Boston is the seat of the American Revolution, not where everything happened, but the absolute heart of the ferment.

Like a lot of these blogs, this is a story about colonialism. In this case an uprising of colonials against their overlords. One thing that cuts it out from the herd is that this time the colonials were white Europeans and the whole show takes on, so to speak, a different complexion.

The American Revolution: is it too much to say a marker in the history of the world? A beacon of liberty and idealism? Realised? Hold those in your head.

A further question, although it might damage the seriousness with which the previous questions are considered. Does walking round historical sites per se do anything for you? It behoved us to find out. We’re in Boston walking the Freedom Trail to find the American Revolution.

• • • • • • • • •

On a cold and wet day we got out of the subway at Park Street arriving at the start point, The Boston Common, America’s oldest public park.

It has a story of its own. The first attempt at European settlement on the Shawmut Peninsula (now, in a much expanded version, downtown Boston) failed. But one man, William Blackstone (or Blaxton), decided to remain and lived alone for five years on his allotment of 50 acres at the foot of Beacon Hill.

Meanwhile a group of Puritans had settled in Charlestown on the north side of the Charles River but were struggling with rocky soil and a lack of fresh water. Blaxton sent them a letter of invitation (how would he have done that? Not by post certainly) inviting them to move south and share its benefits. Over time that population enlarged and Blackstone was encouraged to sell most of his very large plot for common use: 44 acres for £30, each household contributing six shillings. He went elsewhere.

130 years on in 1768, a force of 4,000 British troops was sent to Boston to quell ‘disturbance’ and to re-establish ‘public order’. They were quartered on the Common. Unsurprisingly, their arrival had precisely the opposite effect. Unsurprisingly, there was a high rate of desertion.

We saw The Common in several lights. This was the first time. It looked and sounded a lot like a drug deal. Other times in better weather it was pulsing with crowds doing all the things that crowds do.

On the Tremont Street side one encounters this. It’s called ‘The Embrace’, and commemorates an embrace between Martin Luther King and his wife Coretta after King had given a speech on this spot about human rights and those of African Americans in particular. It’s enormous (note the people for scale) and brilliantly constructed but it’s hard to find much fondness in it. It looks just a tiny bit like Dali’s ‘Soft Construction with Boiled Beans’. I just discover that it’s new. It had only been there a few months when we saw it.

The Park Street Church towers over the eastern corner of the Common.

It wasn’t even there during the Revolution. ‘America, My Country ‘Tis of Thee’ was first sung here but I don’t think that counts.

Next door is the Granary Burying Ground.

Benjamin Franklin’s parents are buried under the dominant obelisk, the biggest memorial in the cemetery. (His parents!) John Hancock has a big memorial invisible over on the right. Paul Revere, Peter Faneuil, James Otis, Crispus Attucks, and Samuel Adams are also buried here although their graves are not obvious. The guy in the red top coat would have known but he was busy declaiming.

This is the site, and site only, of America’s first public school, the Boston Latin. Hiding in the bottom left hand corner is a statue of Benjamin Franklin who was a student there until he dropped out. It is claimed that there was a shout of ‘Close your books. School’s done and war’s begun’ on April 19 1775. Treat that as you wish.

In the background between the two sets of statuary is America’s oldest commercial building with a sign on it saying ‘CHIPOTLE Mexican Grill’. Among other things, it was once a publishing house which produced The Scarlet Letter, Walden and Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Good, interesting, but not really about liberty. The statues are about posh Bostonians ignoring the plight of the poor Irish immigrants who eventually took over Boston and had one of their own elected as President of the whole country.

The Old South Meeting House, closing in a bit here. This is where 5,000 Bostonians gathered in 1773 to hear whether there was any new compromise in the British policies enraging them. There wasn’t. The Sons of Liberty marched from here to the docks (not far, five or ten minutes brisk walk) and 342 chests of tea were dumped into the harbour.

Even closer. The Old State House where so much of the talking action happened, the forum for the orators and lawyers of the colonies. The British officials were consistently outplayed for a decade before the seams came apart.

Under the balcony is a memorial to the place, actually nearby rather than exactly here, where in 1770 the ‘Boston Massacre’ occurred, the place where seven or five locals were shot and killed by British soldiers.

In time the Declaration of Independence was read from its balcony.

Paul Revere’s House. ‘The ground floor includes a typical late-18th century kitchen with cooking implements and a large Hall restored and furnished to look as it might have when the first owner lived here. Upstairs chambers contain period furnishings from Paul Revere’s era, including several pieces that belonged to the Revere family.’ 10 bucks a head. We thought we’d let it go. But liked the car.

‘”One if by land and two if by sea”, Old North Church lit the way for the American Revolution.‘

The plaque says: ‘The signal lanterns of Paul Revere displayed in the steeple of this church April 18 1775 warned the country of the march of the British troops to Lexington and Concord.’

That’s it all right. Quite plain without the imminence of war, but that’s it.

Faneuil Hall. We are closing in now. Peter Faneuil was a successful businessman, one of the few who sided with the angry people early. The hall was an important meeting place for the sharing of emotions and ideas and organising events.

But who is that there in front on the podium?

‘Samuel Adams 1722-1803. A Patriot. He organised the Revolution and signed the Declaration of Independence.’ And you’ve never heard of him. Or have you? Was it just me?

• • • • • • • •

The American Revolution: is it too much to say, a marker in the history of the world? No. Unquestionably it was. Even Zhou Enlai would agree sufficient time has passed to agree it had enormous impact. But how should we characterise it? What does it look like without the glories of its post facto descriptions and justifications? Was it an unusual perhaps unique high point in the history of idealism? Or does it look different at home in its underwear?

• • • • • • • •

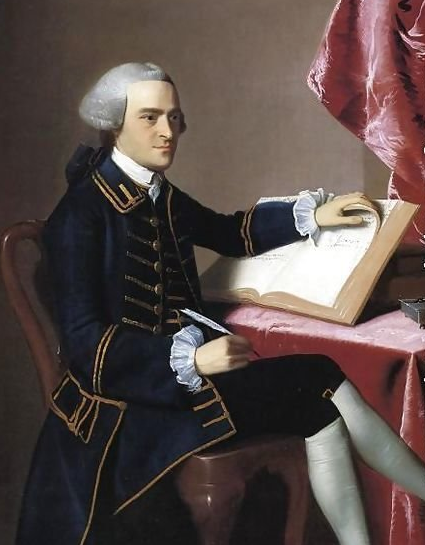

The Revolution came alive for me in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts in a way that it didn’t on the walk. That can happen. But in the gallery — and of course another great American gallery, a big call but better curated I think than MOMA — there they all were. John Singleton Copley had painted them all.

I had been reading Stacey Schiff’s book The Revolutionary: Samuel Adams. It had just been published and very positively reviewed but I was finding it hard going. Over-written I thought, and she seemed to be making a point of his ordinariness, highly principled, very rational, but ordinary. Something like the kiss of death to a biography. Nonetheless it got me in for reasons which I will explain.

As far as I understand it, and it isn’t very far, this is what happened.

Between 1700 and 1775 the European population of the 13 American colonies multiplied more than 12 times. As a consequence they went from being isolated outposts to something quite different. Urban clusters were beginning to take form, small enough to have strong community contacts and interaction, but big enough to develop a degree of sophistication: with growing professional classes, a caste of prosperous native by birth merchants emerging, and the surfacing of a group of people with enough freedom from the grind of manual work to think and put their thoughts into writing. Public discourse was emerging with loyalty to its locale rather than locations 3000 miles away.

In the mid 18th century the American colonies might be considered teenaged societies, full of hormones and vitality but at the same time roiling away with unfocused resentments, unenthusiastic about adult direction. And the adults weren’t much help. Britain, considerably weakened by the Seven Years Wars with France and India which lengthened into nine years, was not taking much notice of the emerging maturity of these colonies.

Francis Bernard was sent to govern Massachusetts in 1760 seeking a quasi-retirement posting to allow him to indulge his interests in classical music and good books. These plans were consistently disrupted by vexations in the local parliament and commotion in the streets. He consequently made judgments that he and his employer would come to regret. It was he who ordered the regiments of troops for Boston. Thomas Hutchinson, a native of Boston who succeeded him, appears to have been worse. Pompous, clever, arrogant and possibly malicious, his life seems to have been dogged by a continuing rumble of disappointment and failed expectation. ‘Everything in American life happens contrary to probability’, he wrote. You can’t help think that if both men had been better attuned to their environment and more inclined to negotiation the revolution may have at least been postponed.

In England the erratic George III reigned and news from America was both unsystematic and deeply coloured by its sources. Benjamin Franklin was in a position in the mid 1770s to discover in London eight months worth of formal correspondence from the colonies most of which had not been opened.

Samuel Adams was one of the primary exponents of public discourse and one of the authors of those unopened letters. Although his family was quite wealthy (church deacons but also brewers you mightn’t be surprised to hear), he appears never to have had much money and to have stumbled badly in his role as a tax collector leaving him twice with the responsibility for paying other people’s taxes. But with pen in hand or standing, speaking notes in hand, he was indefatigable.

He was educated at Harvard, already more than a 100 years old, and became absorbed with the demands of logic and rationality. His writing had great verve but also great clarity. And great volume. Boston had three of the four first newspapers published in America, usually weekly, not very thick but given sometimes to acid commentary and bitter personal attacks thus guaranteeing an audience. In the 1760s the Boston Gazette had a circulation of 2000, very substantial in the circumstances. Adams began writing for The Independent Advertiser but then moved to the Gazette where he was a regular correspondent although, as was the custom of the times, writing pseudonymously. These newspapers were the mass media of their day and played a huge role in shaping public opinion.

Adams was also a politician, a long term member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, holding senior roles and building and maintaining influence. He had a range of allies including his frontman for a time James Otis, a lawyer and renowned orator but with shakey mental health which eventually left him disabled. His cousin John who became the second President of the United States was a close collaborator. John Hancock, son of wealthy merchants, provided the money which helped to keep Adams out of debtor’s prison. Adams became his mentor and friend for a decade or more until they fell out over Hancock’s ‘extravagances’. Adams thought them inappropriate to his role. (It is Hancock’s florid signature at the top of the Declaration of Independence which has led to ‘John Hancock’ being used in America as slang for ‘signature’. He was at that time President of the Continental Congress, the vehicle for the co-operation of the colonies.)

But Adams could legitimately be thought of as the coordinating force of this phase of anti-British sentiment. He was the one writing the critique. Jefferson may have written, ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness’, but Adams would have had to hand the list of 27 grievances which follow. They are the substance of what he had been corresponding with the Crown and its representatives about for more than 20 years.

John Adams, John Hancock (with gold braid), Thomas Hutchinson, James Otis all by Copley.

There is a broadly agreed set of milestones in the progress of the American colonies towards declaring independence. They mostly seem to to relate to tax, commonly an unedifying and complex topic.

As mentioned above, Britain was in a weakened financial state after its commitment to a long and draining set of wars and there was a dominant school of thought in the British Parliament that the colonies, if not providing income, should at least pay their own way.

This is what the British Parliament’s Sugar Act of 1764 was intended to achieve, the first taxing of the American colonials. It was not well received. The Boston Town meeting, a semi-formal body, approved instructions developed by Adams with help from Otis that the tax legislated under this Act was not to be paid. Then in response in 1765 the British Parliament with its nose increasingly out of joint, passed the Stamp Act which required colonists to pay tax on printed materials.

This doesn’t sound like much but it sparked a furore which encouraged Adams to organise a boycott of British imports. Andrew Oliver who was charged with the implementation of the Stamp Tax, was hanged in effigy from a tree, the ‘Liberty Tree’, in the Common. The sign read, ‘What Greater Joy did ever New England see / Than a Stampman hanging on a Tree!’ Sides were drawing up. The Tree was later cut down and used for firewood by British Loyalists during the siege of Boston.

Oliver’s house was ransacked shortly after. On the same night a mob surrounded Lieutenant-Governor Hutchinson’s house to demand his agreement to rescind the tax. (Oliver was his brother-in-law. Hutchinson’s family held 11 significant paid posts in the Massachusetts public service at the time. He himself had four of them.) They came back some nights later and completely gutted Hutchinson’s North End mansion, even dismantling and taking its cupola. This is one of the events that led the British to send a detachment of troops to Boston.

In 1770 the Boston ‘Massacre’ occurred. (This is an engraving ‘Engrav’d, Printed & sold by Paul Revere’ who seems to have been highly entrepreneurial as well as a very capable odd jobs man.)

A mob of three or four hundred Bostonians was baiting British soldiers near the Old State House, spitting at them as well as throwing various projectiles, taunting them to ‘Open Fire’ in return. One sentry, Private White, was knocked down with a stone and then did open fire as a group led by a Black/ Native American former slave then whaler, Crispus Attucks, charged towards them to attack with various ad hoc weapons. Attucks has a role in history as ‘the first person killed in the War of Independence’.

This story is very murky. Other soldiers opened fire, the command may or may not have been given, and three (or five) people were killed immediately, two (or three) dying later of their wounds.

This of course was a disaster for the British. What? Killing their own (WHITE) subjects now?

With emotions running very high, Samuel Adams asked his cousin John to lead the legal defence of the soldiers so that justice could be seen to be done, ineluctably. Later, when the charges were dismissed by that same process, he wrote a furious critique of what had happened, not really shifting his position but, as so often, being absolutely fixed in his view of what the right thing might be. In this case, hanging of the soldiers. He moulded this event, as he had many others, into his spacious narrative of English infamies.

The reach of his writing expanded through his creation of a ‘committee of correspondence’ initially throughout Massachusetts but spreading in reasonably short order to the other 12 colonies some of which were ripe for this sort of talk. (But not all. Maryland, for example, was not a signatory to the Declaration of Independence.) The British tried to outlaw and short circuit this process which was conducted quite secretively, but failed. Very hard to stop something like that. Strategically it was essential for the colonial agitators; obvious, but still a masterstroke that no one else had tried.

And then in 1773 came the Tea Party.

An additional cause of the British Government being short of money was that the taxes which the East India Company had paid (more than £400,000 per year, huge sums) were evaporating because of Dutch smugglers undercutting its prices. Another consequence was the creation of a massive stockpile of tea. Lord North, who had his hand on the wheel in England, had an obsessional interest, not in the rights or otherwise of the home country to tax the citizens in its colonies, but in getting cash to pay the British employees who worked in them. Why should the colonies cost Britain money!? he thundered in his Parliamentary exclamations.

So the Townshend Revenue Acts were passed placing a tax on the import of all British goods including tea to the US colonies, while at the same time taking determined steps to increase the importation and sale of the East India tea mountain. In fact these Acts officially made tea cheaper than it had been. The tax was reduced from 25% to 10%, making it one penny per pound cheaper than it was when purchased from sources supplied by Dutch and other smugglers. But the Americans weren’t much interested in such fine points. It was the gesture – which could be very easily read – rather than the detail.

In October 1773 seven ships full of tea were sent to the colonies, four bound for Boston, and one each for New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston. News of the new tax and its consequences only reached America shortly before the ships.

In New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston, protesters compelled the tea consignees to repudiate their interest. In Boston Hutchinson forcefully urged the consignees (two of whom were his sons) to stay the course.

On the ships’ arrival in Boston Adams convened a meeting at the Old South Meeting House attended by an enormous crowd, nearly half of the city’s population. It was during this meeting — Adams struggling and failing to maintain order — that the Sons of Liberty marched off to meet their mates who were in charge of the discharge. This group was almost certainly dockers. It was noted how capably they handled the cranes and the ship’s unloading machinery. A few of them wore fancy dress which some took to be Indian.

Several thousand onlookers were in attendance and strangely when investigations occurred no one could identify any of the people involved. No one. And you don’t think about this, but apparently there was so much tea (about 46 tonnes) it formed into viscous mats on the surface of the water and didn’t disperse for quite some time.

The British, for many reasons not least the threat to their authority, are mightily affronted. They have some time to think about what they are going to do, what recompense they are going to extract and who will pay. Little of immediate consequence occurred, but the issues are stacking up into quite a pile.

It is two years later when things have escalated considerably that news comes to hand that colonial militias are stockpiling weapons, both private and supplied by the French, at Concord and elsewhere upstate. The redcoat regiments begin to gather… what were they going to do? Were they going to march inland or were they going to be shipped up the coast?

At left, the young Paul Revere, Copley again in the Boston gallery.

Paul Revere’s Ride might be better known than Samuel Adams. This is the thing about messaging. You write a very popular poem 90 years after the event (Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem was published in the Jan 1860 edition of The Atlantic), and you can say what you like.

“One [lantern] if by land and two if by sea”. Yes that was the signal but it wasn’t for Revere; it came from Revere. He didn’t row himself across the Charles; he was taken by a crew organised by the Sons of Liberty. He didn’t get to Concord that night. (It’s quite a step. It took us nearly 50 minutes on a turnpike in a very comfortable car.) And it’s only Revere. No it wasn’t. Warrants had been issued for the arrest of Samuel Adams and Hancock who were in Lexington, and William Dawes rode with Revere to warn them. They were joined by a local doctor, Samuel Prescott, at Lexington for the ride on to Concord. All three were detained by a British detachment. Prescott and Dawes escaped. Revere was taken back at gunpoint to Lexington. Only Prescott got to Concord to warn the militia. Prescott.

The next day, April 19, 1775, with battles at Concord and Lexington, the War of Independence began.

• • • • • • • •

Samuel Adams has been a controversial figure. Hutchinson, in particular, wrote bitter diatribes about him accusing him of being a rabble rouser and of leading, in person, riotous behaviour. Others, historians, have labelled him a dishonest character assassin or even ‘Machiavelli with a cloven Foot’. It was more common in the 19th century to think of him as an old-fashioned and not particularly effectual Puritan. In the 20th century we have psychological studies (Harlow, 1923) describing him as a ‘neurotic crank’ driven by an ‘inferiority complex’, and a broader view that he was not much more than a propagandist with a dictatorial manner.

But I think I know what he was like. He was a Methodist: not literally, but like Methodists can be, fiercely principled (and very much against mob violence), urgently driven by ideas about what a society and its citizens should be like, the rights they should have and which should govern the shape and tenor of their community. Driven to the point of obsessiveness about this. Consumed. Very little interest in private fortune or ‘success’ as it might commonly be described. In fact disturbed by displays of ostentation. (See his rejection of Hancock for example.) Disciplined, and partly because of that discipline, able. Energetic because driven and because he doesn’t drink much and his socialising is usually in the service of his cause. And for these reasons, a bit annoying. But if you want something done, hire a Methodist (except that they’re not for hire).

I also know what he was up to with his writing. On a comparatively tiny scale I have done it. I have watched and participated in the construction of a cause through let’s call it pamphleteering although it is much much more. You construct a set of simple ideas and embed them in a deep and familiar understanding of your audience’s context. You repeat them in various ways, you embroider them, you find local examples to which the audience can relate. You find ways of making the cause both intimate and shared. This is what we’re all ‘thinking’, ‘thinking’ in inverted commas because it’s really what we’re all feeling. You give uncertainties a focus and a cause. You find and name an enemy and ways of diminishing them. All in a good cause.

I’ve suggested that the colonies at the time were ‘teenaged’ societies. In 1765 the population of Boston was 15,520, a country town; the colony of Massachusetts as a whole had 245,718 European inhabitants; the 13 colonies as a whole less than 2 million. I’ve also said they were likely to be ‘full of hormones and vitality’ and ‘roiling away with unfocused resentments’. In 1765 and on, there was so much opportunity to focus those resentments, and even though Adams might have had the cleanest of hands there would always be others who enjoyed the edges, the jokes and caricatures, the slander, the accusatory gossip, and yes the rabble rousing, and yes even the tar and feathering that happened to the consignees of the tea in Philadelphia and Charleston. Relishing all that really. Serious entertainment.

As one might imagine, a great deal of investigation has gone on into when the idea of becoming independent from Britain emerged. Schiff is consistently interested in this question and decides that it really wasn’t until 1770 or later that Adams was entertaining the idea of seeking independence. The focus of his work for two decades had been trying to get the boss to mend his ways, not to resign. He’s a Methodist, a committeeman, not a natural revolutionary. He is long-sighted enough to be very worried about the consequences of declaring independence. He may well have been wondering how many of his countrymen would die in a war with Britain.

Adams’ message which spread far and wide was ‘no taxation without representation’, a good one. Clear and unarguable really. Talk about ‘freedom’ and ‘liberty’ was around, but I would say as atmosphere, easy noise. It didn’t seem to have much concrete purchase. Even in late 1775 Jefferson was saying in a letter to his dear friend (at the time) and confidante John Randolph: ‘I am sincerely one of those, and would rather be in dependence on Great Britain, properly limited, than on any other nation on earth, or than on no nation.’ It is also easy to forget the large percentage of Americans who stayed committed to the British Empire and fought in the war as Loyalists, and the immense complications and confusion which arose after Independence had been declared.

I am prepared to suggest that there wasn’t a vision splendid of an egalitarian society in circulation, except perhaps over port late at night among intimates. While talking about equality, the Black slaves, for example, were left out of the considerations of the Declaration of Independence in order to manage the sensitivities of Southern colleagues. (The British had the nerve to use this as a critique.)

It wasn’t ‘Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness’ that motivated the colonists, it was that they didn’t want to pay more, or perhaps any, tax and, more to the point, the British and their representatives were at the same time both ignoring them and giving them the shits. Adams knew that. He knew his audience in a way that the British and those representatives never seemed to, and he unquestionably massaged his accounts of events in that direction; not lies, but you could at times be forgiven for thinking it just might be shading into propaganda.

Of course, once the fighting started all this counted for nothing. Forget reasons and argument, forget purpose and long views. You’ve just got to pick a side and try to be the winner. THEN you can start talking about ‘certain unalienable Rights’. You pop a writer in a room for four days and he can come up with stuff like that. And that’s what happened.

Adams melts away after the war begins. He’s in his late 50s, an oldish man in the 1770s, although there is a portrait of Paul Revere (that man again!) looking very hale in his late 70s. A bit liverish with his political companions, Adams has got ‘tremor disease’ in his hands which in a few years won’t allow him to hold a pen. He has a term as Governor of Massachusetts, but the national running — the ongoing Big Picture — is made by people who have flair and a certain type of presence he hasn’t, people whose names you remember: Jefferson, Madison, Franklin, Washington.

• • • • • • • •

Look. Don’t think about this too long, but could there be a mass of people in the US at present with unfocused resentments? Could they be angry about something both simple and fundamental like not having enough money when they can see others awash in it? Could they need an enemy to blame? Could there be groups willing to construct a worldview for them which identifies and describes that enemy? Is there a simple message or two that they can chant. Say: Build the wall, or … Make America Great Again (capitalising each word for emphasis). Is the difference between 1770 and today simply that today there is no Samuel Adams apparent? Or has their Samuel Adams become our Fox News? If so, what happens then? It might be more like 1770 than you think.

But don’t think about this too long. Come driving instead.

Pingback: THE 10 BEST PAINTINGS IN THE WORLD: New York | mcraeblog

Wow- a very powerful and thought-provoking piece. I very much enjoyed it David, and think your concluding remarks have some validity – unfortunately.

David, I hope you didn’t miss the bass relief sculpture in front of the State House but on the other side of the road. It depicts the battalions of African Americans who volunteered to fight for the North in the Civil War (although they were led by White Americans). This sculpture inspired the great American poet, Robert Lowell, to write what I consider his best poem, For the Union Dead. I urge everyone to read this poem and have a look at the sculpture (there are photographs of it on-line). The first time I went there in 1975, there was no-one at the sculpture; the second time I went there in 2008, there were many people around it and one fellow was dressed up in Revolutionary clothes, declaiming the poem for all to hear. He would recite the whole poem, wait for a while until the crowd changed, and then recite it again.

I’m trying to load my photo of it Andrew but it won’t go. We’ll just have to assume it’s there. And we didn’t miss it.