This was a destination, something I really wanted to see. Coatlicue (‘koh-at-lee-kway’), ‘Snake skirt’, or for some people, and this is a whole different rendering, Tonantzin Tlalli Coatlicue ‘Our Mother Earth with the Serpents Skirt’. (In the National Museum of Anthropology.)

It was found in 1790 during excavations of the Templo Mayor in the centre of Mexico City. After some months it was reburied. One view is that that happened because the statue was so horrifying. A second is that the local indigenous people had discovered where she was and had begun leaving votive offerings — this is 270 years after the supposed dis-establishment of their religion and its practices.

Regardless, she is a dramatic creature. She’s hard to photograph because she’s lit from above and leaning quite a long way forward making her even more threatening. 3.5m high. Monster clawed feet with eyes inserted in them, furred legs full of symbols, and then the skirt woven out of very carefully rendered snakes/serpents and fringed with heads and rattles. The snake belt has a skull mounted front and back. The necklace is composed of human hearts and hands. The forearms are raised palms out in a pouncing gesture. At the elbows are ‘monster’ joints, zoomorphised faces with bared teeth. The lengthened breasts and small rolls of flesh on either side of her midriff indicate that she is a mother. And the head may look fierce but in fact she has been recently decapitated. The scalloped ruffle indicates that. Her ‘head’ actually consists of two serpents locking teeth with the tusks which are a consistent feature of Mexican figures. The serpents can mean wisdom but they certainly mean blood.

She is in the round. From the back she is quite similar and just as confronting as she is from the front. But she is in the round in three dimensions. Under the base of the statue is this carving. It could be Tlaltecuhtli, the Earth God or possibly Tlaloc, a more senior figure who includes a long list of matters related to water in his domain.

It is a masterpiece from any point of view, including engineering. It is likely that it was at the upper level of the temple. How did they get it up there? And how did they stand it up after carving the bottom?

Coatlicue is a crucial figure in the Mexican pantheon. She is often described in terms such as Earth Lord, eater of men, dangerous presence, and wise or at least dominant advisor to Huitzilopochtli (‘weatz-lo-poach-lee’), the dominant god, the god of warfare and The Sun. Huitzilopochtli is also Coatlicue‘s son. She was impregnated by a ball of feathers and produced a warrior whose first task was to fight and kill his sister (related to the Moon) and 400 brothers (‘the uncounted stars’).

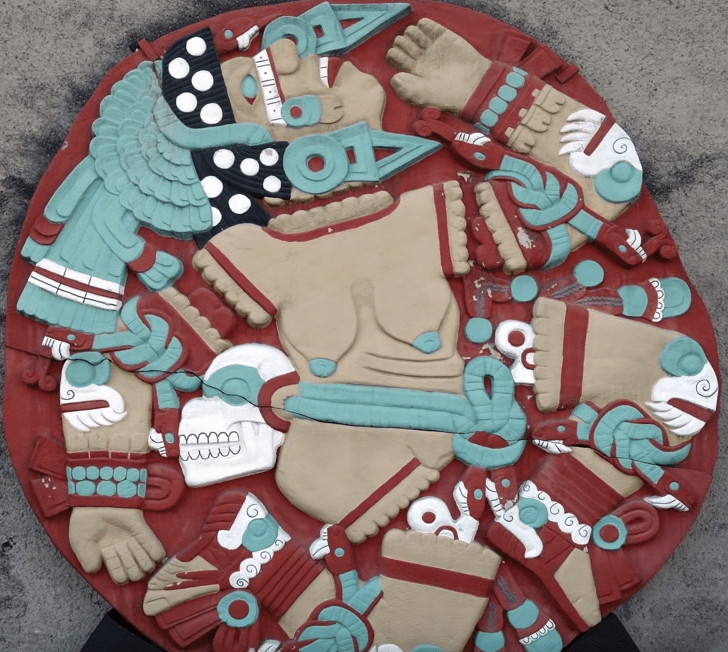

Here are the consequences for his sister, Coyolxuahqui (‘coh-yohl-shaw-kee’), ‘Woman with Bell Cheeks’. At left as she is today in the Templo Mayor Museum. At right is as she may have been, painted and lying in a pool of blood. (Coatlicue would also have once been ablaze with colour.)

The colour makes it easy to see the nature of the dismemberment (find the scallops), the belled cheeks, the monster joints and skull tagged on her belt. She is carved into a large stone disk 3.4m in diameter which was mounted, not once but in five different iterations as the temple was rebuilt and expanded, near the foot of the main steps. It is surmised that one ritual event would be to copy what had happened to her and cast the results down the steps onto this giant medallion.

What was death in this instance? Something quite different to our sense of it. Coatlicue was the recognition of a cycle of generation and decline. In death she was simply reclaiming something that was hers, life extending into death, death a part of life, part of an endless cycle. Life had no higher function than to flow into death. Octavio Paz talks about this: ‘Since their lives did not belong to them, their deaths lacked any personal meaning. The dead disappeared at the end of a certain period, to return to the undifferentiated country of shadows, to be melted into air, the earth, the fire, the animating substances of the universe’. In some moods we might agree.

I was looking at material about this on a Khan tutorial on YouTube. The two presenters talk up the lurid aspects of the statue and its savagery. But then someone has commented: ‘Tonantzin is beautiful. In order to understand the image of Tonantzin Tlalli Coatlicue (‘Our Mother Earth with the Serpents Skirt’) one would have to see it with Mexicas eyes, unlike the ‘Christian serpent’ that represents everything that is evil. To the Mexicas the serpent was as sacred as the eagle. The serpent represented wisdom, because they are the closest to the earth, hence, they adorn her skirts, the open hands along with the hearts represent life, and the skulls death, because she gives life to everyone and takes everyone back when we die. In reality it is a beautiful statue.’ This is the difference between an adherent and an anthropologist.

• • • • • • •

To the visitor, symbols of death — skulls and skeletons especially — abound in Mexico. Ornaments, clothing, cutlery, home decoration, the Lucha Libre, festival puppets, children’s toys, ceramics, confectionary, earrings and endlessly on other types of jewellery. It was impossible not to notice. And art works. We spent an hour or two in the very good art gallery of Mérida and one exhibition was a collection of prints from a recent competition. Print after print was full of skeletons or versions of an imagined — in some cases terrifying, in others more benign — afterlife. This was despite there being no restriction or direction about topic. You just produced what you were inclined to, and this was the widely shared inclination.

So not just skeletons associated with death, but as the inhabitants of a busy urban setting.

And, helpfully bowdlerised by our fellow traveller Anne, this might be some sort of climax. It has to do with Pito Perez, presumably in the background, a popular fictional figure introduced for the first time in the novel, The Useless Life of Pito Perez. He is a classic picaro, a rogue, and this painting may refer to an incident in one of the books. I don’t know. But this would seem to be some sort of apotheosis in the combination of sex and death. No one (but Anne) appeared to be turning a hair.

• • • • • • •

The great celebration in Mexican life is Día de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead. Two days really, November 1 & 2, corresponding with, but by no means the same as, the Roman Catholic commemoration called All Souls’ or All Saints’ Day.

Here’s an explanation from Mexican Sugar Skull, a confectionary company.

Indigenous peoples descending from the Aztec, Huastecos, Zapotecs, Mixtecs, Mixes, Chinantecos, Purépecha, Mexica, Otomi and Mayans were forced to adopt Catholicism and give up their multitheistic religious beliefs. Catholic priests believed they would have more success in converting the Indigenous if they could keep their cultural pagan customs and apply Biblical stories, saint’s names and a monotheistic God to what the people were already believing. Hopes were to convert slowly over several generations and this would create a less combative relationship between the missionaries and the indigenous populations. The indigenous Indian groups all had similar but regionally unique ways to honor their ancestors. They had death rituals, burial ceremonies, beliefs about the afterlife and beliefs that souls could return from the dead at prescribed times to commune with the living. Many Pre-Conquest indigenous traditions called for feasting, building altars, drums & chanting, offerings to the dead and story telling. …

We believe that the gates of heaven are opened at midnight on October 31, and the spirits of all deceased children (angelitos) are allowed to reunite with their families for 24 hours. On November 2, the spirits of the adults come down to enjoy the festivities that are prepared for them.

In most Indian villages, beautiful altars (ofrendas) are made in each home. They are decorated with candles, buckets of flowers (wild marigolds called cempasuchil & bright red cock’s combs) mounds of fruit, peanuts, plates of turkey mole [a rich thick sauce], stacks of tortillas and big Day of the Dead breads called pan de muerto. The altar needs to have lots of food, bottles of soda, hot cocoa and water for the weary spirits. Toys and candies are left for the angelitos, and on Nov. 2, cigarettes and shots of mezcal are offered to the adult spirits. Little folk art skeletons and sugar skulls, purchased at open-air markets, provide the final touches.

Day of the Dead is a very expensive holiday for these self-sufficient, rural based, indigenous families. Many spend over two month’s income to honor their dead relatives. They believe that happy spirits will provide protection, good luck and wisdom to their families. Ofrenda building keeps the family close. On the afternoon of the second day, the festivities are taken to the cemetery. People clean tombs, play cards, listen to the village band and reminisce about their loved ones. Tradition keeps the village close.

Oh to have confectionary companies like that one.

What does Paz say? ‘Everything in the modern world functions as though death doesn’t exist. Nobody takes it into account, it is suppressed everywhere: in political pronouncements, commercial advertising, public morality and popular customs. … The Mexican, in contrast, is familiar with death, jokes about it, caresses it, sleeps with it, celebrates it. True, there is as much fear in his attitude as that of others, but at least death is not hidden away.’

Could be true.

The nearest we came to death in Mexico was, after climbing up the 80 stairs to the Iglesia de Guadalupe at San Cristobal, finding ourselves watching a funeral. I found the music, of which there is a snatch here, most moving.

• • • • • • •

Another thing on my pre-expedition list was the temple of Cholula, the largest pyramid in the world. This is not a natural hill; this is dirt covering a building.

Cholula, the largest pyramid (and temple) in the world, had a Catholic church, the Santuario de la Virgen de Los Remedios on top of it. A very elegant and attractive Catholic church as it happens. There is a metaphor, an obvious one, at work here. This is how it happens: the command position is commandeered. It’s just sort of startlingly obvious here. I have written elsewhere on the topic: if you want to study really effective marketing, you must start with the Roman Catholic Church.

(I’ve just found this pic and have stuck it in for the view of Popocatepetl not available when we were standing on that terrace. It’s for me.)

But the metaphor might be too obvious. The Indigenous peoples of Meso-America were not wiped out and neither were their social and religious constructions. We saw lots of evidence of the syncretism that the confectioners refer to.

This cross is in the middle of the Peubla market. It is Christian, but we do not have a Christ figure hanging off it. The imaging has been modified to reduce the obviousness of human sacrifice as a fundamental part of the introduced religion when it was something that the good Catholics of New Spain were trying to discourage. Instead we have something like a list of symbols, nails, hammer, hands — still rather threatening.

Another reason to notice is because Peubla, a wildly attractive town full of interest is an ‘artificial’ town built by and populated by the Spaniards as a way station for their major trade route between the Mexican Gulf and the Pacific. Spaniards only. What were Indians doing in town? Running the market you’d have to think. Or, if you like, playing a major role.

This church, San Juan Bautista, is just outside San Cristobal at San Juan Chamula.

Chamula is a very particular place. It has a population of about 75,000 and almost all of them are Tzotzil, a variety of Mayan. They also speak Tzotzil, their own language. Pre-Hispanic culture, or an idea of it, has been preserved. Many of the women were wearing shawls and home-made black wool skirts on this very hot day, their hair braided in a particular way, the way of the Tzotzil. And, extraordinarily, it is autonomous, run separately from the regional and national government by members of its own community. Public behavior is managed by men dressed in sheep skin vests holding large wooden sticks.

When we were there the church was awash with flowers, and awash more generally with scrubbing and hosing going on to flush out and replace the pine needles that were covering the floor. At the same time it was decorated, perhaps functioning is the more accurate word, with thousands of lit candles in clumps, but everywhere. Also in clumps on the floor were parishioners mostly gathered round someone, sometimes dressed in white with a mirror hanging from their neck which I believe suggests access to another world. These people had taken control and were conducting their own highly individual ritual ceremonies.

The small groups were chanting, sometimes whistling, oblivious of each other. The key figures are apparently referred to as shamans not clerics, or not clerics as we know them. There appears to be a role for live chickens to absorb evil spirits and also the consumption of fizzy drinks which make you burp to rid you of the same sort of thing, and pox (‘posh’) a fierce alcoholic spirit which would influence your perception and mood.

The walls are covered with images and statues of recognisable Catholic Christian figures, although pre-eminence is reserved for John the Baptist, not Jesus. Nonetheless the church has been decommissioned or ex-communicated or whatever the word might be by the official Catholic Church.

The vibe walking back down the main street to our bus was palpable. Chamula offers tours of itself to make money out of tourism. Don’t go; you mightn’t come back.

And then there was Santa Maria Tonantzintla on the fringes of Puebla. This is the church Aldous Huxley once described as the most unique church in the Christian world. (Reputedly. Would Aldous Huxley have said ‘most unique’? Nah.)

It’s a knockout. Exquisite. Overwhelming. Plain enough on the outside (except for the topiary birdhouse on the left as you enter), you go in … KAZANG! Full tilt Mexican Baroque.

It is built on the site of a temple to a Nahuatl princess. This might have had some impact, who knows? Val told us the story, and I think it goes that a group of artists from Tonantzintla contributed to the decoration of the Puebla cathedral. They did such a good job that when they asked if they could decorate their own church approval was granted. So we have a beguiling phantasmagoria of black, brown, multicoloured as well as white golden-haired cupids, celebrations of corn and flowers, birds and jaguars, black disciples and several thousand characters completely unrecognisable in the Christian firmament. These are not my photos because no photos were allowed. If they were they would show the whole building festooned with fresh flowers and smelling like heaven must.

• • • • • • •

‘Serial Delights’, a bit of a wrap up is next.

Pingback: VEGETAL MATTERS: Mexico | mcraeblog

A fascinating insight into interesting and curious aspects of Mexican culture.