World pre-history has no parallels even remotely comparable in age or skill [to these paintings]. Truly the Bradshaw artists were the Ice Age’s Michelangelos.

— historian Ian Wilson, Lost World of the Kimberley

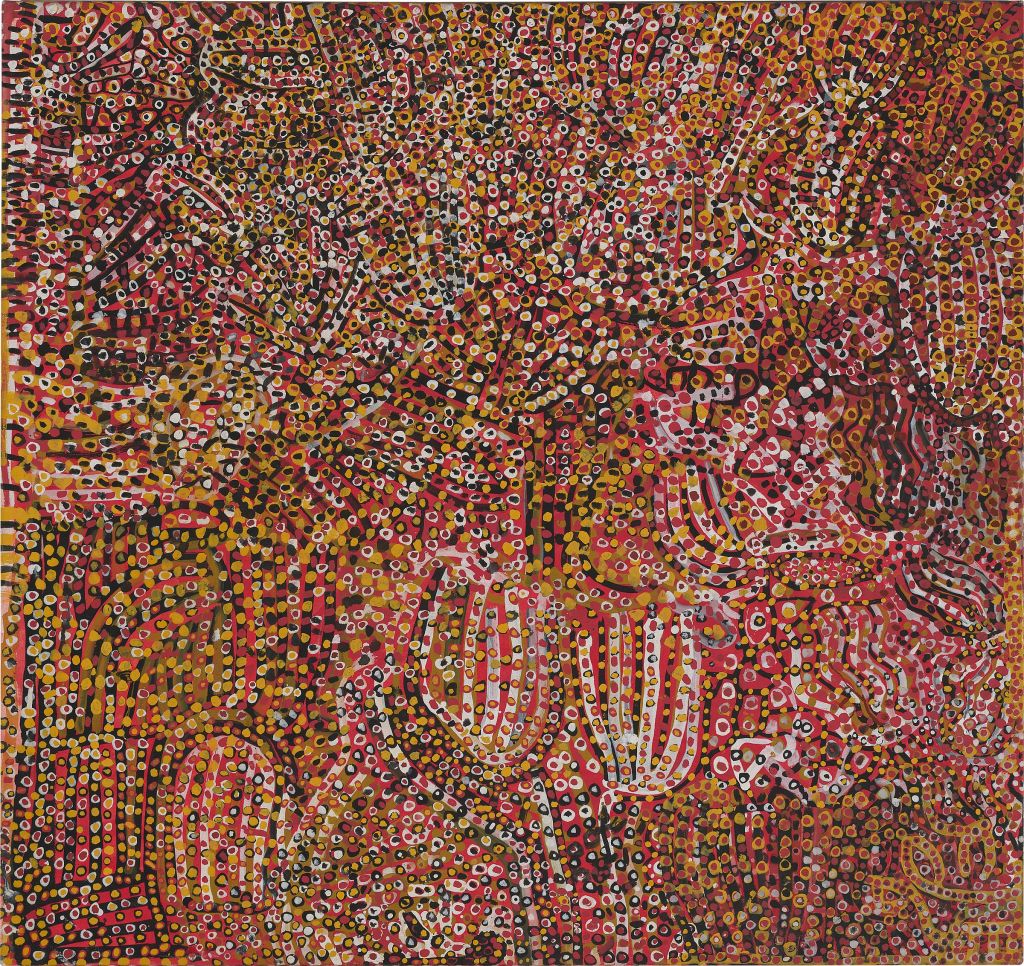

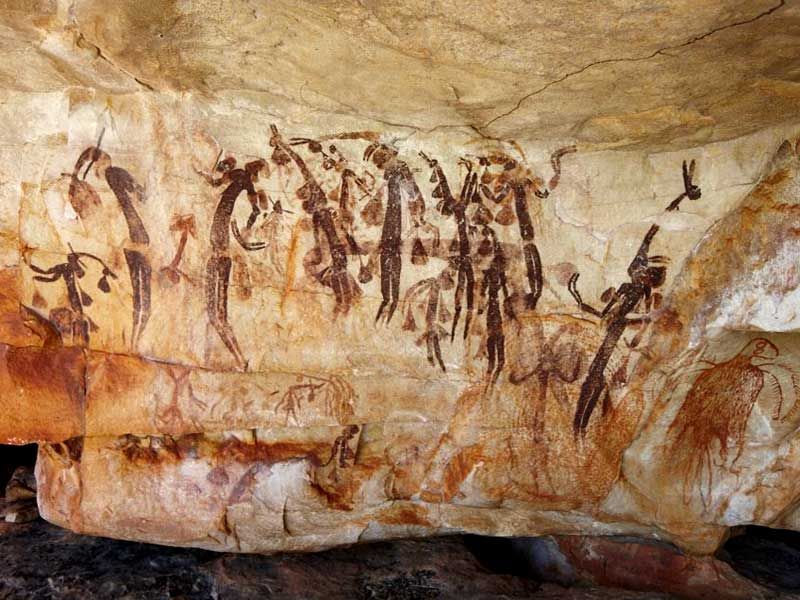

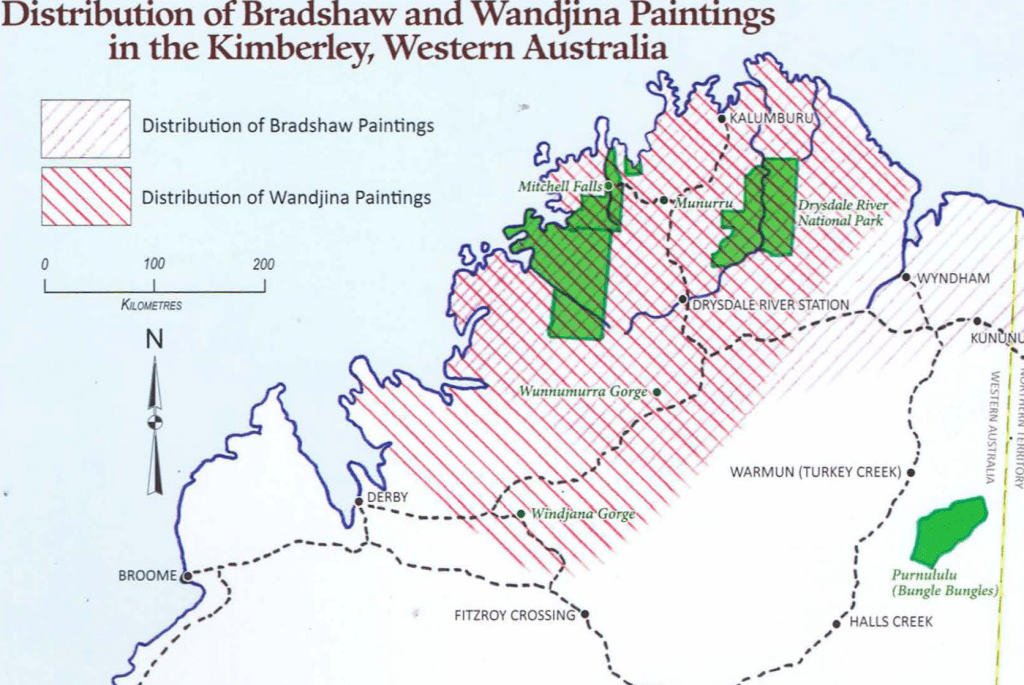

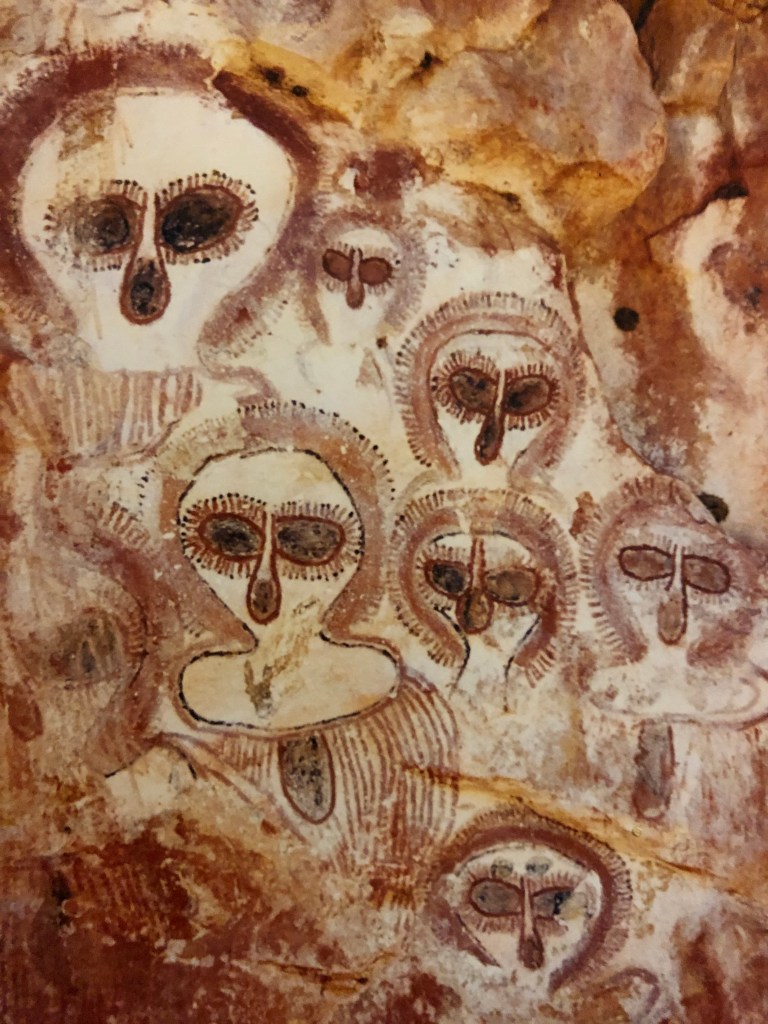

For 120 or so years these intriguing rock paintings — sophisticated, finely outlined then painted, and now lithified, actually grown into and become part of the rock — were known by the non-Aboriginals who discussed them as ‘Bradshaws’. Today it would be more acceptable to call them Gwion Gwion, their name in Ngarinyin. In their spread across the Kimberley, an area as big as Spain, they are also known among local Aboriginal groups as djimi, giro giro (kiera kiro or girri girri), and guyon (or kuyon).

Gwion Gwion can refer to the work of the artists who are believed to have painted them, children of Djilinya, a mythical female or, alternatively, the long-beaked bird Guyon (‘sandstone thrush’) that pecks at rock faces to catch insects which sometimes causes their wing or other body parts to bleed. (That’s the northern Kimberley story. In the central Kimberley they say the beak bleeds.) The blood trickles down the rock to create these images which are almost uniformly and unusually a very dark browny-red, ‘mulberry’ as it has been described. They are detailed, precise and have all sorts of ornament.

The chief Bradshaw fans have divided them into four types:

- Tassel figures: have tassels hanging from their arms and waists, along with various other recognisable accessories, such as arm bands, conical headdresses and boomerangs. This style is the earliest, most detailed and most common.

- Sash: while similar in appearance to the Tassel figures, the Sash body is more robust and has a three-pointed sash or bag attached to the figure’s belt.

- Elegant Action Figures: are almost always shown running, kneeling or hunting with multi-barbed spears and boomerangs. These are difficult to place in the style sequence as they are the only figures that are not superimposed over a painting from another period. In fact they are the only style that has not been defaced.

- Clothes Peg Figures: were named (by Walsh, see below) after their resemblance to old wooden clothes pegs. They are also referred to as Straight Part Figures. In a stationary pose, segments of their bodies are missing, such as their waists, arms and feet, the result of different colour pigments, such as whites and yellows, fading over time. Many of the images are shown in aggressive stances. At least one panel [below] shows a battle with opponents arrayed in ranks opposite each other.

These are clearly not Aboriginal categorisations. Nor are the more readily encountered detailed descriptions of the figures.

A fine Sash Bradshaw displaying a wide range of the accoutrements found associated with this Group. The long head dress has a single feather mounted through its upper extremity, with double tiered tassel extremity. A Prong Variation of the Winged Headdress feature is mounted to the right side of the head. A neck-mounted dillybag is visible beneath the right armpit, and a cluster of four Chilli Armpit Decorations beneath the left. … [Etc. Etc.] The Bradshaw Foundation

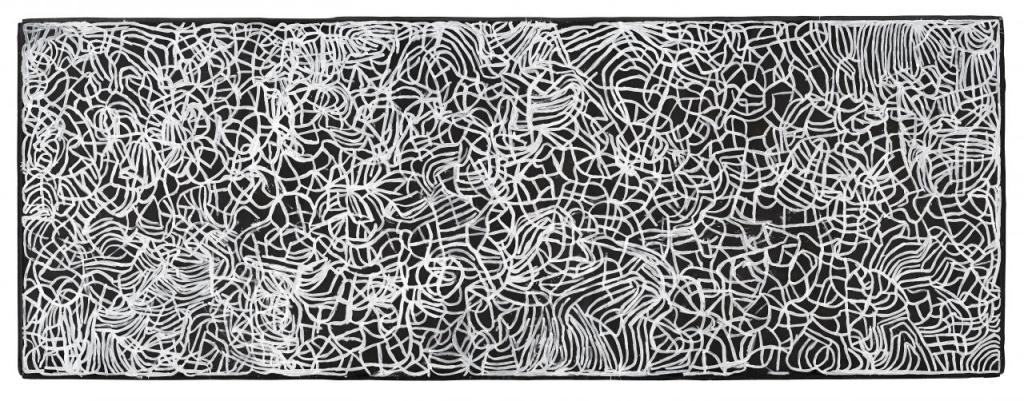

In the same area the very different Wandjina figures can be found.

These figures can be clearly placed. They belong to the Mowanjum peoples of the Kimberley and that attachment is active and strong. They are cloud and rain weather spirits. A number of the paintings have been convincingly dated in their original forms from about 3800-4000 years ago. It has been suggested that this art style was generated by the end of a millennium-long drought occurring across northern Australia and the beginning of regular annual (and life-giving) monsoons. Wandjina typically have no mouth. One explanation for that is that rain would never stop if they did.

These paintings are still believed to possess great power and therefore are to be treated with great care and respect. According to Mowanjum belief, annual repainting in December or January ensures the arrival of the monsoon rains.

The automatic response might be to think that Wandjina must be much older than Gwion Gwion. But as this photo illustrates it is not uncommon to find Wandjina superimposed over Gwion Gwion. Leaving a puzzle.

********

The Gwion Gwion have drawn, and transfixed, European ‘enthusiasts’ since land speculator Joseph Bradshaw stumbled over his first set near the Roe River in the Kimberley in 1891. He was looking for suitable pasture with his brother and seems to have been lost. He reported his finds in the subsequent year. His drawings, pooh pooh-ed initially, proved to be remarkably accurate and detailed. He also made his own comments including the much quoted:

‘The most remarkable fact in connection with these drawings is that wherever a profile face is shown, the features are of a most pronounced aquiline type, quite different from those of any natives we encountered. One might think himself looking at the painted walls of an Egyptian temple.’

In 1938 Doctor Andreas Lommel, a member of Germany’s renowned Frobenius Institute, lived for several months in the Kimberley researching Aboriginal rock art. After his second expedition to the Kimberley in 1955, he stated his belief that the rock art he referred to as the ‘Bradshaw Paintings’ may well predate the ancestors of present Aborigines.

And so we’re off and firing. As well as inviting the attention of unusual and highly imaginative whitefellas, Gwion Gwion really do seem to have some magical powers. You see them and you MUST construct your own story around them. And it WILL be the right one. OKAY?

Here’s one of ever so many.

‘As the Bradshaw Paintings progressed in time they displayed a distinct trend of decline into barbarism. The decline is noticeable in artistic skills, composition, themes, motives and aesthetics. There is a noticeable increase in imperfect figures, and short stocky human forms appear together with the slender Bradshaw figures. Both homo-forms are clad in the Bradshaw tradition. The finely choreographed graceful postures gradually transit into wielding of weapons.

‘The cause of multilateral decline is seen in the emergence of an external pressure, infiltration, inherent internal decay and eventual annexation by barbaric and warring new comers, probably the earliest wave of invasion (from the Indian sub-continent) by what is referred to as the Australian Aborigine. Such a quiet conquest infers the Bradshaw People were peaceful and hospitable, unaccustomed to deceit.’ (‘Unaccustomed to deceit!’ You can read that into 20,000 year-old rock art?)

This is ‘Anthropologist GL Seymour’ and the publication which quotes is called Australia for Everyone, guidance for visitors to Australia. I can find plenty of other material like this, but I can’t find any other reference to him on the net except for quite a number of word-for-word transcriptions of the passage above along with his summary. ‘The invaders eventually overtook the rule [sic] and overwrote the sophisticated culture, concluding that what the British did to the Aborigines, they themselves appear to have done to the Bradshaw People upon their arrival in Australia’.

********

Bradshaw’s name lives on in The Bradshaw Foundation, an international organisation dedicated to rock art founded by sculptor John Robinson who grew up in Australia but subsequently lived in England. He is one of those who have been much moved by a trip to the Kimberley for the purpose of looking at rock art. American billionaire Robert A. Hefner is its current President and Hungarian industrialist Damon de Laszlo is Chair of its Board.

This is part of what the Foundation’s website has to say about Gwion Gwion rock art today:

The Australian Rock Art Archive currently focuses on the rock art of the Kimberley region, featuring the Gwion Gwion rock art, also known as the Bradshaw paintings, and the Wandjina rock art. The Gwion Gwion rock art is claimed to be the earliest figurative art in the world. Sixty-five thousand years ago, our ancestors crossed by boat in groups from Timor into Australia. It is just possible that some members of these groups were assigned the task of recording their beliefs, hopes, fears, and spirits by painting on the rocks of carefully considered locations. If that is the case, the cave paintings of the Kimberley region of north west Australia could be among the earliest figurative paintings ever executed. …

The approximate date of the colonisation of this continent is based on scientific evidence. The date of the Gwion Gwion rock art is not. In fact, the mystery surrounding this distinctive style of rock art, who the artists were, when they were painted, and for what reason, is part of their attraction. Unfortunately this mystery has sometimes been used as a political vehicle to hijack the art, and in so doing, obscures their beauty and sophistication.

Speaking of which:

‘Commenting on the idea of a referendum to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in the constitution, Liberal Democrat senator David Leyonhjelm says there are doubts about whether Aboriginal people were the first occupants of Australia. “There are some anthropologists who argue that”, he said this morning. Senator Leyonhjelm cited the cave art known as the Bradshaws or Gwion Gwion in the Kimberley in Western Australia, although he mistakenly said they were in the Northern Territory. “There are some anthropologists around who say they are so distinct from more recent Aboriginal cave paintings, that they suggest that there was a previous culture … to the Aborigines,” he said. “The fact that there is even a doubt raised about it would suggest to me that it is not necessarily a good thing to put in the constitution.“‘ (ABC News: 25/6/18)

********

I’ve seen three sets of Gwion Gwion. This is my rather ordinary photo of one.

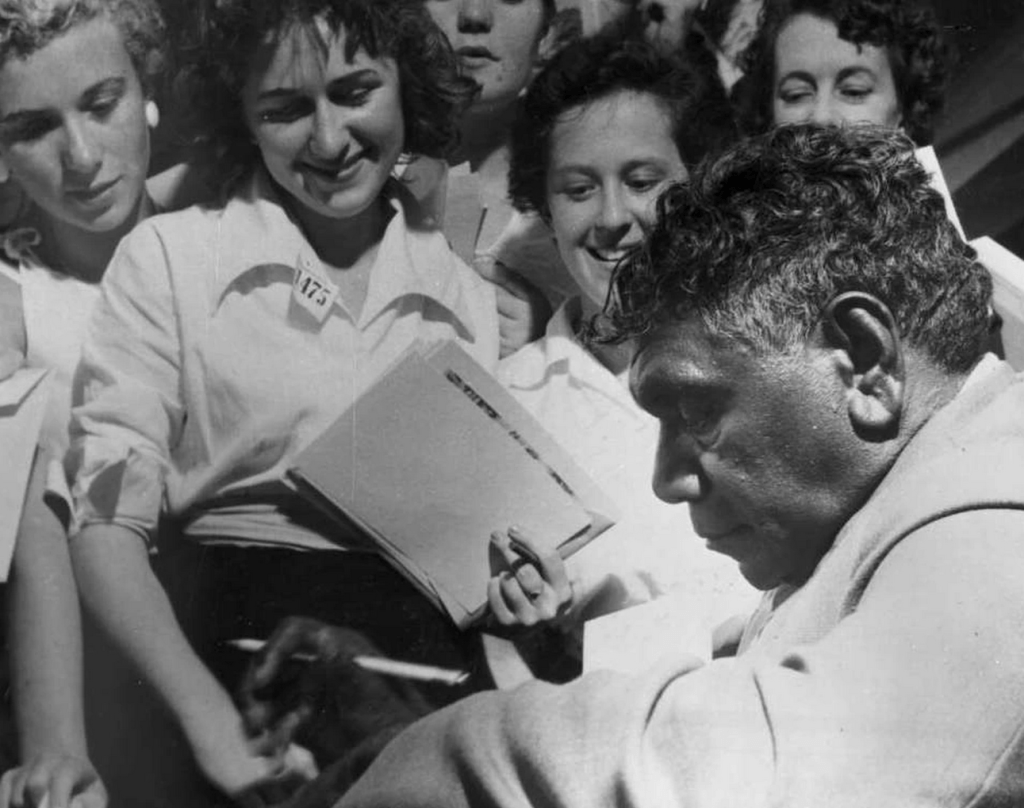

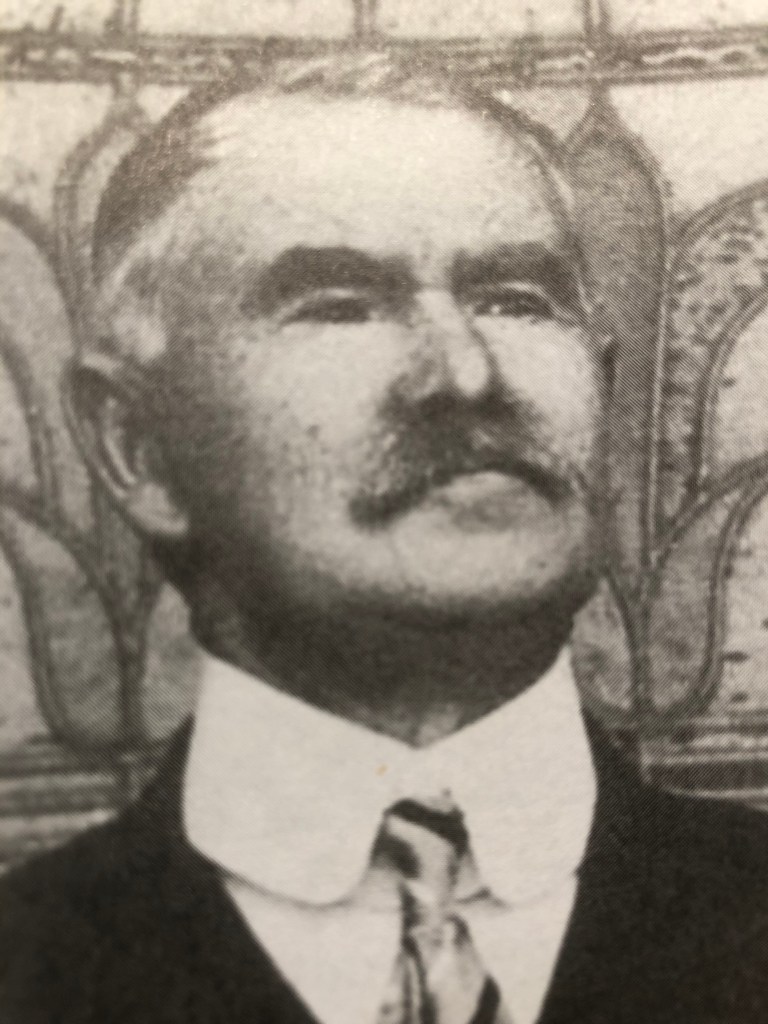

Grahame Walsh (at right) saw thousands. (8742 have been recorded to date.) Before his death in 2007 he had created a set of 1.2 million slides of rock art now in the custody of the Kimberley Foundation.

He is the author of what is believed to be one of the truly magisterial works of its type, ‘Australia’s Greatest Rock Art’, constructed at the Government’s behest as part of the Bicentennial celebrations. One hundred individual sections cover the rock art of every Australian state and territory as well as every major rock art region and style: materials, craft details, location, antecedents, context. 390 colour plates. Weight: 3 kgs. Awarded the Thompson Medal in 1990 by the Royal Geographical Society. Today you can buy a new copy for $1200, second hand for $800 to $380 (pretty scruffy).

In 2004 he told Michael Winkler for ‘The Age’: ‘[Australian rock art] is my life’s obsession, and I’ve devoted everything I had to it. Health, wealth, personal happiness and friendship, I’ve sacrificed the lot in the quest. Now I’m 60, two buggered knees, my wife’s gone, and I’ve got no dough — but I’ve gained a higher understanding of the cognitive development of humankind than probably anyone else in this country.’ And all that after failing Year 10, leaving school at 16, becoming a newspaper photographer and then a park ranger in Queensland’s Carnarvon National Park.

He believed that the Bradshaws provide irrefutable evidence of another people (the ‘Erudite Epoch’) preceding the Aboriginal peoples of the Kimberley.

Besides being utterly consumed by his mission, it seems like he was a nice guy, well meaning, open, even innocent. In the video below the widely respected Dame Elisabeth Murdoch, Rupert’s mother, proclaims Walshe’s insight and integrity. You can judge for yourself. The video also provides a very good look at the country and situations where Gwion Gwion occur.

********

Why does any of this matter? Are these just academic questions?

Well no … they aren’t. If Walsh was right, for example — and his views still have plenty of adherents — Aboriginal people have lived in the Kimberley for 10,000 years or less. But more to the point, they displaced the original ‘owners’. What does that mean for land rights cases for example? While whitefellas only have to have something for five minutes to establish ownership, the way the law is set up means that Aboriginal people have to establish occupancy virtually in perpetuity for their rights and title to land to be formally recognised (remembering this law supplants the operative idea of terra nullius, ‘nobody’s land’).

But even more importantly it cuts right into the notion, so important to Aboriginal culture and life, of permanent and enduring connection to the land, something that no one else has a right to. Always was, as well as always will be. Always.

********

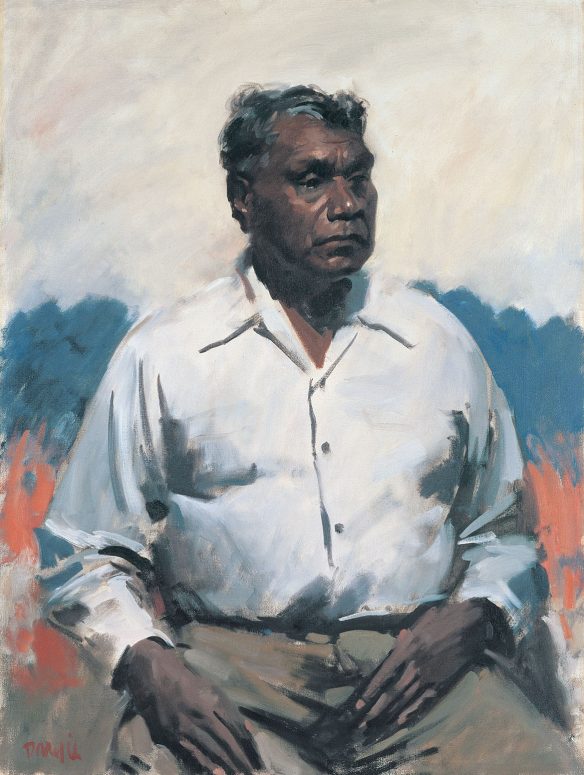

The photo which accompanied Michael’s story was taken in Alan and Maria Myers’ house in North Carlton. The dingo rather takes pride of place but look at the two other artworks.

Maria Myers played a fundamental role in the setting up of the Kimberley Foundation (‘Researching, preserving and promoting Kimberley rock art’). In a 2013 story on the WA 7.30 Report she says: ‘I’d like to get the piece of Australia’s story that’s locked up in Kimberley rock art and I think it’s also a big part of the story of the emergence of modern humans in the world’.

The Kimberley Foundation currently boasts Laurie Brereton as Chair of its Trustees, Maria Myers is now Deputy, and ‘Twiggy’ and Nicola Forrest are its chief patrons: heavy hitters, big money, considerable power. As well as its own quite sophisticated operations, the Foundation funds a Chair in Rock Art at the UWA and a Chair in Archeological Science at Melbourne Uni (where Alan Myers is Chancellor). In 2002 the Foundation was an enthusiastic supporter of Grahame Walsh and the most important source of his funds.

But in 2017 the Foundation decided Walsh was wrong.

‘The late Grahame Walsh’s meticulous recording of the Kimberley’s most remote art-decorated caves went on to become the bedrock of current research that appears to disprove his own theory of discontinuity. Kimberley Foundation Australia Chair Maria Myers, who knew Walsh well until his death in 2007, says a decade of scientific study of rock art based on Walsh’s legacy is revealing a different picture of prehistoric artistry in the Kimberley.

‘Walsh believed that no continuous link existed between the painting of the Gwion or Bradshaw period … and the beginning of the Wandjina period of wide-eyed spirit figures. They appeared to be made by different peoples, he concluded. But in the ten years since Walsh died, “We have found more and more sites that we don’t know whether to put in the clothes peg period or the early Wandjina period,” says Myers. “They are what Grahame always said he couldn’t find — they are transitional. So there is no period of discontinuity between the two.”’ (‘Rock Art Researcher Got it Wrong’ The Australian 25/9/17.)

Another amateur, Dr David Welch, a medical doctor based in Darwin, played a crucial part in the development of the new schema. His monograph ‘From Bradshaw to Wandjina: Aboriginal Paintings of the Kimberley Region, WA’ (2016) tells the story, this time as a result of working with dozens of Aboriginal groups and getting their stories.

The broadly agreed chronological sequence at present is

- firstly rock markings: incisions, grooves, hollows which might relate to ceremonial life, identity markers, changes in the landscape

- naturalistic: large sometimes life size animals, fish and plants. Hand prints or stencils

- Gwion: see above, except

- static polychrome figures (formerly described as ‘clothes peg’ figures): schematized, usually straight human forms; dominated by groups of people rather than deities, depicting headdresses, multi-barbed spears and spear throwers. They are finely painted in red and orange, with faded white and yellow paints, creating the illusion of unpainted or ‘missing’ parts

- painted hand: enormously varied with bichrome and polychrome depictions of objects, humans, animals, plants, lines, finger dots and non-figurative motifs. This diversity may show the marking of clan estates during the Holocene Period

- Wandjina figures: see also above.

And just how old are any of these? The Wandjina figures can be carbon-dated to 3,800-4,000 years before the present (BP). The ‘painted hands’ seem to belong to 7,000-10,000 years BP. Information about the age of Gwion Gwion art has been drawn from the brilliant and widely noted dating of a series of fossilised mud wasp nests built over paintings. (‘When the mud wasp collects sand off the floor she’s also picking up tiny pieces of charcoal.’) The oldest of these to date has been 18,000±1,500 years BP.

The naturalistic period presents some intriguing cases.

This is believed by some scientists to be a painting of a marsupial lion found under some small Gwion Gwion paintings. As far as we know marsupial lions became extinct more than 45-50,000 years BP, although Kim Akerman, the primary author of this article, thinks 25-30,000 years might be more likely.

It is generally agreed that the earliest rock markings were made at least 40,000 years BP.

And who was making this art? Very hot off the press from a group of South Australian researchers in partnership with Aboriginal families and communities:

[Via access to historical collections of hair samples,] we were able to map the maternal genetic lineages onto the birthplace of the oldest recorded maternal ancestor (sometimes two to three generations back) and found there were striking patterns of Australia’s genetic past.

There were many very deep genetic branches, stretching back 45,000 to 50,000 years. We compared these dates to records of the earliest archaeological sites around Australia. We found that the people appear to have arrived in Australia almost exactly 50,000 years ago.

Those first Australians entered a landmass we collectively call “Sahul”, with New Guinea connected to Australia. The Gulf of Carpentaria was a massive fresh water lake at the time and most likely a very attractive place for the founding population.

The genetic lineages show that the first Aboriginal populations swept around the coasts of Australia in two parallel waves. One went clockwise and the other counter-clockwise, before meeting somewhere in South Australia.

The occupation of the coasts was rapid, perhaps taking no longer than 2,000 to 3,000 years. But after that, the genetic patterns suggest that populations quickly settled down into specific territory or country, and have moved very little since.

The genetic lineages within each region are clearly very divergent. They tell us that people – once settled in a particular landscape – stayed connected within their realms for up to 50,000 years despite huge environmental and climate changes.

We should remember that this is about ten times as long as all of the European history we’re commonly taught.

This pattern is very unusual elsewhere in the world, and underlines why there might be such remarkable Aboriginal cultural and spiritual connection to land and country.

As Kaurna Elder, Lewis O’Brien, one of the original hair donors and part of the advisory group for the study, put it:

Aboriginal people have always known that we have been on our land since the start of our time, but it is important to have science show that to the rest of the world.

What a story.

********

And now for something completely different … READ ON.