You know these three photos. Of course you do. Exceedingly well known. They are on Mr. AI’s list of the greatest of all time. But there are questions.

Raising the flag on Iwo Jima 1945: Joe Rosenthal

The first one, ‘Raising the flag’, has appeared on stamps, on a war bond, is memorialised in bronze as the national monument to the US Marines in Arlington, Virginia. Etc. Etc. It won a Pulitzer Prize. The remaining flag raisers (two died in later fighting) were sent on tour through the length and breadth of their country although one who never wanted to go in the first place was sent home for drinking excessively. John Bradley identified as the man taking the lead in the front of the planting didn’t like talking about it much either, the main reason possibly being that he wasn’t there.

Here’s a pic of the flag actually being raised after the hill was captured.

Bit low key eh. The flag has been attached to a bit of metal pipe they found on the top on the hill. You could get a statue out of it but it would have its limitations.

Joe Rosenthal was there of course and tells a terrific story about it, a terrific American story really. But he wasn’t there. Not then. He came later in the day when they did it again with a much bigger flag. He may have posed the raisers.

Okay. So what? Does that matter? Well, too late really to be asking questions like that. What does ‘real’ mean anyway? The statue is up! And it’s a beauty.

The Falling Soldier 1936: Robert Capa

And ‘Falling Soldier’. Spanish Civil War during the Battle of Cerro Muriano. ‘A soldier [identified as Federico Garcia] at the very moment of his death. He is shown collapsing backward after being fatally shot in the head, with his rifle slipping out of his right hand.’

Like a lot of these photos it had a huge impact on publication (in Life magazine of course, on the cover). This is war. This is the good guys, or a good guy, being shot. Kafflooiie. Horror.

Capa has said: ‘I was there in the trench with about twenty milicianos [militiamen] … I just kind of put my camera above my head and even didn’t look and clicked the picture, when they moved over the trench. And that was all. … [T]hat camera which I hold above my head just caught a man at the moment when he was shot. That was probably the best picture I ever took.’

Hmmm … except it appears that the photo was taken at Espejo, a location about 50kms from where that battle was fought. Federico Garcia really did die at Cerro Muriano, but behind a tree. During this war photographers were granted no access to areas of live fighting. Many years later a suitcase full of Capa’s negatives was found none of which were of this photo but with scores of others apparently rehearsing the scene.

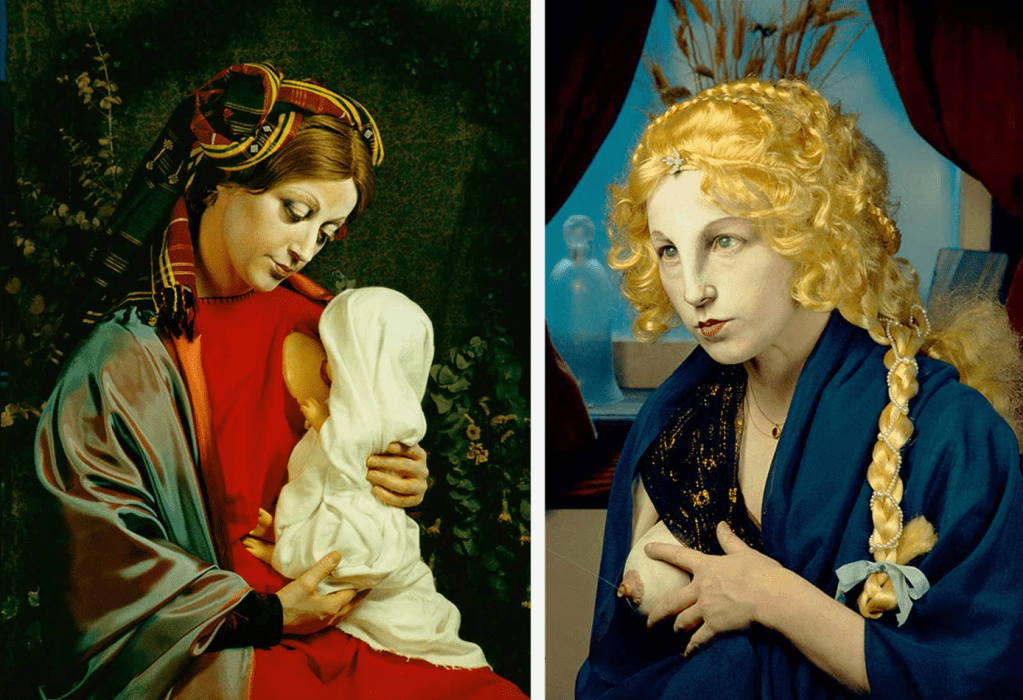

Does it matter? Does Cindy Sherman really look like this?

We know that Cindy is faking it. Whatever it might be she’s up to, it’s something else. In terms of our appreciation of the photos there is a different set of criteria operating. With ‘Raising the flag’ it probably doesn’t matter because Rosenthal has made such an excellent job of the tableau, and anyway it’s too late. The platoon has bolted. But ‘Falling soldier’ … is it such a great photo if it’s just a bloke falling over? It would seem to gain most all its strength from its authenticity and context. Without that …

Next question please.

Who took this photo?

Well it says ‘Nick Út’ doesn’t it? There. In the caption. You can find many many instances of him identified as its author. Near universal. He won a Pulitzer Prize for it — sometimes described as the most important image of Viet Nam’s ‘televised war’, World Press Photo’s Photo of the Year in 1973. What’s the question?

Well, one of these guys did and none of them are Nick Út.

Út was there, but only near there. ‘Based on images taken by and of Út that day, he would have had to sprint about 560ft forward, snap the famous photo, then run back 250ft, then turn around to be seen walking toward NBC News cameramen – “an extremely implausible scenario”.’

To find out what actually happened you can watch ‘The Stringer’ on Netflix or read The Guardian‘s take here. But it appears that Nguyễn Thành Nghệ, another photographer who was working as a driver that day, took the photo and sold it to Associated Press for $20 and a print. Carl Robinson, Associated Press’s photo editor on duty in Saigon that day alleges that Horst Faas, ‘the bureau’s legendarily domineering photo chief’, ordered him to change the image’s credit from the stringer to Út, the only AP staff photographer on site that day.

Interesting to know, but does that matter? Does the authorship impinge on the impact, on the ‘greatness’ of the photo?

I don’t really care — not really — who took it (although Mr. Nguyễn might), but I do think it suggests something about how photos become ‘great’. Generally you need your team working for you, a big, capable mainstream team (like AP). You need something to carve a path through the 18 million others. You need the cultural apparatus bent in your favour and, reviewing lists of ‘great photos’, it helps enormously if you’re American or American-sponsored.

We might have to begin again from the idea that great photos are also popular and well known. The egg of publicity may well, must, give birth to the chicken of perceived quality.

• • • • • • • • •

‘When I got back from Wattie Creek [the Dept of Aboriginal Affairs] got me to convert [the photo of Whitlam and Lingiari] to a black and white image’, Mr Mervyn Bishop notes. It wasn’t used anywhere until six months after the event, three months after the Whitlam government had been sacked. Even then it was tucked away inside the Aboriginal News, hardly a dominant mainstream publication. It was 10 years later that Kev Carmody, haunted by his memories of Merv’s pic, wrote ‘From Little Things Big Things Grow’ with Paul Kelly. It didn’t chart especially well. It did better in a version by The Get Up Mob in 2008.

It was when the song was performed in front of Merv’s photo projected on two giant screens at Gough’s memorial in Sydney Town Hall that the song and more particularly the photograph cemented their place in public life and esteem. In 2014. Thirty-nine years after it was taken.