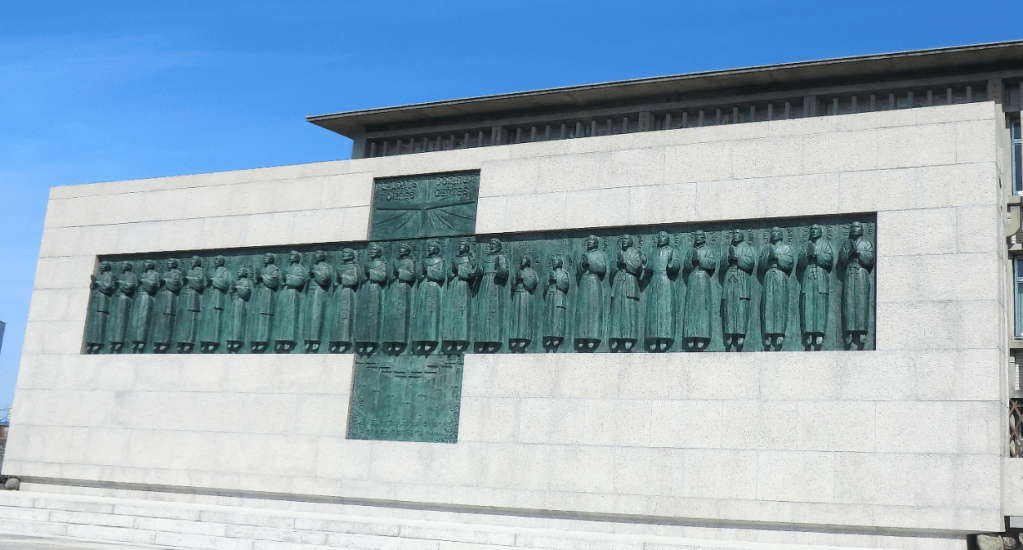

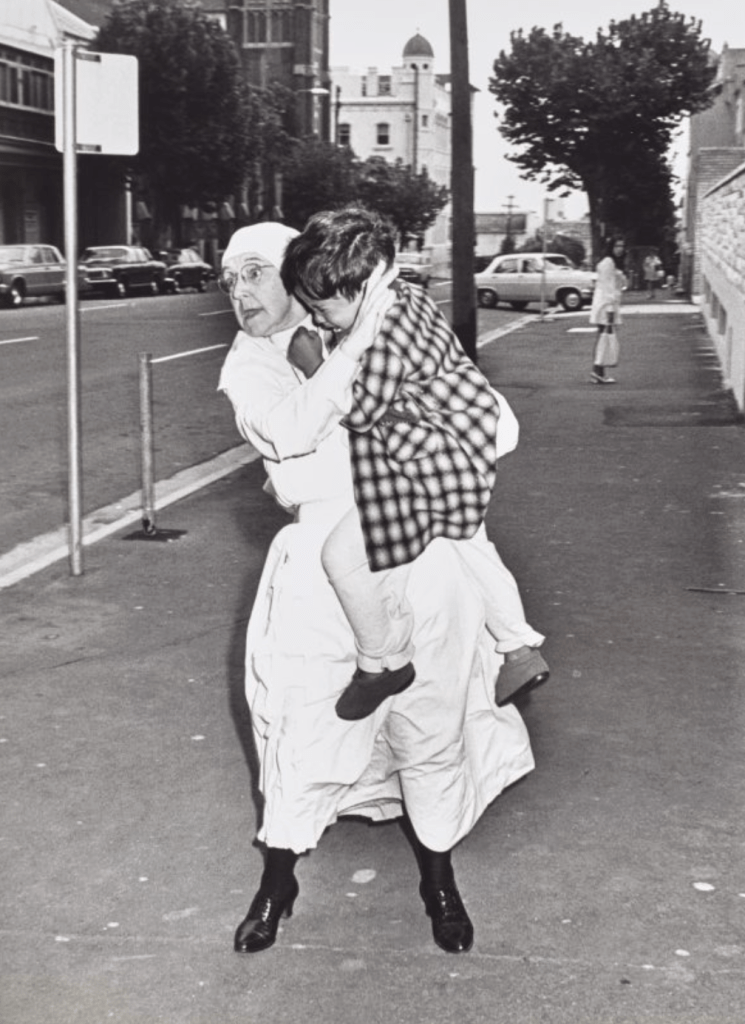

‘In this startling image, composition, contrast, and Aboriginal social commentary combine. It is a classic example of photojournalism that has since transgressed its original context and come to insinuate the impact of religious missions within Aboriginal Australia and, in particular, on the Stolen Generations.’ AGNSW art note

Merv: ‘There was only one Blackfella there that day and he was behind the camera.’

THE BARRICADES

‘Mervyn didn’t charge the barricades,’ [Hetti Perkins, a distinguished art gallerist says.] ‘Instead he went under or around them to get where he needed to be.’ (p. 200)

Mervyn’s story is … a caution against easy assumptions at a time when race and racism occupy large swathes of public discourse. He cut his own path, defying at times the expectations of both White and Aboriginal people. Mervyn is often celebrated as a chronicler of Indigenous Australians but sees his body of work as much broader. He resists drawing too large a message from his life and his images, yet he inescapably stands as an Australian treasure. (Tim Dobbyn, the author, p. 9)