‘NDP’? ‘National Day Parade’ which will occur on August 9th. This is May 24. You will never convict Singapore of being underprepared, not for an event like this anyway. I am standing just above where the Prime Minister and his associated dignitaries will sit. In time the white expanse will fill with spectacles. (In the background, the three towers with a boat on top, is the Marina Bay Sands.)

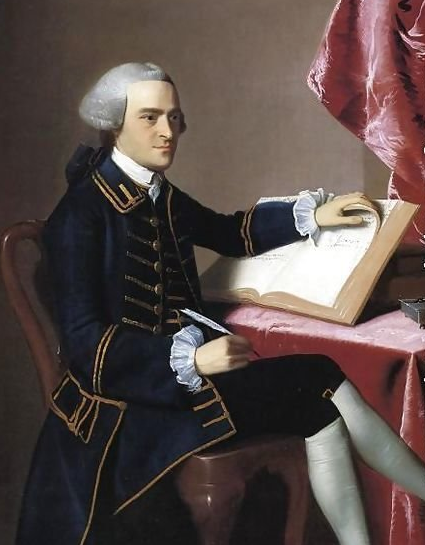

It is special this year because it is the 100th anniversary of Lee Kuan Yew’s birth. LKY: First Prime Minister 1959-1990, ‘Minister Mentor’ of Singapore (the fist behind the throne?) from 2004-2011 and still a member of parliament when he died in 2015. Some political history. Has any leader lasted that long — 56 years — in and around the nucleus of power in a country that gives democracy quite a good go?

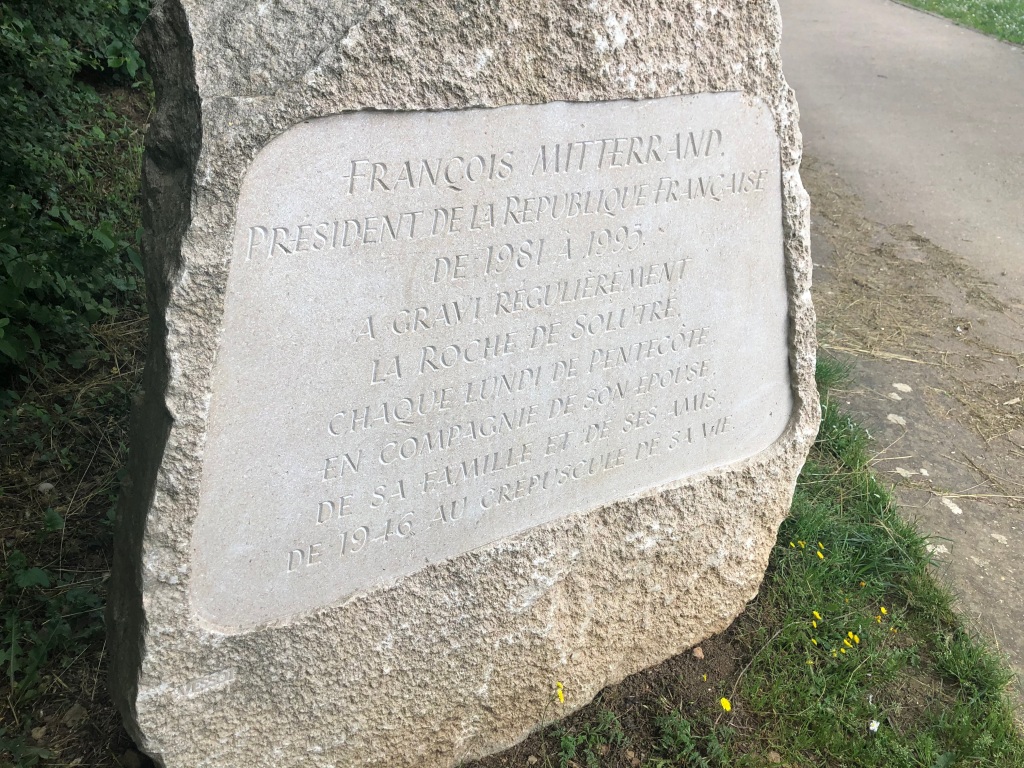

We watched him break down in tears as he announced that, yes, Singapore really was leaving Malaysia. The Parliament of Malaysia had voted quite decisively, 126–0, in favor of a constitutional amendment to expel Singapore from the federation. ‘For me, it is a moment of anguish. All my life, my whole adult life, I have believed in merger and unity of the two territories.’ And then he asked the television cameras to be turned off and because it was 1965 (on the 9th August), and perhaps because it was LKY asking, they did.

He must have been left wondering just what on earth was going to happen to his country. It had an important and busy port, but no natural resources, no capacity to feed itself, issues with water supply and no obvious prospects.

• • • • • • • •

We were in the National Museum and absorbed by the story of Singapore it told. It had always had a port and been important for that reason having a commanding position in the Malacca Straits, the main shipping route between China and India. But over the centuries the source of its governance had wavered: Indonesian (which of course was not Indonesian but most commonly Sumatran or Javan), Siamese and other groups from the north, not always Malayans who appear to have only settled their peninsula a matter of several hundred years ago and have often not been the dominant group. And Chinese. There is strong evidence that Singapore, or Temasek as it has been known for very much longer, is the oldest known Chinese settlement outside of China.

In the early 17th century it got caught up in the wars between the Portuguese and the Sultan of Malacca and was utterly destroyed, ‘sinking into obscurity for two centuries’ as one history has it.

When Stamford Raffles displayed interest in 1819, the port had a population of just a few hundred and the whole island less than 1000. He was interested because it would provide a deep water port with fresh water and supplies of timber for refurbishment of British vessels seeking to increase their leverage over the Dutch as well as providing a haven from pirates on this major trade route. Raffles had a proposition which — coupled with a number of events which included kidnapping and bribery, standard colonial fare really — induced Sultan Hussein to grant the British the right to establish a trading post on Singapore (together with an annual payment to him of £5000).

And, an intimation of things to come, Raffles decided that, to increase usage and to undercut Dutch trade restrictions, the port should be duty free. Over the subsequent decades it became a busy entrepôt, a port where a cargo could be purchased and trans-shipped to another destination — and above all, a place where business could be done.

And, for the National Museum, this is really where the story begins.

Raffles, who has a rather grand statue in front of what is now the Victoria Theatre among many other forms of recognition including the eponymous hotel, was only there for six months. William Farquhar took over. His portrait in the museum suggests a rather stiff Scotsman wearing a uniform which would be impossibly unsuitable for a tropical climate.

Farquhar probably had a difficult row to hoe because one standard gambit in colonialism is intervene, establish military supervision, then forget. He was left with very little income from acceptable sources and so sold licenses for gambling and the sale of opium and turned a blind eye to the commerce in the slavery which was taking hold. The conventional view is that during his tenure things went bad. Raffles returned three years later for an inspection and was disgusted. He drafted a set of new policies for the settlement, which included the banning of slavery, closure of gambling dens, the prohibition of carrying of weapons, and taxing what he considered to be social vices such as drunkenness and opium-smoking. He also laid out a plan for the physical development of the colony.

That’s one line of thinking. More contemporary evaluations suggest that it was Farquhar who built the foundations and Raffles was just a noisy show pony with better connections in England. Regardless, Farquhar was dismissed and his place taken by John Crawfurd who, it really could be argued, did all the hard bullocking work. It was he who negotiated and signed the Treaty which gave the British access to the whole island.

In a region that howled ‘Merdeka, merdeka, merdeka’, independence, independence, independence, not so long ago, I was taken by the near affectionate prominence given to the British and their 150 years of control in the Museum’s display. LKY was educated at Cambridge, and it might be important that the largely Singaporean actors in the film ‘Crazy Rich Asians’ have British accents.

There were Chinese living here before the British became formally involved, but immigration driven somewhat ironically by the Opium Wars increased their number quite rapidly. By 1870 Singapore’s population had reached nearly 100,000, more than half of them Chinese.

Jump. It’s after WW II. The Japanese have come and gone, senior partners in the process of knocking things about terribly. The colony’s infrastructure has been devastated. But a common enemy has helped to cement a sense of unity among the disparate Singaporean ethnic groups. Trade through the port has slowed to a crawl. Tin and rubber are keeping a very patchy economy afloat.

Jump. It’s 1963. Despite worries about internal security and ‘the communist threat’, political independence from Britain has been granted. Next question: should Singapore become a part of Malaysia, already an amalgam of a number of states? Various parties had their reasons. The British thought that this would be a more likely bulwark against the communists (who had recently become more prominent in Singapore). Singapore’s politicians, those in favour — including LKY, a very committed advocate — thought that there would be economic and political advantages in being part of a larger country. The dominant Malayan party, UMNO, thought that this would mean that the Chinese influence in Singapore could be offset.

A referendum is held in Singapore. An option to vote ‘No’ is not included on the ballot paper. Nearly 30% of the returns are left blank in protest and almost all the remainder vote for Option A which is to join Malaysia but with full autonomy, the most arm’s length of the options. Joining was not a popular move.

Jump. But not far. It’s 15 months later and the Malaysian Government has just passed Article 153 of the Constitution of Malaysia, still operative, which provides for ‘safeguard[ing] the special position of Malays’ and goes on to specify and establish in law ways to do this, such as establishing quotas for entry into the civil service, and discriminatory access to public scholarships and public education. Although in the last few centuries the Bumiputra (‘sons of the soil’) have always been the largest racial segment of the Malaysian population (about 65%), their economic position has tended to be comparatively precarious. Thirteen years after the establishment of the constitution and the discrimination in their favour, they controlled only 4% of the economy, with much of the rest being held by Chinese and foreign interests.

LKY was furious about the passing of Article 153: ‘The Malay have the right as Malaysian citizens to go up to the level of training and education that the more competitive societies, the non-Malay society, has produced. That is what must be done, isn’t it? Not to feed them with this obscurantist doctrine that all they have got to do is to get Malay rights for the few special Malays and their problem has been resolved.‘

Jump. Only a few months later. There have been race riots in Singapore. People have died. There is uncertainty among some senior Singaporean politicians about the benefits of remaining in the federation. The Malaysian Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman decides that Singapore must be expelled. The Malaysian Parliament votes. 126-0.

At the time Singapore’s unemployment rate is hovering round 12-15%. There is a housing crisis, the education system is a mess, lack of sanitation creates rolling outbreaks of serious diseases, a predatory Indonesia threatens intervention … no wonder LKY wept during the announcement.

What to do? Encourage foreign investment with tax breaks, build industrial parks, establish the world’s largest suite of oil refineries, the busiest port, one of the busiest airports, deregulate the labour market, engage the Israeli army to help build a fighting force, crack down on public and private misbehaviour (no drugs, or chewing gum, in Singapore). In short become a poster child for the theories of Hayek, Friedman and other proponents of runaway capitalism.

But with a proviso … with massive state intervention. The largely ethnic Chinese government knew what it wanted and set about getting it.

Public housing was built like crazy, a strong reliable and competitive education system was developed, a sophisticated and up-to-date post-school training apparatus was put in place, there was almost uncircumscribed expenditure on infrastructure. (Try the subways! Credit card check on and off.) Cleanliness was instituted as a heavily promoted public good. A lot of work was been put into encouraging you, countryman and visitor alike, to behave in a way which is generally thoughtful and considerate of others. (Current population: 5.454m, 75% ethnic Chinese.)

Paternalism? Sure. But the product is stable, secure and, in some instances, simply and obviously awash with money.

The Marina Bay Sands

Luxuriate in the ultimate lifestyle with unparalleled views and unforgettable experiences.

Revel in unparalleled views at Singapore’s luxury hotel and lifestyle destination. Newest Room Collection. Access to Infinity Pool. World-Class Dining. Luxury Shopping. A landmark of modern sophistication, Marina Bay Sands is Asia’s most iconic destination for chic city-stays. We bring the world’s best entertainment, culture, food, nightlife and experiences right to your door.

The project is more than the sum of its buildings, it is an entirely new urban sector of Singapore, a vital district that is connected with nature, interactive, of a human scale, and climatically sustainable. The seamlessness of indoor and outdoor public space is a hallmark of Marina Bay Sands and a major factor in its success. ($S8b is the quoted value.)

Bottom end $729 a night. Top end. Well, toppish end that you can get anywhere near, $2975pn but that of course is with the $100 food voucher. However I can’t even find a price for the Merlion Suites (387 sq m, bigger than most people’s houses), ‘set on the 50th floor and up, offering panoramic views of Gardens by the Bay and the Singapore Strait. Apart from a private butler to heed your every need, your experience includes a bespoke cocktail experience, complimentary massage for two, and a complimentary round-trip limousine ride.’ I just cannot find a price. How do I book?

On its 56 floors, the MBS has 2561 rooms, 230 of which (all of them really) are out of reach of you and I.

On its 57th floor is ‘an expansive and lush 2.5 acre garden skypark which includes gardens, restaurants, a one of a kind infinity edge pool, and a public observation deck, the longest occupiable cantilevered structure in the world’. Here’s the pool. (It will be self-evident perhaps that these are not my photos.)

You might have seen this in action in the closing scenes of the film ‘Crazy Rich Asians’. Entirely appropriate. There’d be some arrangement I imagine to stop you toppling over.

I bow low before the architects and every single person involved in the construction process. Who was it I wonder who had their tools out on the prow of the longest occupiable cantilevered structure in the world when it was under construction? A collection of heroes. You would need more than a head for heights.

I had additional thoughts. Just a couple of things.

Each tower is ‘double-loaded’ by which I think is meant that there are two bits which embrace each other eccentrically about 5/8s of the way up. Each ‘front’ sea-facing tower is heavily curved which means you can’t put lifts in them, so every time you want your butler, they (pronoun neutral) presumably have to come up the other tower and walk briskly across the walkways attached to the atrium to heed your every whim. That would inflate the ‘heeding’ time a bit. But … ppfft … nothing.

However as we approached I did notice that rather like the ‘Endeavour’, as Lieutenant Cook steered it to safety through the shoals of the Great Barrier Reef after it had been holed, the high-flying ship has been fothered (blue arrow). However, running a canvas rig round the hull might be in keeping with the nautical theme. It may possibly have foundered on the reef of unwarranted expectations, or some portions of gold bullion (see ‘Alan’ below) may have slipped and punctured the infinity pool.

There is a public walkway through the atrium at about level 10 and you are able to watch, enviously, all the action below. (How would you cool that area I wonder; it’s more like the interior of a major pyramid than an atrium.) The walkway takes you towards the ‘Shoppes’, and if you want high end anything you’d be able to find it there. PLUS you can pay to have a ride up and down a 75m bath in a sampan.

I got this glimpse as I got out the other side of the atrium and I found myself having a febrile narrative construction experience. (I haven’t mentioned it was very humid.)

So, you pull into the harbour on the cruise ship. Mass-scale limousine service to the atrium of MBS. Dig in at the all-day buffet. Think seriously about the bespoke cocktail experience, but decide to save it for later. Electric cart to nearby Flower Dome (at left). Take selfies in front of the love heart and join the crowd who for some completely unintelligible reason pile gravel on the top of the cactii. (Just … why?) Return to MBS. Lift to heavily cantilivered observation deck. Take in sights. Wet toe. Go to Shoppes and think of buying some Moncler sneakers (below) for $S1875 but for some reason hold off. Laters. Enjoy the bespoke cocktail experience with the all-you-can-eat evening meal. Sleep, exhausted. Take mass-scale limousine service back to the boat, and Bob’s your uncle. You’ve done Singapore.

And so, finally, you can join the customers of Philipp Plein (not ‘plain’, ‘full’) and become as one with them.

Another reason for going to Singapore

A visit to the Orchid House in the Botanical Gardens.

You can click on any of the images below to make them full screen.

Orchids (Orchidaceae) are the second largest family of flowering plants in the world with about 28,000 species. If New Guinea, which has more than 900 endemic species, is included in Australasia, which is geologically and historically reasonable, they emerged from Australasia.

They are distinctive because of the fusing of the male and female parts of the flower (the ‘column’). Either side and below the column all of them have three lateral petals set above three outer petals or sepals. The lower lateral petal is the ‘lip’ modified to provide a platform for insects.

They can grow in cascades.

Or more modestly.

And I love them.

Singapore takes them sufficiently seriously to grow new strains and name them for visiting world leaders. Thus …

And, DAH DAH, just in the last few days … the Albanese.

Alan

Alan drove us from and to Changi airport. He was a brisk and cheerful young man with a pony tail, and extremely well organised. Before we arrived he sent me the entry forms for Singapore to fill out and post (digitally) so that arrival would be as speedy and easy as possible. He sent me directions and photos of exactly where he would meet us. (‘Just in front of Heavenly Wang.’) And there he was. Precisely. He charged a fixed price which I had already paid and was extremely efficient delivering us to our hotel. I asked if he would take us back again.

We mucked him around a bit with our pick up time for departure which he absorbed with equanimity. The only issue was that he had to do another job, but he would be there as close to our agreed time as he could. He arrived exactly on time because the other pickup had not turned up. He had waited the stipulated time, 40 minutes, but no show. He didn’t mind terribly. He’d done his best — advice, texts, photos, directions — plus he’d already been paid. Does that often happen? ‘Sure. These women come to Singapore from other parts of Asia, Pakistan this woman, to make some money — you know what I mean — and their papers are no good, can’t fill out the entry form, want to stay for longer than they’re allowed. They get taken into a back room and who knows when they get out. Maybe three hours, maybe tomorrow. Happens all the time.’

It had been Alan’s 11th trip to the airport that day. ‘Eleven!’ ‘Yeah. That’s what I do. 280 bookings a week. Booking.com.’ ‘Goodness. What sort of company does that? What sort of hours does it make you work?’ ‘It’s my company. I got 50 drivers, but I can’t get them all the time. So I drive seven days a week round the clock. No curfew at Changi.’ ‘It’s your company and you drive seven days a week?’ ‘Yeah, sure. Got to be reliable and my drivers got other jobs. Singapore you make money. So much money here.’

He went on to tell us that (Sir, but this blog does not as a rule recognise bestowed titles) James Dyson, the British inventor of the eponymous vacuum cleaner, had not long ago bought a five-bedroom penthouse — by repute, Singapore’s largest — in Chinatown’s Guoco Tower for $S73m (A Singapore dollar was worth just more than an Australian dollar when we were there.) A couple of months later he had sold it to Leo Kogan of Kogan electronics fame for $S62m dropping considerably more than 10 mill with transaction costs. ‘He didn’t care. It was nothing to him. He already got another little house in Bukit Timah worth more than 50 mill. But why do that? Why throw the money away? They have games these guys to see how much money they can spend. Indonesian rich guys all come here, Widjaja family, Tommy Hamami, they all come. Lot of money going round in Singapore. Do deals you know. Property, finance.’

[Footnote: Before moving to Singapore Dyson was one of Britain’s foremost advocates of Brexit. This was just before exiting Br himself. What’s sauce for the goose may not necessarily be sauce for the gander.]

‘I’ll tell you something. Give you a little tip. This is how they get around the border people. You can move money like this too.’ (Sure. Me and my billionaire friends.) ‘They get gold and melt it down into little pieces, but it’s got to be 99% pure. If it is the metal detectors won’t find it. They don’t react you know. They can’t read it! You know you can put it somewhere on your body and no one will find it.’ So there’s a tip for nothing. Why would you do that? I wanted to know. ‘I don’t know. I’m not one of them. But there’s always advantages in moving money round so no one knows.’ Our non-Booking.com ride was a cash deal.

Before setting up his driving company Alan had been in the Singapore army for 33 years, close to impossible I thought looking at him, and he’d risen up the ranks as far as he could go while maintaining his Malaysian citizenship. He was offered a senior rank but for citizenship reasons had to decline it. ‘My father lived here all his life and kept his Malaysian citizenship too. Now he’s gone back to Malaysia. Just across the strait you know. Not far. But he got old and couldn’t afford to live here.’ How old was he when he retired? ’72.’ And he can afford Malaysia okay? ‘It’s about one quarter, one third, the cost. Still eat well, live well.’ Alan could see a time when he might want to do that too, but that wasn’t the main reason for maintaining his citizenship.

‘I got a precision engineering company. Micro precision. I run it while I’m waiting at the airport. I sit in the car with my computer and do business. At the moment I am negotiating with a Chinese company for them to set up in Malaysia. The US boycott messed up their business. They dropped 80 percent, so they need their stuff to be coming from another country.’ Good heavens could be fitted in here somewhere. ‘You’re negotiating this now?’ ‘Yeah. Found the land. Nearly finished. Happen soon. Good business is quick business. Everyone happy then.’ We had a discussion about the value of precision engineering. Fundamental we agreed. The car wouldn’t go without it.

We got to the airport. Changi’s not that far from downtown and despite it being Friday night the traffic had eased, and we’d got through a lot in a short time. ‘I’ll make a lot of money’, he laughed, and he told us a story about his 10-year old son cheerily fleecing his mates. Too strong? Probably. Doing business with his mates. I’ve forgotten the detail but it was about delaying gratification through the resale of something he had. ‘He make 15 percent! Ten years old! We Chinese you know. We’re good at it.’

I’d had my wallet out to give Alan all the Singaporean cash I had, not much, but he deserved it all. About five minutes after he drove away I realised I’d left it in the car. But then I relaxed. Alan would know what to do with it. Like many of his compatriots he’s extra good with money.