In early August 1945, atomic bombs were dropped first on Hiroshima and then three days later on Nagasaki. This is a precise replica of ‘Fat Man’, the second bomb. The dark colour is a compound designed to seal the seams of the outer shell.

There were several reasons why Nagasaki was included in the list of target cities. One was its location as a major port and as an industrial centre for Mitsubishi where ships, military equipment and armaments were produced, employing 90 percent of the city’s workforce. Another was, unlike most Japanese cities, it had suffered very little damage to this point in the war so it would be possible to quite precisely estimate the bomb’s impact. It could play its role in a scientific experiment.

Kokura (in the upper red rectangle), on the other edge of Kyushu, was the initial target. But heavy cloud coupled with black smoke from burning coal tar lit precisely to obscure the site from enemy bombers meant there was limited capacity for visual identification. The plane carrying the bomb was handicapped by an inoperative fuel pump which meant there was no access to 2,400 litres of the petrol it was carrying. It flew on to Nagasaki where the same weather conditions prevailed but, just as returning to base became essential, there was an opening in the cloud, the weapon was armed, the electrical safety plugs were removed, the bomb doors released and Fat Man, one of three such, was dropped targeted on a tennis court in the mid-reaches of the Urakami valley four or five kilometres from the centre of town.

One presumes it hit the tennis court although the impact of the destabilisation of the 4.85 kilograms of plutonium it contained was felt equally at the two primary schools and cathedral close at hand. Two of the Mitsubishi plants were destroyed along with those working in them, who included 4,000 Korean slave labourers. One count has 39,000 dead immediately, then within 12 months perhaps 70,000.

It might be pointed out that in one night the fire bombing of Tokyo by the allies killed 135,000, and that that fire bombing continued over weeks. It might also be pointed out that Russia’s choice to enter this war was the most likely impetus for Japan to surrender.

Historian Martin Sherwin suggests that there is a consensus among students of this aspect of the war: ‘The [deployment of the] Nagasaki bomb was gratuitous at best and genocidal at worst’.

There are others who think that, regardless of the real reasons, the bombings in combination provided a suitable public scrim for the Japanese capitulation.

• • • • • • •

Of course being in Nagasaki we went to the Atomic Bomb Museum. Of course. There are things you must see there because, in the circumstances, they must be confronted.

The Hypocentre the day after the bombing. The blast was visible from the air 180 kms away. Although most things within a radius of 1.6 kms were completely destroyed (severe impact was noted 4-5 kms away), the stanchions holding up the wires for the electric trains are somehow standing; a factory’s chimneys remain upright in the background. A tumble of bloated bodies can be identified. But the really weird thing is that people are walking around with their clipboards having no idea of the continuing presence of danger. This is a bomb unlike others; there is so much of its impact you can’t see.

The bomb doors opened at precisely 11am.

At the same time one of the support aircraft dropped three packages of instruments designed to measure the bomb’s impact. Each package contained a letter to Professor Ryokichi Sagane, a physicist who had studied at Berkeley and had been a colleague of three of the scientists responsible for the development of the bomb. The letter urged him to tell the public about the danger of these weapons. They were found and passed to Sagane a month later.

I find that both strange and plangent. What is that? An attempt at expiation?

As indicated by the clock, the bomb exploded at 11.02.

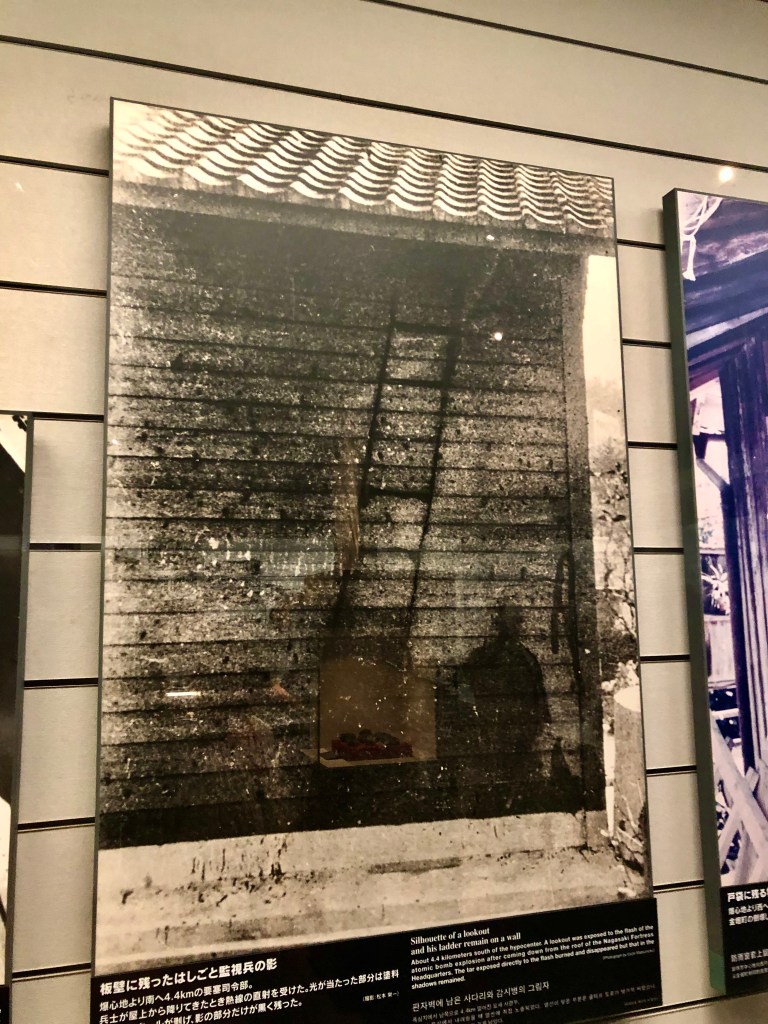

I had read about this at Hiroshima, but this seems like a definitive illustration. The bomb blast 4.4 kms away has disintegrated the watchman, who has just climbed down from the roof, and his ladder. But their ‘shadows’ are left.

These ‘objects’ have been between the bomb’s flash and the wall and have left their imprint not as flesh or substance but as something more akin to a photographic image.

These shadows along with victims moving with flesh dripping off them are two of the frequently commented phenomena associated with the bomb’s impact.

But how much better to have died like this rather than to have lingered on with radiation sickness for months, years — immobilised, suppurating wounds, ulcerated skin, constant diarrhoea and vomiting, permanent headaches.

• • • • • • •

I left moved, but not as much as I might have been and not, I think, in the direction intended. We had been to Hiroshima before and had had the very dramatic experience of listening face-to-face to the testimony of a survivor. ‘We left’, I concluded that blog, ‘chastened’. I didn’t feel chastened this time. The meaning had shifted focus.

It’s not even about ‘atomic bombs’ any more; it’s about ‘nuclear armaments’. Russia, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, China, India, Pakistan, Israel and North Korea possess over 12,000 nuclear weapons almost all of which are vastly more powerful than the bombs that were dropped in 1945. And when I say vastly more powerful, the Russians have tested ‘Tsar Bomba’ which was 4,200 times more powerful. Glass shattered in windows 780 kms distant as a result of its blast which was visibly evidenced more than 1000 kms away. All buildings in a town, Severny, 60 kms away were destroyed. Atmospheric changes were recorded in New Zealand.

Have we become inured to these issues, or do we manage them by ignoring them?

What was front of mind for me after the visit to the Museum was not the nuclear threat, but the increasing fecklessness of leaders oblivious to the medium and long term consequences of their actions and the cheapness of their motives. I was thinking of the results in Ukraine, the Sudan, Gaza, Lebanon and elsewhere. We can kill the leaders of Hezbollah with three American-made and -provided 8000lb bombs. Why worry about nuclear arms? We can revel in the impact of conventional weapons which have become so much more sophisticated and deadly what does ‘conventional’ even mean? Worrying about nuclear weapons suddenly seemed so very last century.

It might also be me getting older and suffering fatigue at the record of humanity’s infamies. But my worst suspicion is that we need another cataclysm, a catastrophe of the highest order, to revise this behaviour, to rekindle something like fellow feeling and civil behaviour on anything but a local level. The ‘rules-based order’ that emerged after the last world war — including the current ‘Rules of War’, the Geneva Convention for International Humanitarian Law, now broken casually and mendaciously daily — was born from a clear memory of its horrors and the equally clear realisation that no one wins a war. No one. There is no glory, no honour, no triumph in the consequences of fighting, not for the vanquished and not for the victors. Wars never leave resolution behind. The ‘lesson’ the enemy is taught is to hate their opponent, perhaps more covertly but with just as much passion. And the consequences, so widely visible today, are the collapse of empathy, of generosity of spirit, of curiosity about and tolerance of others.

‘Lest we forget’, we say every 25th of April. I’m afraid we’ve already forgotten.

• • • • • • •

In the documentary The Fog of War, former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara recalls General Curtis LeMay, who relayed the Presidential order to drop nuclear bombs on Japan, saying: “‘If we’d lost the war, we’d all have been prosecuted as war criminals.” And I think he’s right. He, and I’d say I, were behaving as war criminals. LeMay recognized that what he was doing would be thought immoral if his side had lost. But what makes it immoral if you lose and not immoral if you win?’

Pingback: Nagasaki and Dejima | mcraeblog

Thanks for this reflection, David. It is the reaction others have had to their confrontation of extreme tragedy, too appalling, horrible to face, to contemplate. It’s strongly present in the poetry of the Great War. (Sassoon., Owen etc). These men experienced such horror and inhumanity that they were transformed, never the same, enveloped by the pity of war. And it makes us want others to share the experience, the horror and the insight. (What this generation needs is a good war or a depression!) I’ve just been reading about sparagmos and omophagia in the Greek tragedies . Hippolytus came to mind. The theory of tragedy. The killing, the dismemberment and eating of animals or people. It lurks beneath the liturgy of The Lord’s supper. You might like to check out these terms and see where they lead you in discovering what these myths and rituals are about. There you go. No other reply to your post will be quite like mine, I suggest. The truth is, we need to talk about such stuff sometime. Thanks. Baxter

Edith and Baxter Holly13 Kent CourtEast Doncaster *Victoria.**Australia*

baxterholly@bigpond.com baxterholly@bigpond.com

edithhelen051@gmail.com edithhelen051@gmail.com

Home: 0398419244 Baxter: 0412036843 Edith: 0413132222

David, you should try to watch a film called ‘Touch’, a Japanese/Icelandic film set in London. It explores the long term effects of the Hiroshima bomb on the people of that city. It’s also a wonderful film anyway.