This filing cabinet — a fine example of anachronism — has been itinerant since its originator died, never really finding a home. Perhaps I should say a truly welcoming home.

Four drawers full of (dadah!!) ‘The Anderson History’, it has had plenty of homes. After a period of periodic and occasionally enthusiastic stocking it stood dormant at Laurel Street where it was honoured through the idea rather than the active relationship, the idea being that in that pile, in there somewhere, would be nuggets, gold, revelation, the real story. Marion was sure. She had included all sorts of ephemera: not just lots of letters and photos, but invitations, forms, certificates and even a (small) bit of an aeroplane that had come home from the war. (See more below.)

It moved to Margaret Grove where, in my study, its top provided a place to leave empty coffee cups and bits of paper that weren’t immediately needed. Four drawers that might have been locked. There was an opportunity to do so. The lock is built in but almost astonishingly a key could always be found. However it remained largely unviolated. Myrna may have checked that there was actually something in there a time or two.

Then, after our shift, it went on a country jaunt to Ripon Road which was appropriate in some ways: Western District, biggish house, country comfort, a place given over to enterprise and tenacity. That would suit the broad thrust of the story still undisturbed inside its thin steel walls.

But it returned to the city and went north to Gloucester Street. Jessie said she wanted it … mmm did she say she wanted it? Might be a bit strong. Had room for it. This was the one time it was moved when death or the sale of its contemporary resting place was not involved.

But Jessie likes history, always has, so we could gently lever it onto her. And it could be her turn to make jokes about it. It went with her to Cowper Street. To say the cats enjoy it as a vantage point is true but not intended to sell her investigations short.

* * * * *

The idea of family history has a siren call. I’m sure one purpose is to elevate your self-esteem by finding some distant hero who might just be a relative with the same sort of nose as you. And by some distant hero I actually mean any number of distant heroes. Cartloads. All fascinating. And significant, highly significant. Let me offer an example, appropriately highlighted:

The clan produced not only poets, musicians and clerics. Duncan McRae was a noted warrior said to have defended practically single-handed the almost impregnable castle of Eilean Donan against the attack of 400 McDonald fighting men, killing their chief with his last arrow.

Colin Farquhar McRae, The McRae Heritage

Single-handed. Killed the chief with his last arrow! Just how cool is that?! You might like to meet me on that basis alone.

As a rule you don’t stop to think that William Anderson was the Member of the Legislative Assembly for Windermere in the first Victorian parliament. But when you do there are moods in which you might feel at least momentarily enriched.

Family history might also be useful to explain something about you: why you like dogs say, or your propensity to feel just a little bit Scandinavian.

But its real value might be the unexpected clicking into place of pieces, simple pieces not corners or edges, of a jigsaw providing a larger base of meaning to what you know about yourself. With reference to what might be found in those four drawers: who or what was Myrna? Naples as a surname? And Aldridge, was that a person? Why was the Anderson house in Horsham called ‘Pencloe’? And did the Browns really live at Jesmond? (Yes they did. The Walter/ Fallaws must have bought it from them.) J.C. Brown and his engineering works, what did they do? And was he the Mayor of Geelong, or was that his brother?

There have been people who have I have known who have had this knowledge as lived experience. They’ve talked it. (I’m only slightly embarrassed that I used to say, ‘I’m glazing over. I’m glazing over’ as the recitation of possible connections went on. ‘Joycie Jones. I think she was a …’)

And then there is the lens that domestic history provides for the undulations of larger historical events. Is that what happened? Did they notice? Did they react? What were they doing?

The piece of aeroplane mentioned above is in this photo along with a letter from one of the many David Andersons, in this case someone who would have been a great uncle to our girls. The letter says in part:

‘Dear Mother [Florence, who had both a sister/ best friend and a granddaughter called Myrna],

I have missed a week in writing to you, but you will see why later. Part was written at sea and a short note from here where we’ve now been a fortnight … . Haven’t done any work for seven weeks, so naturally will be slightly stale. … Apart from being on leave we have resided in a first class pub which is really our officers’ mess and is very comfortable. Of course there has been the usual reception, routine of records, issue of equipment etc. In our spare moments we have been to see the oldest church in England 11th century at Christchurch, etc. …’

It provides a happy story of tourism (loved the English countryside, hated the cities) and youthful larks. But it is a letter from the war, and a short while later there will be another letter explaining that Anderson D. C. RAAF was in plane which flew into the side of a Welsh mountain. Hence the aeroplane shard. The story builds itself out of parts and moves towards that ah yes … I get it, that’s what happened moment.

Another of the filing cabinet’s treasures — and I know this because it is, within a fairly narrow compass, quite famous and is allowed out for air from time to time — is a photo of Myrna’s mother (aforesaid Marion) at Longeranong (an agricultural college close to where she lived in Horsham) with the Land Army during the Second World War.

This photo is famous because, the story goes, she only went there once and the photographer put her on a tractor and took her photo because she was so good looking. There is plenty of evidence of the latter, clear wide smiling but slightly distant eyes with their own allure, insert acceptable synonym for shapely, hair that hadn’t been too deconstructed by the outdoor life (a little bit Chloe Sevigny perhaps?). But two other photos of all the Land Army girls have recently emerged and she’s there wearing different clothes each time so she could even have been a regular. Yesterday I found a certificate that confirms her appointment as a Lieutenant in the Land Army. You wouldn’t get that for your looks alone.

That’s the sort of thing you can check with the right sort of documentation. And the right sort of documentation was probably in that filing cabinet waiting for a diligent soul.

* * * * *

Jessie started working her way through its contents with great application. Stuff went to the Geelong Historical Society, the War Memorial Records, the State Library of Victoria, ‘Melbourne Royal’ which now runs the Royal Melbourne Show (a pamphlet of the program from the 1920s). And a certain amount to the bin. Files were established and she developed an actual familiarity with the contents. Bless her.

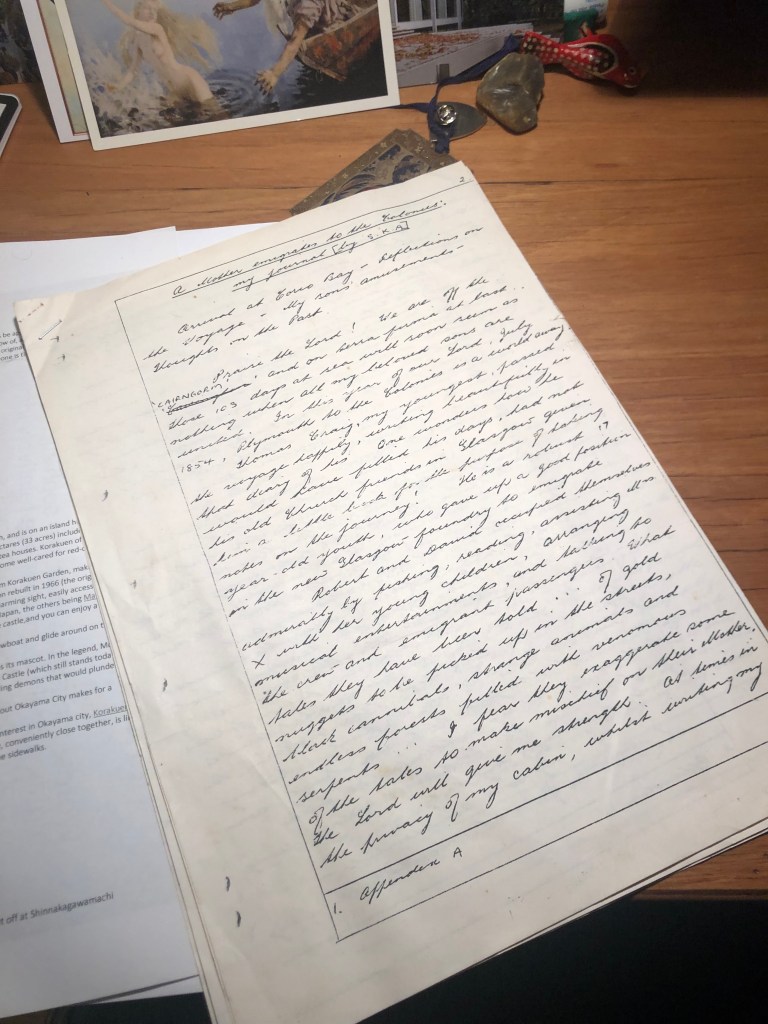

There was one item which showed quite a deal of promise, a first-hand account of the arrival and establishment of the Anderson family, Marion’s forebears.

It is a ten-page handwritten and photocopied document entitled A Mother Emigrates to the Colonies: My Journal [by S.K.A.]. And that would be Sarah Katherine Anderson, mother of the six quite formidable Anderson brothers. It was sometimes referred to as ‘The Letter’ which it isn’t; it is self-described as extracts from a journal.

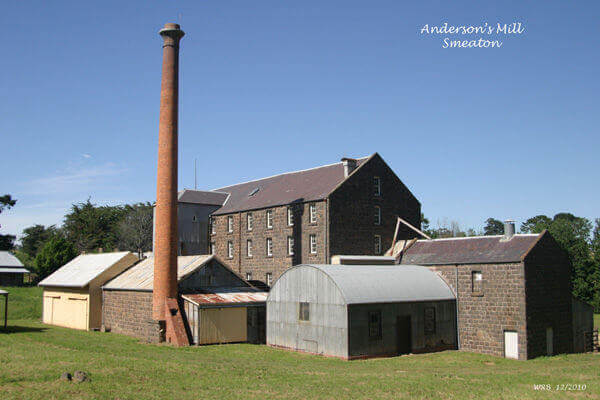

There are strong reasons for finding it of interest. We have, for example, been to Smeaton to see the very impressive Anderson Mill, now apparently an important Central Victorian tourism landmark. We encountered and walked along part of the Anderson tramway when we were doing the Goldfields walk. When I was writing the blog about this I uncovered many parts of the Anderson story new to me, and it came home, as they say, that Sarah was the great-great-great-grandmother of our children. And now here is her journal, or at least extracts from it … a real discovery.

It is written in a tight flattened cursive script which presents difficulties for most people who didn’t learn to write accompanied by an inkwell. So I suggested I’d type it out.

I was absorbed as I typed. Dates right. Events right. Emigrant Scots make new lives for themselves in the colonies through skill, ambition, persistence and hard work. I also thought this is not a story you hear much these days.

But here it is. It is well worth a read.

* * * * *

A Mother Emigrates to the Colonies: My Journal [by S.K.A.]

Arrival at Corio Bay — reflections of the voyage — my sons’ amusements — thoughts on the past

Praise the lord! We are off the ‘Cairngorm’ and on to terra firma at last. Those 103 days at sea will soon seem as nothing when all my beloved sons are united. In this year of Our Lord 1854, Plymouth to the Colonies is a world away.

Thomas Craig, my youngest, passed the voyage happily, writing beautifully in that diary of his. One wonders how he would have filled his days had not his old church friends in Glasgow given him a little book for the purpose of taking notes on the journey! He is a robust 17 year-old youth, who gave up a good position in the new Glasgow foundry to emigrate.

Robert and David occupied themselves by fishing, reading, assisting Mrs X with her young children, arranging musical entertainments and talking to the crew and emigrant passengers. What tales they have been told … of gold nuggets to be picked up off the streets, black cannibals, strange animals and endless forests filled with venomous serpents … I fear they exaggerate some of these tales to make mischief on their Mother. The Lord will give me strength. At times in the privacy of my cabin, whilst writing my journal, I sought comfort by smoking my pipe. Tobacco is my secret weakness … the Lord have mercy on me.

My sons are high spirited and adventurous, and at times the confinement of the ship proved tiresome. We were fortunate that Captain X was attempting to reach Australia in record time. The boys are so excited and enthusiastic about prospects in the Port Philip District that any feeling of remorse I may have had is overcome. What a joy it will be to have all my sons together again!

More thoughts on the Past —

It was a wrench leaving my beloved Scotland, land of my birth. I had resided at New Cumnock, Ayrshire for half a century. However, after dear William’s passing, it was not too harrowing to sell our farm ‘Penclo’. Why the sins of the fathers should be visited on their sons I’ll not know.

With all our industry and integrity we could not clear the inherited debts. I brought the account book of the sheep sales with me. My sons will be delighted to see the excellent prices fetched.

It is just 17 years since that terrible day when the Lord took our dear William. But I must not dwell on the past. Raising an errant daughter and six lively sons without a Father’s authority has been troublesome. The Lord will surely judge I am but doing my duty.

My sons’ achievements —

I wonder of what account the long hardwon Glasgow education will be to them in the Colonies. Sending them off to St. Giles University with but a bag of oatmeal was indeed rigorous, but they will not improve their station in life without Education. My literacy comforts and consoles me. I have brought Robert’s Veterinarian Certificate with me, John is a cartwright, James a carpenter, William an agricultural labourer, David an engineer and dear Thomas Craig taken from his excellent prospects to emigrate.

We arrive — Corio Bay — First Impressions — July 1854 — Disembarkation

At dawn we have our first glimpse of Point Henry. I search for my dear sons as the ‘Carrington’ [sic] berths and wagons pass by on the muddy roads. ‘Dear Mama! Do come! Do you not ken Wm., John and Jas?’ Thomas Craig calls me to greet these three bearded men. Three long years it is since I said farewell to them. How they have changed! They are lean and sun-burned. James’s wife Katrine Vallance and their Australian-born Mary, my first grandchild, welcome us. What a bonny 3 year-old bairn she is! Give thanks to the Lord, we meet again.

John attends to the unloading of our chattels. My big black trunk should have protected its contents, including my family Bible, from the damp. I do hope the seeds William specifically asked for have not been adversely affected by the sea water. He reports the climate and soil of the Colonies are excellent for horticulture. For my part, I insisted on bringing my own little Baltic pine dressing table from ’Penclo’. It is modest but sturdy and will serve well — a remembrance of home.

We say ‘au revoir’ to our shipboard friends and journey by coach to Collingwood, Melbourne Town. The heavy baggage will follow later. I must admit to being filled with curiosity to see our new residence.

Life in the city — Collingwood‚ gold fever

Suddenly I hear ‘Mama! Mama! Look!’ Thomas Craig points to a group of men carrying picks and shovels, some pushing loaded handcarts. ‘Gold! Gold! We’re going to make our fortune on the diggings!’ we hear one cry. I can see the lust for gold and riches in their eyes. Oh! How will my sons resist Mammon’s tempting? What an air of excitement is all about. Many shops are left unattended as their owners are off to seek a quicker fortune on the diggings.

My sons have established a modest building construction enterprise in Collingwood. We all occupy a wooden dwelling in Smith Street, kindly rented to us by Mr X.

We decide to move

The winter climate is delightful. We do not need to spend much time indoors which is fortunate as our residence is too small. We all hold a round table conference and decided to move to Stoney Rises, Smeaton, where Robert with his wife Maggie have taken up land. Perhaps summer in the hills will be more agreeable. I confess I have cast aside my whalebone stays. They are much too constricting in this colonial heat, and are apt to bring on me a fit of the vapours. Thomas Craig attended the Scots Church on the Sabbath wearing no coat. I prayed God would forgive his lack of decorum in his splendid new Collins St kirk.

Journey to Smeaton

Thomas Craig travelled with me by Cobb and Co. Coach to Ballarat. It cost £1-5-0 each, us departing at 6am, and arriving at Cobb’s Stables by 3 pm. I am still sore from the bumps and jolting from the rough roads, and have a slight chill from being put out at the flooded Bacchus Marsh ford. But I thank God I did not need to walk as do some miserable riff-raff, miners and heathen Chinese. Rumours of new gold strikes abound, as do stories of what really happened at the Eureka uprising in Ballarat last year. Those hot-headed Irish are bound to cause strife.

At Smeaton

Robert and Maggie gave us a great welcome to their modest but comfortable dwelling of some local timber. It has a solid floor and is secure against the rain and wind. He is prospering, having acquired Mr X’s excellent flock of yews [sic] and five breeding doggs [ditto]. Robert’s veterinarian training is of great count. He keeps his own flocks well-attended and breeds excellent wool from the best stock available. His advice is much respected and well paid for by the district farmers. John is having constructed a huge bluestone flour mill on Birch’s Creek. He is diverting water from upstream, to power the stone mill wheels which grind the corn.

Further opportunity — James at Dean

The Good Lord has shewn James that an easily-won golden fortune is not to be his. He came from the Blackwood diggings over the ranges to arrive at Dean in the Bullarook Forest on Christmas Day AD 1855. He speaks highly and enthusiastically of the prospects and urges his brothers to take up land there. He has taken a holding with the remains of his ’Penclo’ inheritance, plus a little gold success, established a home and begs us to hurry there urgently before the good land is all bought up.

Journey’s End — from Smeaton to Dean

The ten-mile journey was agreeable. Robert spared us an excellent team to haul the wagon with my personal effects. And what a forest. For once James was not exaggerating. Trees of a hundred feet and more. Native animals aplenty and colourful exotic birds with strange calls. At times I am homesick for the tuneful blackbird and nightingale. Mr X. has released two pairs of mavis [Scottish mistle thrush], so they may breed too and add tune to the present cacophony. Birds as colourful as these would be seen only within the aviary of a grand house in Scotland.

Much to do — Clearing the forest — sawmills — felling timber — Labour — the railway — locomotives — Barkstead to Dean — the Schoolroom — The Chapel — Farm routine

The big forest about my home ‘Loatta’ is soon cleared. An old Abo indicated this place to mean ‘resting place beside water’, so we have adopted ‘Loatta’ as our property name. At the Dean mill logs are sawn into boards and taken by wagon to Creswick, Allendale, Broomfield, and sometimes Ballarat to build houses or line deep mines. Further away are tall straight forests of messmate, peppermint, whitegum, candlebark, wild cherry and native pine. The valleys afford some fresh streams and abundant springs lined about with all manner of ferns, tree ferns and pretty flowers. The wattles are golden in late winter and spring. What strange seasons these are: at home ‘Penclo’ would now have its first early snow. At Yuletide we prettied the dwelling with green branches, but I miss the holly and pine. William has planted the redwood seeds he got from a miner from California. They are growing apace, as are the Chilean pines, cypress, cedars and the orchard.

Naturally I continue to keep the business transactions accounts as none of the men can spare the time. I try to keep a rein on my sons’ ambitions. Last week we purchased an adjoining allotment. Already some land is sown to oats — after the first harvest we had winter feed enough for our horses, plenty of seed for the new field and a tidy sum from the sale of the remainder. How abundant is the Lord and this soil.

We have no lack of labourers — the gold fever has ebbed, and many family men are satisfied to abide in small cottages with constant employment and good prospects. I see the need for a chapel and schoolhouse. These children will not be growing up to fear the Lord, or know their numbers. I am never idle. Daily I use my knowledge of healing herbs to attend to any sickness or accidents.

A New Scheme

The forest close by has been cleared, but the demand for sawn timber continues. David and Thomas Craig have envisaged a means by which logs and sawn timber may be brought down from the Bullarook Forest and Barkstead to Dean. They hope to apply their engineering skills to a clever scheme to build a timber tramway on which will run a locomotive.

Tragedy strikes

This sad day, the twenty-fifth of January 1858, my youngest son Thomas Craig was suddenly and tragically taken from us. Whilst timber-getting at the Bullarook Forest, he was stricken to the ground by a loose branch from a falling tree. A strong north wind blew the branch away from its expected path, striking him a severe blow on the head. He was pinned to the ground and never regained consciousness. Our sad cortege took him to rest at the new cemetery at Creswick where God willing I will join him when my time comes. So this alien land has claimed my last born whose expectations of it were so high. And him here but four years, and just into his twenty-second year. I am distraught with grief, but I must not question the wisdom of the Lord who gives me comfort and strength.

Construction of the tramway

David and Jas. continue with the construction of the timber tramway. Robert resides at Stoney Rises having just taken up more land in Derby in the Sandhurst District. John’s Smeaton mill is now in full production. As dear Thomas Craig was so enthusiastic about the tramway project, I will honour his memory by attending to its completion as soon as possible.

The Barkstead mill now employs 150 men who have built their homes from timber offcuts. A secular school has been established.

We have seen to the construction of our School Room which stands apart from the main dwelling. It is wooden, 12 ft x 22’ x 10’ and lined with panelboard. Miss X is the very capable governess. The Reverend Kennedy comes from Creswick to instruct the children in the Presbyterian faith. The Church of England clergyman is most tiresome about insisting on preaching his Papist nonsense. The Wesleyans are building a chapel beside the stream on the south. I regret to write that the ungodly spend much time and currency at the public houses — either at Macs, the Dean Hotel, or Mr Lennon’s ‘Comet’ at Bullarook.

Visit by William and family

A recent visit by William and his family created a most agreeable diversion. He told of a call by the itinerant artist William Tibbits whom he engaged to paint a delightful watercolour of his residence. The charge was one guinea. Little Tom, Jack, Joyce and Nat wanted to be drawn into the picture, but were forbidden. Their inclusion would have cost extra. [William Tibbits was renowned for this sort of thing. He left a substantial record of the colony’s newly built environment. Here he is at left.]

My Portrait

I have been persuaded to sit to have my portrait drawn. Mr Y promises good value. His samples in pastels on grey paper are very effective. I dress in my best black dress and tie my white lace Sunday Bonnet over my fair hair which I severely part in the middle and tightly braid. I decide to wear the pretty cameo brooch from ‘Penclo’ — my last memento of dear home. The picture is to be mounted in an ornamental frame. I wonder what will become of it, but am feeling too tired to really care, and my cough worsens. I pray I will not be judged guilty of the sin of vanity.

Construction of the tramway continues

The two tramway bridges are due to be completed before the winter rains swell the East Moorabool and Werribee Rivers. They are imposing 50’ high structures reinforced to take the weight of the locomotive. The tramline will run the fourteen miles to Dean and the trip with timber to Buggylanding will be 20 miles. Four daily trips are planned in the summer and three in winter. How proud I am of my sons’ skills and yet I worry. This tramway is to cost £50,000 without the bridges. Then too, there are all the locomotives to import as well as parts for repair and maintenance. The saw blades too are brought from Scotland.

Overwhelming tiredness

I feel very tired. It is eleven years since our arrival in the colony. Today, July 12, 1865, I have had excruciating pain in my chest. I will write no more. My sons come to farewell me. I have great cause to be thankful to Him who has guided me through a long and good life. I long to be laid to rest besides Thomas Craig.

* * * * *

And now, a change of tack, and another story about history.

It’s a true story but she didn’t write it.

As I typed I became more and more convinced I wasn’t reading anything written by Sarah Anderson. It wasn’t immediate because I was busy typing. But I started hearing the voice of the writer and it wasn’t hers.

The document consists of excerpts spread over an 11-year period, short excerpts, probably just picking the eyes out of what is referred to as a journal. And, of course, it all chimes pretty much with what we know to be true about the family — a broad picture, just some if not all of the bones, but they are in the right place.

The three boys migrate from Ayrshire in 1851, land in Adelaide and work off their indenture in South Australia, chase gold in Victoria with some fairly modest success, establish a construction business in Collingwood and so on. Yes. Mum and the younger three boys come three years later. The family set up in Central Victoria, build a tramway to help strip most of the useful timber out of the Bullarook Forest, develop a major cereal mill … No question. All present and correct, and worth knowing and finding interesting if you’re a local history buff or a member of the family. That’s what happened.

But she’s been on the ship for 103 days and gets the name wrong? ‘Carrington’ for ‘Cairngorm’? A transcription error no doubt. Easily done. It might be the same with ‘Penclo’ for ‘Pencloe’ where she had lived for 50 years. Although I’m not sure a Scot would make that mistake. Transcription again. And strange to have a first glimpse of Point Henry as notable … I’d be surprised if Point Henry was called Point Henry in 1854, but there now see — I’m wrong. Named after Captain Edwin Whiting’s brig ‘Henry’ which anchored there in 1836. But why would you notice and comment on Point Henry, a very undistinguished protuberance at the entry to Corio Bay? If you lived in Geelong you could well know it, but arriving from Scotland? However, it might have been one of those landmarks that, say, the Captain talked about — you know — That’s when you know you’re really there! — that become indelible in a traveller’s mind. And they exist. I know they exist.

Ducking off to her cabin to spoke her pipe … could have, could well have… sparks the narrative up quite a bit. Colour, in what I must say is a fairly disciplined and bloodless portrait. But just a bit out on the edge. The choice to anonymise the people, X, Y, she has dealings with might be deemed polite or at least politic. Might be a habit. She could have written ‘heathen Chinese’, but I think it is more likely if she wrote anything of the kind she would have used, in keeping with the times, the plural version ‘Chinee’.

But — and this is where my confidence collapsed — she would NOT have written, or said, or thought, ‘An old Abo’. Too clumsy. Too vulgar. Too intimate. (And as if her sons would leave the accounts entirely to her. As if.) It’s not her.

I reread it more closely and became convinced I wasn’t reading a woman’s writing.

Why? There is the absence of affect for a start. This is a middle-aged, formed, woman starting a new life at the other end of the world. Things will NOT go smoothly. She will worry, have setbacks, be troubled, homesick, feel threatened not least by the comic list of Australian stereotypes which is still used to frighten Englishmen. She will feel, if not necessarily talk about her feelings. That would be Scottish. But she will register them, and not in the way that occurs here.

Will she really make a list that goes ‘messmate, peppermint, whitegum, candlebark, wild cherry and native pine’, or note that the school room is ‘12 ft x 22’ x 10’ and lined with panelboard’, or that the two tramway bridges will be ‘imposing 50’ high structures reinforced to take the weight of the locomotive’? No mate. Nah. That’s the sort of thing I’d do. It’s not her.

She will be interested in domestic detail: what you put on the table to eat, what you put on the table to eat on and with, what you wear, where you might buy it, how you spend your time out of the forest, and especially who you are socialising with, and how they’re getting on with each other. Because that’s what life is.

And quite possibly this is all acknowledged somewhere that we don’t know, Like the ‘Journal of Sarah Anderson as recounted, or imagined, by …’. And that’s fine.

When you go back to it with this in mind, you note that it all has that tone of slightly heroic late Victorianism, a masculine textbook style of missing out no fact — it is very dense with information and very tidy, covers all topics — while cross dressing with regular exclamations of piety.

And I think that makes it even more interesting as a version of how somebody, a capable but not gifted writer, thinks a middle-aged Scottish woman in Central Victoria from 1854 until 1865 would describe her life. And he, for it is a he, is wrong.

We’ll have to look elsewhere for that sort of truth. And you know where it might be found? Somewhere in the contents of that capacious filing cabinet. (And I will even hazard a guess where: in the endless correspondence between Florence Anderson and her sister Myrna Charlton.)