A cenote is a sinkhole, a natural hole just here in limestone, sometimes very deep, which exposes the water table. There are a number of tourist-level ones on the Yucatan Peninsula where (if you’re our travelling companion Caro) photos like this can be produced.

You can imagine the durability of their cultural significance in a land mass so hit-and-miss with water that one of the four foundation Mexica (Aztec) gods was Tlaloc (and there was an equally important Mayan equivalent: Chaac), lord of celestial waters, lightning flashes and hail, and patron of land workers. His main purpose was to send rain after the dry months to nourish the corn plantings, and it is almost impossible to say how important that was. Tlaloc, perhaps punching a bit above his weight looking at that pot, married Xochiquetzal (Quetzal Flower) the goddess of fertility, sexuality and youth.

He had his own ‘earthly paradise’ (as opposed to the celestial paradises in operation) where Mexica who died from one of the following illnesses or incidents would meet and live with the family of water-related deities: drowning, lightning strike, dropsy, leprosy, scabies, gout, generalised aches and pains, and people with stunted growth who were physically similar to Tlaloc’s divine helpers. This narrative is interesting not least for the list of defined ailments. Mexica: Good. Different. So sophisticated in some ways.

Digression: I thought a lot about water in Mexico. Mexicans drink only bottled water, mainly from 20 litre garrofons, the sort of thing you’re supposed to stand around at work, but from little bottles as well. They buy around 28 billion litres annually spending $US15.9b to do so. The cost of 1,000 litres from the tap (mostly but not always non-potable without treatment) is about $US2; the same amount of water, sold in bottles, costs between $US450-650. The bottled water is mainly artesian. The water table is declining, a process which climate change may hasten. 90m plastic bottles are disposed of annually.

And they drink Coke. Bottom rows, 5-litre bottles for just over 3 Australian dollars.

We’re back: The focus is this cenote, Chichen Itza’s Cenote Sagrado sometimes referred to as the ‘Well of Sacrifice’.

It doesn’t look like much here but it is of enormous cultural significance to Mayan peoples.

Chichen Itza is the largest complex of Mayan buildings discovered to date. It is in the middle of the north of the Yucatan Peninsula and dates from 600-900AD. It covers 30 or 40 square kilometers and has an absolute host of buildings including 5 or 6 major temples, an observatory, a market square, domestic buildings, and a colonnade several hundred metres long.

These buildings are of many different architectural styles suggesting the cosmopolitan nature of Mayan society at its peak. Many surfaces are covered in detailed carvings. Hard to imagine, but they would have all have been painted, mainly red, green, blue and purple.

It also has a massive pelota court (160 x 70m), its sides covered with quasi-realistic figures as well as symbolic narratives. Pelota is one of those fascinating oddities (to us) of Meso-American life. Played with a rubbery ball a bit bigger than a grapefruit, you could only use your elbows, thighs and buttocks to move it with the apparent object of getting it through rings mounted at variable heights in the air, here about 6m.

And it might have been if you lost, you really did lose.

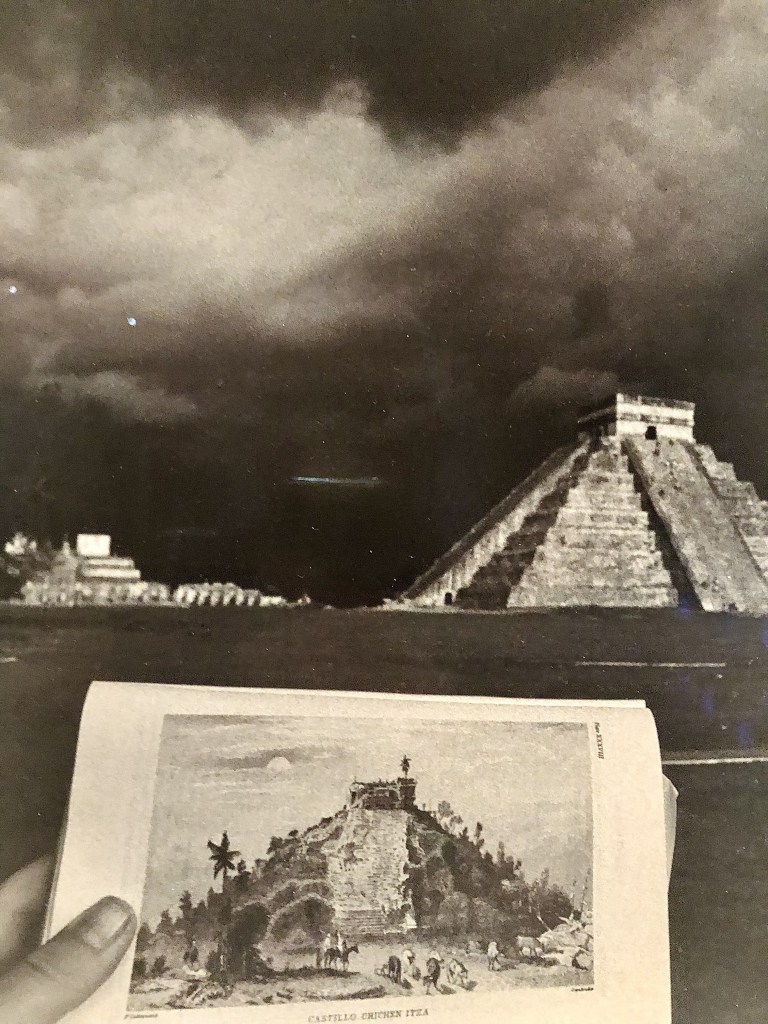

But what the hundreds of thousands, the millions, come to see is this, the Temple of Kukulcán, the ‘feathered serpent’ prominent in many Meso-American mythologies, or, post-Cortesian, El Castillo.

It was almost certainly built over the top of another pyramidal temple. In addition, in 1990, it was determined that both were built over a cenote, which would thus be in the middle of a straight line north-south axis with the Cenote Sagrada, about 500m from the core of the temple, and another less important cenote, Xtoloc (‘iguana’) about 350m away, powerfully amplifying the significance of each. Maya and Mexica alike attached enormous gravity and import to the cardinal directions.

Although its political significance had diminished, there were still Mayans living at Chichen Itza (just as there are today) when the Spanish arrived in the Yucatan in 1526. The Cenote Sagrada was still of high order religious significance. Its status remained stable for centuries after that. Perhaps until influencers decided to use it as a backdrop.

When, after several failed attempts, the Spanish eventually conquered the Yucatan this area became a cattle ranch albeit called Cuidad Real, Royal City. But over time it was reclaimed by the jungle. In 1843 John Lloyd Stevens, an American, by profession a diplomat and by inclination an explorer, published a book with illustrations by Frederick Catherwood called Incidents of Travel in Yucatan, an account of his explorations of Mayan culture. It excited considerable public interest. Could such a building actually exist readers wondered? (This photo will be explained further below, but Catherwood’s illustration is in the foreground being held.)

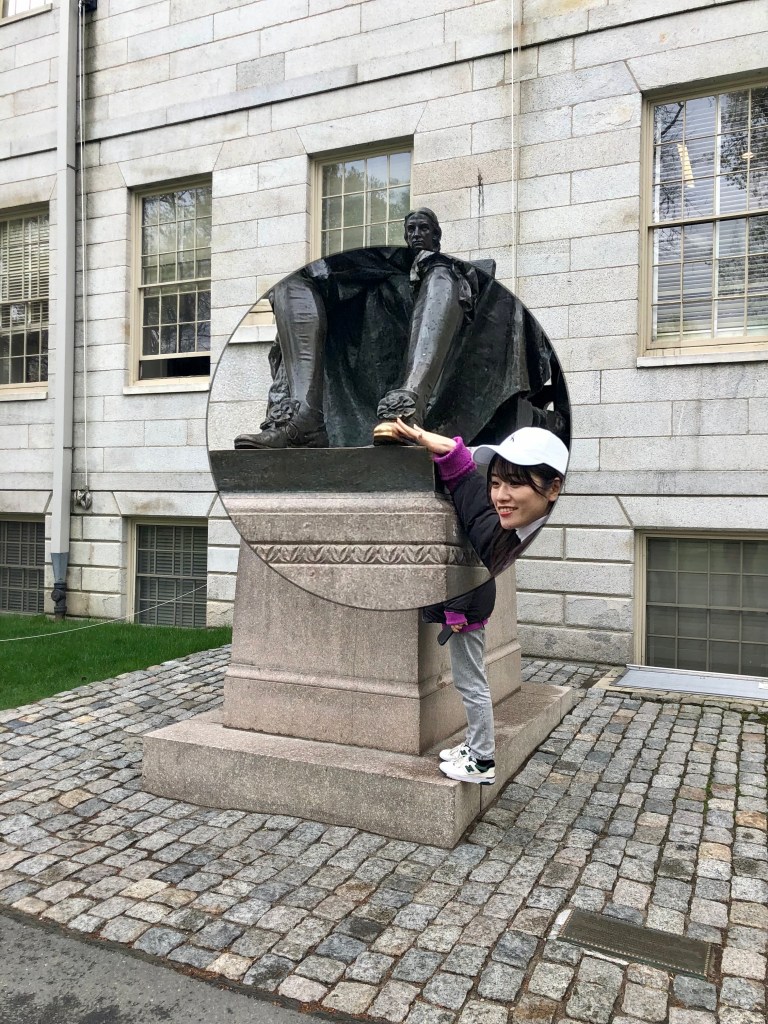

In 1894 the United States Consul to Yucatán, Edward Thompson, purchased the Hacienda Chichén, which included the ruins of Chichen Itza. He explored his ‘property’ avidly and with the interests and sensitivities of his time. He is best known, however, for dredging the Cenote Sagrado over a period of six years. He recovered artifacts of gold, copper and carved jade, as well as the first-ever examples of what were believed to be pre-Columbian Mayan cloth and wooden weapons. He also found a number of skeletons and human bones indicating that this had been an arena of human sacrifice. Thompson shipped the bulk of the artifacts to the Peabody Museum at Harvard University.

This story is only partly about the religious significance of water. It is also about co-incidence and the little epiphanies which occur when you travel.

From Cancun we travelled to New York City. The central mission was to go to MOMA to look at its collection of seminal modern art. But the crowds were thick, thick beyond compare really, and everything looked promising so we decided to go to a side exhibition called ‘Chosen Memories’ just to get out of the ruck. It was all wonderful but two contributions stuck out.

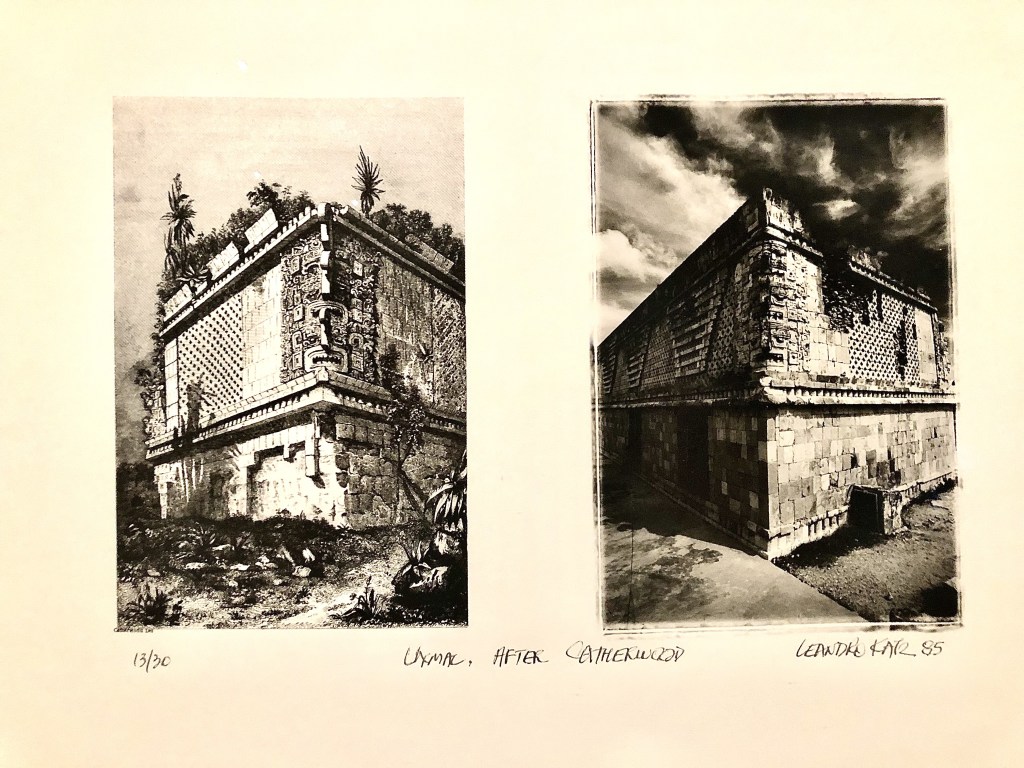

The first was series of lithos by an Argentinian, Leandro Katz, revisiting and reconstructing Catherwood’s illustrations, to make comparisons over time but also to try to provide visual commentary on the way Catherwood may have romanticised what he was seeing. The photo above is one of those lithographs.

It was a how about that! moment. Engrossing.

This is another one suggesting that Catherwood was not far off the mark. Catherwood at the left, Katz on the right.

And following, just in a slightly different direction, putting myself in the story …

But then there was a second contribution by Gala Porras-Kim, a Columbian artist focused on this, a very careful rendering in pencil she had made of all the pieces of textile (including the museum’s centimetre reference marks) which Thompson had dredged from the Cenote and donated to the Peabody Museum.

It was a multi-faceted work which included a copy of a letter she had sent to Jane Pickering, the Director of the Peabody. Part of it reads:

… I am interested in objects suspended from their original function by being stored and displayed in institutions solely as historical objects. In this case, these votive offerings were submerged as tributes to the Mayan rain god Chaac, and probably never meant to leave the cenote. It is clear from the documents regarding the provenance of these objects that human laws were used to displace them from their intended place to their current location at the Peabody. Their owner, the rain, is still around.

Some of the objects had been preserved over centuries because they were submerged in water in the cenote. Their current state of dehydration, caused by their extraction and maintenance by conservators, permanently changed their composition so now they are just dust particles held together through conservation methods. The Peabody is, in fact, preserving this dust as a shell of its past shape. Your storage, being in one of the driest environments in which they can exist, is in complete opposition to their submerged wet state.

The museum is tasked with caring for the object, but should not be limited only to the physical conservation of material form, by extending this care to the immaterial and preservation of the ritual function — the dignitary interests — that still may exist within the object. Since we can only speculate on what the rain might want, we can, by extension, consider ways in which we can reinstitute the ritual life they continue to have within them as well.

[Offering a discussion of possible ideas for restitution]

… Thank you again (etc.)

Two days later we could be in the Peabody (in the suburbs of Boston) and I looked forward to checking signs of increased reverence to ritual function.

There were many signs of ritual function as we walked up through Harvard.

The Peabody is really the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology with a particular focus on the Americas. It is ‘one of the oldest, largest, and most prolific university natural history museums in the world’. (‘Self praise is no recommendation.’ B. Findlay’s mother.)

It specialises in paleontology and had skeletons of big things. But I was more interested in how it treated the First Peoples of Meso-America and their artefacts. Had it learnt its lesson and repatriated materials to their natural homes?

It had certainly learnt some lessons in the arena and, perhaps of course, was a model of political rectitude. Notices everywhere explained and apologised, well justified really, justified and explained, not that they had much to apologise for, and nothing that I could write to Gala Porras-Kim or the curators at MOMA about. Models of a temple, a copy of a statue, couple of other bits and pieces, a terrific Day of the Dead altar,

and a water colour copy of a Guatamalan mural suggesting that gossip existed well before The Modern Era.

My favourites turned out to be a Lakota dance head dress and the Penobscot canoe.

We moved on quite quickly to the Museum of Natural History next door and found a truly weird and wonderful collection of glass flowers. All glass. All. Every single bit.

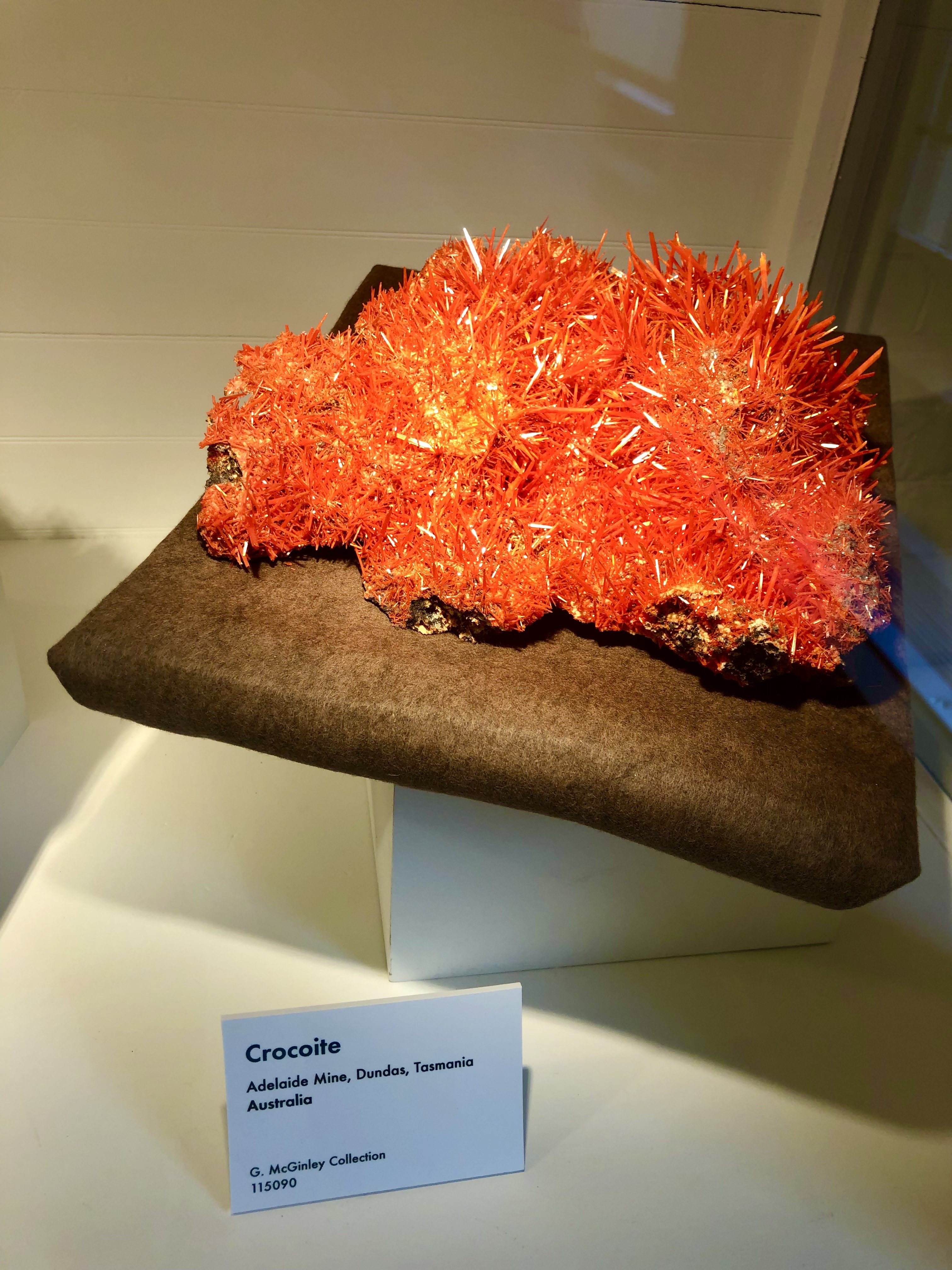

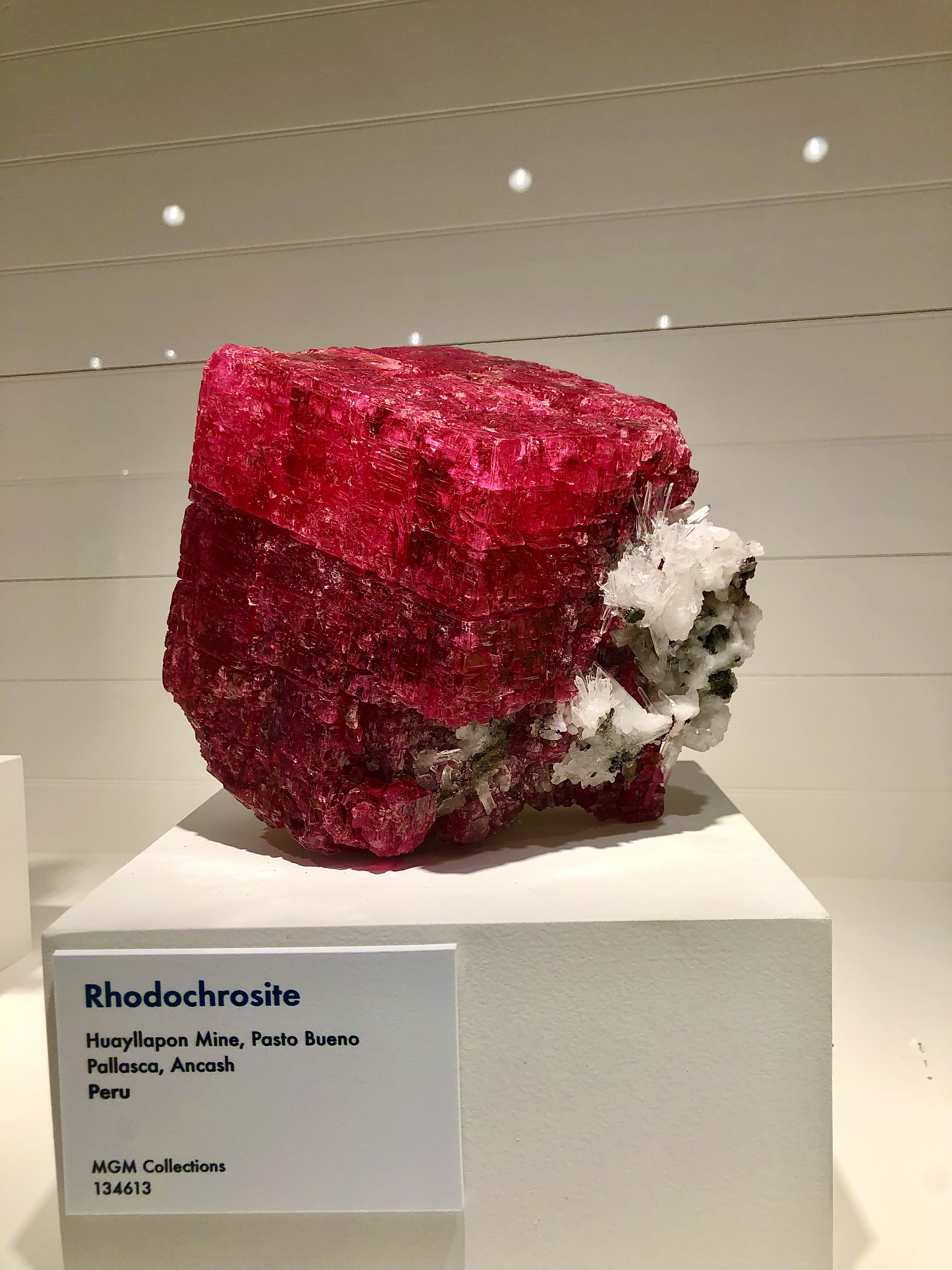

And minerals. OH those minerals!

Is that full circle? … Hmmm. No. Oh well. True stories can lack a narrative arc. Quite strong linearity though. We have at least got to America, for a time the home of revolution. But first, art. The 10 Best Paintings in the World. Phoooot, … just imagine.