Yeah, well he couldn’t work it out either. We asked him.

Yeah, well he couldn’t work it out either. We asked him.

Tram (just visible in the background, the orange and yellow one) from Dogo Onsen to Okaido. Take the 10.02 JR bus bound for 落出. Get off at 久万中学校前 where it might be late. The driver of the connecting Iyotetsu bus bound for 面河 usually waits for 10 minutes. He will take you to 岩屋寺 where you get off and begin your walk.

And even though there was an unbroken procession of buses going through the Okaido stop, an hour and a half later that’s how it was. The traffic began thick but gradually dissipated as we headed down a very long, very narrow major street towards increasingly dramatic mountains. (Myrna’s photo: on her phone out the bus window) My Japanese expert, thank you Shelley, translated the sign for me. ‘CAUTION. From here on there are many curves.’ And so indeed there were. A long haul up and over a pass, but by the time we got to the bus change the mist had dissolved into a beautiful day.

My Japanese expert, thank you Shelley, translated the sign for me. ‘CAUTION. From here on there are many curves.’ And so indeed there were. A long haul up and over a pass, but by the time we got to the bus change the mist had dissolved into a beautiful day.

The first temple was about 800 metres from the bus stop and about 400 metres vertically, a heart starter. Iwaya-ji, The Cavern-housed Temple, Number 45, is set into the side of what is really a cliff face and was an intriguing affair. Internet information:

The first temple was about 800 metres from the bus stop and about 400 metres vertically, a heart starter. Iwaya-ji, The Cavern-housed Temple, Number 45, is set into the side of what is really a cliff face and was an intriguing affair. Internet information:

This temple is one of the nansho of Ehime Prefecture and is one of the sites where mountain recluses and wandering holy men once performed their religious disciplines. Be sure to see the surface of the cliff above the temple. The mountain is famous as the dwelling place of seven kinds of sacred birds. Legend states that the temple was donated to Kobo Daishi by a mysterious female recluse named Hokke-Sennin. Was she a shamaness or just a woman well advanced in Buddhist training? [We may never know.] Kobo Daishi carved two statues of Fudo, one in stone and kept in a cave at the rear of the temple, and the other in wood and enshrined in the hondo. By keeping the stone statue in the cave, Kobo Daishi ensured that the entire mountain needed to be worshipped in order to worship the statue. This way the mountain remained sacred, just as it had been in Shintoism. Over time, every nook and cranny of the mountain became sacred and every rock and slope became part of the sacred object. O

O n the way up you pass remarkable sets of Jizo statuary, which had been constant companions on the way. Jizo is a bosatsu (bodhisattva), a god? an entity? who has achieved nirvana but who chooses instead to provide assistance to others, in this case being the protector of many types of people including travellers, pregnant mothers, and in modern Japan in particular, the guardian of unborn, aborted, miscarried and stillborn babies. Jizo appear in many forms often decorated with bibs or hats. People who have lost children or who are seeking help for those who are sick, dress up the statues to keep them warm believing that if they clothe Jizo, so too will Jizo clothe their children in his warm robe of kindness and shelter them in his capacious sleeves. However expressed, there is something utterly poignant about this.

n the way up you pass remarkable sets of Jizo statuary, which had been constant companions on the way. Jizo is a bosatsu (bodhisattva), a god? an entity? who has achieved nirvana but who chooses instead to provide assistance to others, in this case being the protector of many types of people including travellers, pregnant mothers, and in modern Japan in particular, the guardian of unborn, aborted, miscarried and stillborn babies. Jizo appear in many forms often decorated with bibs or hats. People who have lost children or who are seeking help for those who are sick, dress up the statues to keep them warm believing that if they clothe Jizo, so too will Jizo clothe their children in his warm robe of kindness and shelter them in his capacious sleeves. However expressed, there is something utterly poignant about this. A

A bove the temple is one of many caves nearby where monks have meditated for centuries. I climbed up to look at walls covered with coins and other offerings, but mostly coins.

bove the temple is one of many caves nearby where monks have meditated for centuries. I climbed up to look at walls covered with coins and other offerings, but mostly coins.

‘Every nook and cranny of the mountain became sacred’ and every nook and cranny of the mountain was covered with interesting things to examine, as well as a maze of tracks which somehow didn’t seem to disturb its transfixing beauty. We deviated from the instructions but this splendid day there didn’t seem to be any wrong turns. We were climbing quite hard but it scarcely seemed noticeable. Transcendence? Sure. In its own way. When we reached the top there was a kilometre or two of plateau frequently with a sheer drop on one side of the track. Long views would suddenly unfold especially on the next descent. Glorious glorious walking.

When we reached the top there was a kilometre or two of plateau frequently with a sheer drop on one side of the track. Long views would suddenly unfold especially on the next descent. Glorious glorious walking. W

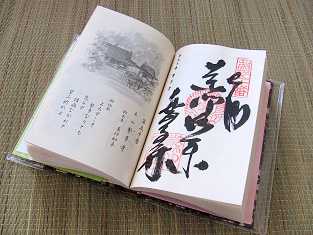

W e were sitting up in the air maundering our way through lunch complemented by some new discoveries from the Matsuyama shopping arcade, when I got the white book out again and realised it was going to be another rush to get to our bus. If we missed the one we’d set ourselves for the next one would get us home around 8.00, too late. So down through the paddies at pace and through the town of Fusuwara. We got two lots of additional advice about where the track restarted. Both were correct in their own way but incomplete costing us about 20 minutes. 2.3 the sign said when we got back on track, then 1.4 after that and, with a very steep and slippery climb included, 50 minutes to do it in. This colours the experience.

e were sitting up in the air maundering our way through lunch complemented by some new discoveries from the Matsuyama shopping arcade, when I got the white book out again and realised it was going to be another rush to get to our bus. If we missed the one we’d set ourselves for the next one would get us home around 8.00, too late. So down through the paddies at pace and through the town of Fusuwara. We got two lots of additional advice about where the track restarted. Both were correct in their own way but incomplete costing us about 20 minutes. 2.3 the sign said when we got back on track, then 1.4 after that and, with a very steep and slippery climb included, 50 minutes to do it in. This colours the experience.

As things stood, after climbing very hard for about 20 minutes we topped out and had a steepish descent: steps, cobbles, following a concreted creek, in mud — all that. We saw the day’s second temple, Daiho-ji, Great Treasure Temple, Number 44, but didn’t stay. We had a bus to catch. We arrived a bit sweaty but deeply content at 15.38 for 15.42, four minutes, just time to breach the vending machine. This had been a fabulous (half) day’s walking. I would like to do it again, more slowly.

As things stood, after climbing very hard for about 20 minutes we topped out and had a steepish descent: steps, cobbles, following a concreted creek, in mud — all that. We saw the day’s second temple, Daiho-ji, Great Treasure Temple, Number 44, but didn’t stay. We had a bus to catch. We arrived a bit sweaty but deeply content at 15.38 for 15.42, four minutes, just time to breach the vending machine. This had been a fabulous (half) day’s walking. I would like to do it again, more slowly.

The arcade was quiet on our return. It was Monday and all the tourists had gone back to work. We went straight to the front of the line for the softu crema, orange this time and magnificent. (Oh dear. A theme. However it sounds, we did do more than eat softu crema and drink vending machine coffee.) Manifold interesting types of fish for dinner including this chap. They have very fine cooks at the Sachiya Ryokan.

Last day. Culturally crippled as I am, there was a fleeting feeling that a bed off the floor and something other than rice, tofu and fish for breakfast would be nice. Just a hint. And lo and behold, our hosts had worked out what we had liked and what we had left for the previous breakfast and tailored the menu accordingly.

‘As with yesterday, please check carefully that you board the correct bus.’ We returned to the Okaido bus stop not actually brimming with confidence but we had been there before, we knew where the Starbucks was and where to sit to inhale the passing parade, and took the wrong bus. Wrong-ish. It was an Iyotetsu bus. It arrived at 9.33. I asked a bystander if it went to Niihama. He said sure. I asked the driver if he stopped at Ooto. He said sure. What are you going to do?

So, great. We’d got on the tour of the hospitals and community facilities of south-eastern Matsuyama bus. First stop the Cancer Centre, next stop the Matsuyamajoto Hospital, then the University Hospital, then an old folks centre. Only faintly troubled, we watched the aged and infirm emptying the seats. I tried the driver again. ‘Ooto?’ which might sound something like ‘oor-ooor-tee-orh’ and I wasn’t confident I had it down. He nodded reassuringly so we sat tight and, wrong bus right outcome, we did get there but 20 minutes after the appointed time. The appointment was with a taxi to allow us to miss another two-hour crawl up the bottom of a mountain. Time was important today because we had reserved train tickets to take us all the way back across the island to Takamatsu. And voila. Bless him. Another day in the forest and another very stiff climb. Writing about it in my journal that night I began: Maybe I’m too tired to write about this. It was just hard work right from the start, unrelenting.

Another day in the forest and another very stiff climb. Writing about it in my journal that night I began: Maybe I’m too tired to write about this. It was just hard work right from the start, unrelenting.

Yes. This one. (With the merest hint of a General Teaching Council of Scotland paperweight Ivor.) But you might notice that once we had reached and enjoyed Yokomine-ji, Flat Peak Temple, Number 60, it was downhill all the way. Somewhere down here on the far distant flat was our station. One of the issues was that there kept being things to look at and enjoy, like these ancient man-made dirt ‘bridges’ between two humps …

One of the issues was that there kept being things to look at and enjoy, like these ancient man-made dirt ‘bridges’ between two humps … hollowed out versions of the track, here on a detour that extended the journey …

hollowed out versions of the track, here on a detour that extended the journey … and wandering down embedded stone steps while being assailed with constant birdsong.

and wandering down embedded stone steps while being assailed with constant birdsong. This too was great walking. And we didn’t want to miss anything. While you’re there … So we got off the track to visit Koon-ji Oku-no-in, Koon-ji temple’s ‘hidden inner sanctuary’. (Oku, 奥, with whom we were travelling, of course insist you visit it.) And how could you miss this?

This too was great walking. And we didn’t want to miss anything. While you’re there … So we got off the track to visit Koon-ji Oku-no-in, Koon-ji temple’s ‘hidden inner sanctuary’. (Oku, 奥, with whom we were travelling, of course insist you visit it.) And how could you miss this? Fudo Myo-o at top with Kongara and Seitaka.

Fudo Myo-o at top with Kongara and Seitaka.

At 19, Mongaku experiences a religious conversion to Buddhism. Leaving his job as a civil servant, he takes a vow of poverty and sets off to the mountains to live as a wandering monk. In order to express his devotion, he sets himself a variety of impossible tasks. First he lies in a field for eight days and nights tormented by the hot sun and the bites of flies and mosquitoes. Next he decides to make a pilgrimage to the Nachi waterfall where the god of the waterfall lives. He wades into the pool at the base of the freezing waterfall, vowing to stay there for 21 days reciting prayers to the saint Fudo. [Saint eh? That’s another idea.] After three days the monk’s numbed feet slip on the rocks and he is swept downstream. Rescued by a passing stranger, Mongaku is anything but appreciative. He yells at his rescuer and immediately wades back into the pond under the falls. Eight boys jump into rescue him but he fights them off. After three more days the monk is so weak he loses consciousness and slips under the water. Fudo sends his god-like boy servants Kongara and Seitaka to help. They use magic to insulate his body from the cold. After being heartened by Fudo’s interest and concern he returns to the water and remains there reciting prayers for 21 days. Later, full of holy indignation, he fights and subdues The Dragon King, a sea god responsible for the sea and its storms.

I’m not quite sure what we can draw from that, or how it might reflect on Japanese culture, although it may help to explain some of its television game shows: you know, the ones where you have to eat 100 cockroaches while surrounded by people screaming. But after this, Koon-ji itself, Fragrant Garden Temple, Number 61, and resembling a large office block from the Brutalist School of architecture was small beer, and we still had two trains to catch.

We were down in the town of Komatsucho by this stage with not much more than kilometre to go. Distracted by the boggled interest of some school kids, we weren’t quite sure how many right angle turns we’d made and asked a passing motorist for directions to the last temple, Hoju-ji, Preserved Treasure Temple, Number 62. She didn’t want to tell us. In a final gesture of ossetai she really really wanted to drive us there. But no, no way. Not today. We’d come this far and while trembling on the brink, we hadn’t tumbled over the train timetable precipice just yet. We turned a corner and in the far distance I could see a big traffic sign to the eki, which I knew was 100 metres from the temple. So we hustled along the footpath of a busy main road to find a good deal of Hoju-ji in the middle of major building works. The contemporary world will intrude.

We were down in the town of Komatsucho by this stage with not much more than kilometre to go. Distracted by the boggled interest of some school kids, we weren’t quite sure how many right angle turns we’d made and asked a passing motorist for directions to the last temple, Hoju-ji, Preserved Treasure Temple, Number 62. She didn’t want to tell us. In a final gesture of ossetai she really really wanted to drive us there. But no, no way. Not today. We’d come this far and while trembling on the brink, we hadn’t tumbled over the train timetable precipice just yet. We turned a corner and in the far distance I could see a big traffic sign to the eki, which I knew was 100 metres from the temple. So we hustled along the footpath of a busy main road to find a good deal of Hoju-ji in the middle of major building works. The contemporary world will intrude.

And yes … with just enough time to tackle the vending machines.

with just enough time to tackle the vending machines.

••••

Did we get sick of temples? No. There are half a dozen more I’d really like to see including Number 88. Did we find them all interesting? No. It varied. But almost always. Shosun-ji, Iwaya-ji and Tairyu-ji I am unlikely to forget, not for the pain but for the reward of getting to them. Did we become pilgrims? No. We were just walkers having a red hot time. In terms of background, do I wish I knew then what I know now? Mmm … moot point. Not sure. It’s a bit like track notes. They never make sense till after you’ve done the walk. But there is nothing which sustains liveliness of mind more than the joy of initial discovery. Do I wish I had known more about temple etiquette? Yes. You light your joss sticks in threes and ring the bell once only. Anything a) less and b) more is egregious.

Myrna says:

It was like solving a puzzle every day. That’s the pilgrimage.

We ate outstanding apples, and great rice crackers. The white bait was full of flavour and life. We appreciated water. That’s the pilgrimage too.

As you go up into the mountains, with the effort and focus of the climbing and the constant presence of the natural world, the daily concerns of life just fall away. You are reminded of this by all those jizos which represent so much pain, parents struggling to lighten the weight of their sadness. Then you get to a temple garden and there is stillness and peace in the beauty, peace stopping the usual hurly burly of your mind. It’s not the religion or the ritual or the statues or the temples; it’s the experience. That’s the pilgrimage.

The next morning we found ourselves on a train heading further west along the northern coast of Shikoku. It was a late-ish departure and we’d spent part of the wait in Kotohira at the Palanquin, a tiny establishment devoted to coffee and sandwiches, thick with smoke and rarely I think patronised by non-Japanese. We were treated with glee and lavish assistance.

The next morning we found ourselves on a train heading further west along the northern coast of Shikoku. It was a late-ish departure and we’d spent part of the wait in Kotohira at the Palanquin, a tiny establishment devoted to coffee and sandwiches, thick with smoke and rarely I think patronised by non-Japanese. We were treated with glee and lavish assistance.  We did get the right bus — however short the trip that is a prerequisite — and got off at the right stop somewhere in the middle of the countryside and walked back the way we had come to Taisan-ji, Tall Mountain Temple, Number 56. The temple itself was not of great interest, but its siting was. It felt just a bit like being in another world, a possible product of too many trains and buses.

We did get the right bus — however short the trip that is a prerequisite — and got off at the right stop somewhere in the middle of the countryside and walked back the way we had come to Taisan-ji, Tall Mountain Temple, Number 56. The temple itself was not of great interest, but its siting was. It felt just a bit like being in another world, a possible product of too many trains and buses.  I liked this rock with its colourful striations. The small pine next to it is believed to cure all lower back ailments.

I liked this rock with its colourful striations. The small pine next to it is believed to cure all lower back ailments.

A mini version perhaps of the famous guardians of Senso-ji in Asakusa (eastern Tokyo). If so, they are Fujin the god of wind and Raijin the god of thunder. The road looked the easier option, but I had eaten the cakes and needed to perform some act of contrition. We made our peace with these chaps and headed through. Our progress was interrupted by some people in a car desperate to provide ossetai who, poor things, had to chase us 80 or so metres up some of the steepest and slipperiest steps going round. What was it? Bottles of drink, some crisps and lolly bars.

A mini version perhaps of the famous guardians of Senso-ji in Asakusa (eastern Tokyo). If so, they are Fujin the god of wind and Raijin the god of thunder. The road looked the easier option, but I had eaten the cakes and needed to perform some act of contrition. We made our peace with these chaps and headed through. Our progress was interrupted by some people in a car desperate to provide ossetai who, poor things, had to chase us 80 or so metres up some of the steepest and slipperiest steps going round. What was it? Bottles of drink, some crisps and lolly bars.  We continued on 200 more metres making extensive use of the handrail, where there was one. That’s the ascent, the final 280 metres. What an entry. And we landed head first into thick fog.

We continued on 200 more metres making extensive use of the handrail, where there was one. That’s the ascent, the final 280 metres. What an entry. And we landed head first into thick fog. We were staying here at the shukubo

We were staying here at the shukubo

I woke at 5.00,

I woke at 5.00,  Except for these guys — the number of Japanese, in Ehime at least, it takes to dig a hole on a Sunday morning.

Except for these guys — the number of Japanese, in Ehime at least, it takes to dig a hole on a Sunday morning.

It was only couple of k.s to the station and they took us along a concreted canal which probably once would have been a creek, past tennis training where the Nishikoris of the future were playing very capably, four or even six to a court, past a school where band practice was in full swing and soccer and dance practice were vying for space in the yard. One of the complaints of foreign teachers working in Japan is that they work a seven-day week, 50 or more weeks a year, including summer camp supervision. To do less is to display lack of commitment.

It was only couple of k.s to the station and they took us along a concreted canal which probably once would have been a creek, past tennis training where the Nishikoris of the future were playing very capably, four or even six to a court, past a school where band practice was in full swing and soccer and dance practice were vying for space in the yard. One of the complaints of foreign teachers working in Japan is that they work a seven-day week, 50 or more weeks a year, including summer camp supervision. To do less is to display lack of commitment.

and just as close to a shopping arcade with black sesame softu crema, I was thinking about where we were and what had been happening — no bird’s eye, no shape, bobbing up out the ground hither and thither. I was finding its intricacy understandable but slightly wearing. Yesterday, we had been negotiating our way round a mountaintop temple. Today, in the heart of a tourist destination, choosing between a Lawson and Willie Winkie for coffee, eating an astonishing variety of food, encountering major variations in landscape … But then I thought maybe the medium is the message. This is how it is. This is what we were up for. If in some moments, and they were only moments, it was overwhelming, it was also unforgettable.

and just as close to a shopping arcade with black sesame softu crema, I was thinking about where we were and what had been happening — no bird’s eye, no shape, bobbing up out the ground hither and thither. I was finding its intricacy understandable but slightly wearing. Yesterday, we had been negotiating our way round a mountaintop temple. Today, in the heart of a tourist destination, choosing between a Lawson and Willie Winkie for coffee, eating an astonishing variety of food, encountering major variations in landscape … But then I thought maybe the medium is the message. This is how it is. This is what we were up for. If in some moments, and they were only moments, it was overwhelming, it was also unforgettable. We had passed the Scrivener Department of the Ehime Prefecture Canal System and The Gright, billed in English as: ‘

We had passed the Scrivener Department of the Ehime Prefecture Canal System and The Gright, billed in English as: ‘ We were welcomed by another champion of the hospitality industry.

We were welcomed by another champion of the hospitality industry.

Sunday afternoon, and it was seething with o-henro and other tourists, a busload of Spaniards amongst them, who were behaving more egregiously than us at our worst. We were in town. The city gardens were on top of a hill which provided excellent views of the city and I had my bird’s eye view. We had passed the Dogo Onsen complex and stumbled over the Botchan Karakuri Clock, Botchan being a popular novel written by local Natsume Soseki and widely read by Japanese school children. On the hour the characters emerge and do their clockwork thing, delightfully, and then it all folds away till next time.

Sunday afternoon, and it was seething with o-henro and other tourists, a busload of Spaniards amongst them, who were behaving more egregiously than us at our worst. We were in town. The city gardens were on top of a hill which provided excellent views of the city and I had my bird’s eye view. We had passed the Dogo Onsen complex and stumbled over the Botchan Karakuri Clock, Botchan being a popular novel written by local Natsume Soseki and widely read by Japanese school children. On the hour the characters emerge and do their clockwork thing, delightfully, and then it all folds away till next time. At its base is a trough fed by a mineral spring for walkers to salve their weary feet, before heading off to the very fine onsen and

At its base is a trough fed by a mineral spring for walkers to salve their weary feet, before heading off to the very fine onsen and  Day 4. I didn’t really feel like I look. Just caught the moment. It had been a great day’s walking and I was actually ready for more, but we were shortly about to get off the mountain via cable car, ropeway in the vernacular. It was another nansho temple, Tairyu-ji, Grand Dragon Temple, Number 21.

Day 4. I didn’t really feel like I look. Just caught the moment. It had been a great day’s walking and I was actually ready for more, but we were shortly about to get off the mountain via cable car, ropeway in the vernacular. It was another nansho temple, Tairyu-ji, Grand Dragon Temple, Number 21. bus driver had dropped us off with 450m to climb in a bit over 3km, 1 in 6. That’s about what it felt like, but we were up for it that day. It was a lovely path winding through forest and we began with a preliminary reward.

bus driver had dropped us off with 450m to climb in a bit over 3km, 1 in 6. That’s about what it felt like, but we were up for it that day. It was a lovely path winding through forest and we began with a preliminary reward.

After a short look round on this peak there was a long but straightforward descent which just kept unfolding in its loveliness. Near this point we walked through a serious and extensive collection of bonsai and met the gentleman who enquired about the health of Murray Rose. His group of o-henro were having a congenial but lively squabble about directions. Newly seasoned and knowledgable etc etc, we were able to point them in the direction from where we had just come.

After a short look round on this peak there was a long but straightforward descent which just kept unfolding in its loveliness. Near this point we walked through a serious and extensive collection of bonsai and met the gentleman who enquired about the health of Murray Rose. His group of o-henro were having a congenial but lively squabble about directions. Newly seasoned and knowledgable etc etc, we were able to point them in the direction from where we had just come.

The Nakagawa River, famed for the clarity of its water but on this day an opaque icey aqua, was at the foot of this descent. Across this bridge the next climb began. For half of the way, this one stayed on a tarred road, very narrow — just trafficable if you were driving a Japanese little car or van — following a creek valley up the hill. Uphill but only vehicle grade.

The Nakagawa River, famed for the clarity of its water but on this day an opaque icey aqua, was at the foot of this descent. Across this bridge the next climb began. For half of the way, this one stayed on a tarred road, very narrow — just trafficable if you were driving a Japanese little car or van — following a creek valley up the hill. Uphill but only vehicle grade.  Easy walking even meeting this friend on the way. The road led to a disused farm where this oddity appeared.

Easy walking even meeting this friend on the way. The road led to a disused farm where this oddity appeared.

As customary, just to keep you honest and remind you of a few salient things, the big climb is supplemented by several sets of steps. Tairyu-ji was being repaired but that didn’t interfere with its complexity and beauty. It is suggested that Kobo Daishi sat on a rock peak near here to practice Kokuzo Gumonji-ho, a short mantra. To pray for improved memory this mantra must be repeated a million times over the course of 100 days. You’d probably remember that at least even if nothing else.

As customary, just to keep you honest and remind you of a few salient things, the big climb is supplemented by several sets of steps. Tairyu-ji was being repaired but that didn’t interfere with its complexity and beauty. It is suggested that Kobo Daishi sat on a rock peak near here to practice Kokuzo Gumonji-ho, a short mantra. To pray for improved memory this mantra must be repeated a million times over the course of 100 days. You’d probably remember that at least even if nothing else. At the ropeway station we were offered and gratefully accepted a cup of mushroom soup and paid startlingly reduced fares: a version of ossetai for overseas visitors perhaps. All sorts of things were promised of the view on the 15 minute journey down but in thick cloud we saw nothing till the Nakagawa suddenly came into focus just below us. We found a Lawson (ubiquitous convenience store chain) which provided coffee and a snack and we found the bus which would take us back to Tokushima. It was full of school kids, about 30 of them, whose hot breath and damp clothes fogged up the windows instantly which is how those windows remained for the hour and a quarter of the trip. We got on at Wajiki East which sounds as downtown as it was. The terminus of the ropeway was the only real built feature and yet here come all these kids. From where? And going past how many schools in 75 minutes on the bus towards Tokushima? And anyway, doesn’t Tokushima itself have schools? Thirteen train stations, no schools?

At the ropeway station we were offered and gratefully accepted a cup of mushroom soup and paid startlingly reduced fares: a version of ossetai for overseas visitors perhaps. All sorts of things were promised of the view on the 15 minute journey down but in thick cloud we saw nothing till the Nakagawa suddenly came into focus just below us. We found a Lawson (ubiquitous convenience store chain) which provided coffee and a snack and we found the bus which would take us back to Tokushima. It was full of school kids, about 30 of them, whose hot breath and damp clothes fogged up the windows instantly which is how those windows remained for the hour and a quarter of the trip. We got on at Wajiki East which sounds as downtown as it was. The terminus of the ropeway was the only real built feature and yet here come all these kids. From where? And going past how many schools in 75 minutes on the bus towards Tokushima? And anyway, doesn’t Tokushima itself have schools? Thirteen train stations, no schools? Half slept; this was a standard journey. The groovy girls in the back seat did their phones. We got back to Subaruyado Yoshino (the ‘Pleiades Ryokan’: subaru=constellation) to be accosted again by very good food in vast quantities, and a long and exhausting conversation in a combination of those well known languages Google translation and charade.

Half slept; this was a standard journey. The groovy girls in the back seat did their phones. We got back to Subaruyado Yoshino (the ‘Pleiades Ryokan’: subaru=constellation) to be accosted again by very good food in vast quantities, and a long and exhausting conversation in a combination of those well known languages Google translation and charade.

Shiromine-ji, White Peak Temple, Number 81, was a fascinating place with at least three major layers of buildings in the middle of very highly developed gardens. At the entry we were welcomed by this collection of maneki-neko, and then there were goats and chooks and sheep and birds and monkeys. And this chap. No idea who or what he is, but there will be a story. There always is.

Shiromine-ji, White Peak Temple, Number 81, was a fascinating place with at least three major layers of buildings in the middle of very highly developed gardens. At the entry we were welcomed by this collection of maneki-neko, and then there were goats and chooks and sheep and birds and monkeys. And this chap. No idea who or what he is, but there will be a story. There always is.

This is also where my camera lens decided to stick on the limits of its digital zoom. This is the last picture it took — from about 40m away.

This is also where my camera lens decided to stick on the limits of its digital zoom. This is the last picture it took — from about 40m away.

Those instructions claimed that our accommodation was six minutes walk from the station. It might have taken us nine. Maybe 15. No disaster. We were the only customers at Kotobuki (Congratulations! or Long life!), sank into its bath and ate one of the really great Japanese meals ever. This wasn’t perfect classical cooking. We had some of that at Matsuyama and applauded it roundly. This was a meal cooked by people who have a deep-seated understanding coming from the very marrow of their bones for what would be interesting and tasty. They proved themselves to be wonderful hosts in any number of ways.

Those instructions claimed that our accommodation was six minutes walk from the station. It might have taken us nine. Maybe 15. No disaster. We were the only customers at Kotobuki (Congratulations! or Long life!), sank into its bath and ate one of the really great Japanese meals ever. This wasn’t perfect classical cooking. We had some of that at Matsuyama and applauded it roundly. This was a meal cooked by people who have a deep-seated understanding coming from the very marrow of their bones for what would be interesting and tasty. They proved themselves to be wonderful hosts in any number of ways.

We went to see the Sheath Bridge. This is the information I have about it: ‘Year is a bridge that God is in you over only once. Since a little away from the approach you can see people even less slowly. It can not be over, but I recommend enjoy the view.’ Challenging, but I think — God is in the bridge. You can only cross it once (a year?). It’s locked up the rest of the time. But it’s good to look at. I’ve also found a story about a demigod who had all his toes cut off and therefore made sheaths for his feet which came off while fleeing from an army of monkeys. Take your pick really.

We went to see the Sheath Bridge. This is the information I have about it: ‘Year is a bridge that God is in you over only once. Since a little away from the approach you can see people even less slowly. It can not be over, but I recommend enjoy the view.’ Challenging, but I think — God is in the bridge. You can only cross it once (a year?). It’s locked up the rest of the time. But it’s good to look at. I’ve also found a story about a demigod who had all his toes cut off and therefore made sheaths for his feet which came off while fleeing from an army of monkeys. Take your pick really.  Konpira-san is the largest Shinto shrine on Shikoku and that’s the main reason for visiting the town of Kotohira. Its population is officially about 10,000, although I don’t know where you would put the city limits. On the flat side of the main drag it’s heavily populated semi-agricultural land which covers a considerable plain.

Konpira-san is the largest Shinto shrine on Shikoku and that’s the main reason for visiting the town of Kotohira. Its population is officially about 10,000, although I don’t know where you would put the city limits. On the flat side of the main drag it’s heavily populated semi-agricultural land which covers a considerable plain.

I’ve seen bigger wisteria plants but this one was enormous and, in flower, has five colours. We had a look around and like anything built into the forest wall this temple had its charms. I rang the bell and murmured a request for good fortune, found the track opening and off went. Up up up.

I’ve seen bigger wisteria plants but this one was enormous and, in flower, has five colours. We had a look around and like anything built into the forest wall this temple had its charms. I rang the bell and murmured a request for good fortune, found the track opening and off went. Up up up. Note the fall off to the left. We quite often found ourselves walking next to a sheer but quite heavily forested drop. The pad would be running round the lip of small plateaux. Splendid walking. We got to Choudoan Temple, not one of the 88, but the peak of the first climb and ate one of our volley ball-sized apples and some rice crackers, discovering that the packet was a quarter full of dried whitebait. Japan. It was hot, round 30C and fairly sticky. My clothes were wringing wet.

Note the fall off to the left. We quite often found ourselves walking next to a sheer but quite heavily forested drop. The pad would be running round the lip of small plateaux. Splendid walking. We got to Choudoan Temple, not one of the 88, but the peak of the first climb and ate one of our volley ball-sized apples and some rice crackers, discovering that the packet was a quarter full of dried whitebait. Japan. It was hot, round 30C and fairly sticky. My clothes were wringing wet.

In

In

The last big climb was an effort. I remember we passed a group of six middle-aged women o-henro, and flopping at a rest area with some chocolate and resisting the temptation to finish off our water — not much else. There is no photographic evidence of anything till we get to Shosan-ji which itself provides 20 minutes worth of false dawns. You hit the

The last big climb was an effort. I remember we passed a group of six middle-aged women o-henro, and flopping at a rest area with some chocolate and resisting the temptation to finish off our water — not much else. There is no photographic evidence of anything till we get to Shosan-ji which itself provides 20 minutes worth of false dawns. You hit the  made road and think you’re there. Then the distance signage goes a bit weird. Another kilometre just drops in from thin air. It looks domestic when you get to the wonderful entree of a fenced path with scores of stone lanterns and start being entertained by a dozen or so huge bosatsu, but there’s still quite bit to go.

made road and think you’re there. Then the distance signage goes a bit weird. Another kilometre just drops in from thin air. It looks domestic when you get to the wonderful entree of a fenced path with scores of stone lanterns and start being entertained by a dozen or so huge bosatsu, but there’s still quite bit to go. T

T

It looked easy. We found bits of the road and were supposed to find short tracks to cut across the huge hairpins. Some we found and some we didn’t, ending up in a sort of shadow game with a young pilgrim both of us assuming the other knew where they were going. I was holding our map ostentatiously, but like all maps at this time of day we were about a kilometre behind where I thought we were. We stopped the shadow game, had a yarn, told him where we wanted to go and he zipped off at speed. (He hadn’t done the climb from Number 11.) In a few minutes he was waving and pointing. He’d found our minshuku (big b&b, small guest house). Arigato, my friend wherever you are. Arigato.

It looked easy. We found bits of the road and were supposed to find short tracks to cut across the huge hairpins. Some we found and some we didn’t, ending up in a sort of shadow game with a young pilgrim both of us assuming the other knew where they were going. I was holding our map ostentatiously, but like all maps at this time of day we were about a kilometre behind where I thought we were. We stopped the shadow game, had a yarn, told him where we wanted to go and he zipped off at speed. (He hadn’t done the climb from Number 11.) In a few minutes he was waving and pointing. He’d found our minshuku (big b&b, small guest house). Arigato, my friend wherever you are. Arigato. I would do none of those things usually, and our hosts were extremely gracious and forgiving, cooking us a terrific meal. However two middle-aged, gimlet-eyed female guests were monitoring our every move to see what infamy we (Myrna was in this too. She washed her clothes in a hand basin and wanted to leave them to drip on the tatami!) would commit next, and the intake of breath when I staggered off the verandah in my indoor shoes was like the hissing of a snake.

I would do none of those things usually, and our hosts were extremely gracious and forgiving, cooking us a terrific meal. However two middle-aged, gimlet-eyed female guests were monitoring our every move to see what infamy we (Myrna was in this too. She washed her clothes in a hand basin and wanted to leave them to drip on the tatami!) would commit next, and the intake of breath when I staggered off the verandah in my indoor shoes was like the hissing of a snake. I watched the kids going to school and examined a remarkable sport-proof fence 15m high that surrounded the playing field with an ingenious system of stiffening by cables with zig-zag buttressing. And with the gracious assistance of a stonemason’s products, I studied up the day.

I watched the kids going to school and examined a remarkable sport-proof fence 15m high that surrounded the playing field with an ingenious system of stiffening by cables with zig-zag buttressing. And with the gracious assistance of a stonemason’s products, I studied up the day.

We got off at Number 13 Dainichi-ji, The Temple of the Supreme Buddha Dainichi. It had lots to interest us and lots of 0-henro action for mid morning. Its accessibility on a main road may have been a factor, but it also has this rather striking statue of the bosatsu Kannon, the goddess of mercy, enclosed in prayerful hands. Several pilgrims took our photo; it must have been a slow day shutter-wise.

We got off at Number 13 Dainichi-ji, The Temple of the Supreme Buddha Dainichi. It had lots to interest us and lots of 0-henro action for mid morning. Its accessibility on a main road may have been a factor, but it also has this rather striking statue of the bosatsu Kannon, the goddess of mercy, enclosed in prayerful hands. Several pilgrims took our photo; it must have been a slow day shutter-wise. Over the road was the Ichinomiya Jinja, a major Shinto shrine with big horses and a large stone construction which suggested Shinto’s animist roots. In addition in this photo you can almost see the entrance to the Ichinomiya Castle ruins, to the path up to them anyway.

Over the road was the Ichinomiya Jinja, a major Shinto shrine with big horses and a large stone construction which suggested Shinto’s animist roots. In addition in this photo you can almost see the entrance to the Ichinomiya Castle ruins, to the path up to them anyway.  The track would take us through the those paddies, across the bridge, through the intersection of the two green hills in the mid ground and eventually to Tokushima in the far distance. Several temples were bedded in the back of the hill on the left. It all looks so easy.

The track would take us through the those paddies, across the bridge, through the intersection of the two green hills in the mid ground and eventually to Tokushima in the far distance. Several temples were bedded in the back of the hill on the left. It all looks so easy.

is on or near archaeological remains of the original and just as the guide book says, it exudes age and atmosphere.

is on or near archaeological remains of the original and just as the guide book says, it exudes age and atmosphere. A great deal of the imagery and statuary we saw was concerned with the protection of the health and welfare of children. Placing a bib on the infant is a worshipful act reflecting a specific or general request for care or intervention.

A great deal of the imagery and statuary we saw was concerned with the protection of the health and welfare of children. Placing a bib on the infant is a worshipful act reflecting a specific or general request for care or intervention.

I thought about it. Even as souvenirs, but of what? Wouldn’t it just be a version of fancy dress? Most unsuitable for what the vast majority of pilgrims treat as a most serious undertaking. As it happens I was so discombobulated I didn’t even buy a guide book which, despite having our inch-thick wad of paper from Oku to protect us, would have been a good idea. One dominant thought was that anything we didn’t eat we’d have to carry.

I thought about it. Even as souvenirs, but of what? Wouldn’t it just be a version of fancy dress? Most unsuitable for what the vast majority of pilgrims treat as a most serious undertaking. As it happens I was so discombobulated I didn’t even buy a guide book which, despite having our inch-thick wad of paper from Oku to protect us, would have been a good idea. One dominant thought was that anything we didn’t eat we’d have to carry.

which connect Honshu, an intermediate island called Awaji, and Shikoku, and got off where we were told to, Naruto Nishi bus stop, and sort of looked around. That first moment … I don’t care who you are, you’re just not with it.

which connect Honshu, an intermediate island called Awaji, and Shikoku, and got off where we were told to, Naruto Nishi bus stop, and sort of looked around. That first moment … I don’t care who you are, you’re just not with it.  We found the stone steps as required and shot up them, well past the metal gate (as specified) which would take us through the German Forest, a war memorial that you mightn’t have imagined being there. A couple of turns to find a main road and walk along it for 420m. (

We found the stone steps as required and shot up them, well past the metal gate (as specified) which would take us through the German Forest, a war memorial that you mightn’t have imagined being there. A couple of turns to find a main road and walk along it for 420m. (

noticing the little red and white pilgrims which so helpfully marked the way. Motion; and this track of course was easy. If you couldn’t get from Temple One to Temples Two and Three you simply wouldn’t be trying.

noticing the little red and white pilgrims which so helpfully marked the way. Motion; and this track of course was easy. If you couldn’t get from Temple One to Temples Two and Three you simply wouldn’t be trying.

As so often, the temple complex was embedded in a very pleasant garden full of enticing mysteries. I never unravelled most of these, but you could begin developing your own constructions of it all.

As so often, the temple complex was embedded in a very pleasant garden full of enticing mysteries. I never unravelled most of these, but you could begin developing your own constructions of it all.  For example, at left are bussokuseki, forms of very ancient Buddhist icons from a period when icons of the Buddha were forbidden. (‘Thou shalt have no graven images.’ There is obviously an urge to make the ineffable visible and concrete which has a huge impact on the practice of any religion. Humans are easily distractible.)

For example, at left are bussokuseki, forms of very ancient Buddhist icons from a period when icons of the Buddha were forbidden. (‘Thou shalt have no graven images.’ There is obviously an urge to make the ineffable visible and concrete which has a huge impact on the practice of any religion. Humans are easily distractible.)

Born in 774AD a kilometre from the temple where we stayed on this first night, he is the founder of Shingon (True Word) Buddhism. His own enlightenment seems to have been derived, initially at least, from long periods spent in isolated mountain retreats chanting sutras. An exceptional student, he gained the trust of his Emperor and was included in a state mission to China, Xi’an in fact which is a long way from Tokushima City. The story goes that he completed a prodigious feat of learning there, memorising in 3 months what usually took 30 years, and came back to Japan to spread Esoteric Buddhism. Esoteric: abstruse, obscure, arcane, rarefied, recondite, abstract, difficult, perplexing, enigmatic, inscrutable. Why would you be spreading this? What sort of rod have you made for your own back? Other perspectives suggest that Shingon introduced or enhanced ritual (especially the use of mantras) in a religion that had focused on good works and personal action.

Born in 774AD a kilometre from the temple where we stayed on this first night, he is the founder of Shingon (True Word) Buddhism. His own enlightenment seems to have been derived, initially at least, from long periods spent in isolated mountain retreats chanting sutras. An exceptional student, he gained the trust of his Emperor and was included in a state mission to China, Xi’an in fact which is a long way from Tokushima City. The story goes that he completed a prodigious feat of learning there, memorising in 3 months what usually took 30 years, and came back to Japan to spread Esoteric Buddhism. Esoteric: abstruse, obscure, arcane, rarefied, recondite, abstract, difficult, perplexing, enigmatic, inscrutable. Why would you be spreading this? What sort of rod have you made for your own back? Other perspectives suggest that Shingon introduced or enhanced ritual (especially the use of mantras) in a religion that had focused on good works and personal action.

But where exactly? You are in the middle of a series of paddy fields after a long day and there appears little option but to place your fate in the hands of the almighty. However, the only other guy on the bus got off with us and while he hadn’t gone the full

But where exactly? You are in the middle of a series of paddy fields after a long day and there appears little option but to place your fate in the hands of the almighty. However, the only other guy on the bus got off with us and while he hadn’t gone the full

Q. on the internet: ‘Do Buddhists Worship Idols? A. Buddhists sometimes pay respect to images of the Buddha, not in worship, nor to ask for favours. A statue of the Buddha with hands rested gently in its lap and a compassionate smile reminds us to strive to develop peace and love within ourselves. Bowing to the statue is an expression of gratitude for the teaching.’

Q. on the internet: ‘Do Buddhists Worship Idols? A. Buddhists sometimes pay respect to images of the Buddha, not in worship, nor to ask for favours. A statue of the Buddha with hands rested gently in its lap and a compassionate smile reminds us to strive to develop peace and love within ourselves. Bowing to the statue is an expression of gratitude for the teaching.’